by Randall S. Frederick

We might feel, by now, like what I have been discussing here is a simple matter of dividing one’s life and experiences up into compartments. In the bathroom, we confront our real and often ugly selves. We are alone with the stink of who we are. But the porch, well, those are our neighbors. The living room, we might be tempted to believe are people we share cultural activities — TV shows, movies, fandoms. Living room people are safe. Ah, but at the table we begin to see who people really are and it’s a bit more challenging. Maybe we don’t invite them over for weekly dinner, but sure. We’ll have a slice of cake with them at the office, sip a soda, or whatever. At the table, we can still talk to them, even feel the inner pull of having to withhold our own views on things in the name of peace.

I mean something a little more complex than that. When I say there are people I won’t break bread with, I mean we’ve begun to discuss who is “in” with us and who is “out.” I still feel anxiety about the way Jesus embodies a practice of allowing people into our lives, especially “bad” people who we think are entirely wicked or beneath us. In fairness, I feel a similar anxiety about even welcoming good people into my home as well. Does that make me more or less judgemental and discriminatory?

A year and a half ago, I noticed that a mutual friend lived nearby. Those of you on social media will understand this. A friend-of-a-friend kept coming up online, the social media platform kept insisting we become friends. So we did. We commented on each other’s posts a bit. It turned out, we were both heavy thinkers who avoided the prattle of superficiality. One rainy Fall evening, we decided to meet up and see what could be done about becoming “real” friends in “real” life.

It went well. We were all on our best behavior. Lizzie, my wife, made the appropriate number of teasing jokes about me. The mutual friend’s husband did the same. And we all promised to do this again sometime when the weather was a little better. Only that never happened. We went our separate ways and life got away from us. About six months later, we still couldn’t schedule another dinner outing together with all four of us. Or even two of us. Lizzie and I went to Paris and, as it happens, so did they, but in different months. We went to the West Coast and so did they, but again, at different times. Our schedules never aligned and, like many thirty-to-forty-somethings, we remain “friends” online only.

Of course, we replay scenes like this, don’t we? Did they not like me? Did I give off a strange vibe, laugh too hard at a joke, say something off-putting? Questions like these are not new to me and I suspect are not new to you either. Dating is a constant game of questions, for instance. And what was all of this, all of these little steps, if not a kind of dating pattern to meet up and see if we were compatible as real-life friends? I tend to over-analyze things, my wife (and mother, and father, and close friends, even coworkers) tell me. But this one I didn’t.

You see, we had just come out of the pandemic. While everyone at the table was vaccinated and healthy, showing no signs of illness, we were like so many other millions, indeed billions, of people still trying to negotiate this new reality. We chatted. We shared stories. But there was a dim awareness, at least I felt this to be the case, that we had not verbally processed what we were coming out of. The pandemic still felt stressful, even though it was unofficially “over.” Being the iconoclast, yes. I went there. I asked how they were doing, how their kids were doing, how they had fared during the pandemic. It’s a story that has been shared billions, even trillions of times now as each of us share our stories. Yet, even though the story is now familiar to us, at the time, it likely felt overwhelming and profoundly personal. “How did you spend the year or so, tucked away avoiding people and reorienting your life?” gives way to questions about how your marriage was impacted, who you lost, whose political beliefs and conspiratorial thoughts gave way to a divide in your relationships, the births and deaths experienced in seclusion, whether you learned how to make bread and achieved that dream of yours or whether you, like so many, cried yourself to sleep and came to terms with how lonely you felt.

There are conversations that might feel too heavy without the comfort of food. Slowing down, having our mouths full, forces us to listen and listen intentionally to what someone is actually saying instead of merely waiting for them to breathe so that we can offer our own opinions.

Of course, at the table is not the only place where these sorts of conversations happen. The kitchen, with our families and legacies, also reveals who we are to us, to ourselves. Here, as with the table, we can have a drink and loosen up, we can hold space together with another person… to avoid the churning within. Naturally, these conversations are more difficult within the enclosed space of family because we can’t escape their gaze, the way they can recognize intonations. Is that just me? Over decades, we learn to navigate these conversations more carefully because there are consequences. How I discuss my views on gun control or educational reform depends on who is in the audience. It is ironic, I suppose, that I am somehow more myself when I am in a room full of strangers than I am with my family, when I do not have to reconcile accounts with those who know every trick and tick and smirk and blink the way my family does.

Is that just me, I wonder?

Pattie, my mother-in-law is cut from a different cloth. For her, meals are about entertaining and hosting and engaging with them so that they can enjoy themselves. An introvert with a stark pessimistic streak, this goes against who I am. It feels a bit light. When I am sitting at a table with people — and this is not healthy, I imagine — I want to continually stop them and ask them what they meant. What the shift in tone meant, what the subtext to their words might have been, what silent communication was telegraphed when a couple glanced at one another. A good time for me is peeling the flesh off someone’s bones, hearing how they tick, rummaging around inside their heads and hearts to get the full story from them. I have an uncanny ability to make people cry as a result. Most people are so unaccustomed to having someone see them, truly see them, and take note of the intonations in their voice. It’s unusual, I admit, to turn such intensity on someone. In contrast, Pattie’s dinner parties are an opportunity to avoid all of that. Guests can keep things light and airy, they can simply have fun without having to overthink — at least, so long as I’m not at the party also.

Some things are easier to discuss without consequences and context. That is, I’ve been to parties with Pattie where she is more free, more light, more attentive, dare I say “more herself” because she is not responsible for the feelings and thoughts of the entire family. When she is with us, with the entire family that is, there are things that are not available for conversation. She will talk about things up to a point and no further. But when the table is less familiar, it is less complicated. She tells those same stories in a different way. It’s a trick I know well.

As an enneagram five, I have to resist the urge to scream, to slam my hand on the table and demand something more from these conversations. As a Gemini though, there are times when I feel like I understand Pattie thoroughly. Both Pattie and her daughter, my wife, have said that I am “the only one in the family who ‘gets’” her. The table pulls us to know one another, to share of ourselves — but not too much. There are still limits here, but I press people further than that. Unconsciously, I am continually pressing people to open up until there is a transparency known only among family. Even then, I keep pressing until I’m told to stop. I’m not sure where this comes from, but I imagine it’s because my mother’s family was so secretive about so many things. I’d rather people be themselves without feeling the need to hide.

My mother made a decision almost a decade ago to stop talking to her sisters. There had been this unhealthy dynamic between them for over a decade, all the secrets and lies swirling around unacknowledged between them. After the death of their father, my mother made one last attempt to talk to her siblings about how they had grown up, to acknowledge those things and admit how abusive their family dynamic had been.

Her sisters met her with silence and dismissal. It was not surprising. Silence was all they had known. Failing to tell the truth, failing to even acknowledge that the truth existed, had become their last remaining bond.

My mother had been asking for clarity and honesty and respect for decades at that point, but her family, our family, my family, lived within a conspiracy of silence that is familiar to many of you.

Host of the popular YouTube Channel “Abuela’s Kitchen”, Silvia Salas-Sanchez and her abuela (grandmother), Maria Rico Contreras. Illustrations by Niege Borges. Source: Women’s Health.

The Kitchen

Growing up in the South, I was raised with a dozen recipes that are so well-known that I feel them more than make them. My hands flex and loosen, arms reaching for another spice that my eyes do not need to measure. I move by senses unexplainable. A dash of this, a pinch of that, rolled and folded into itself, boiled, broiled, baked, ’til ready. The flavor remains consistent over time with practice.

The legacy of our parents and their parents, our ancestors and predecessors, lives on through us. Their folkways remain in what we cook and how we eat. Whenever I cook, I am mindful of this, or at least I will catch myself measuring a flavor against the standard of my family’s recipes and folkways. I will study my grandmother’s recipes, her shaky handwriting, to make sure any change I make remains aligned with her original intent. For someone else, they do the same thing with the law. What did the framers of the Constitution mean when they wrote these words? Artists will replicate masterpieces, stroke by stroke, to feel what an artist felt to see the colors change before them. For someone else, recognizing the folkways of their ancestors takes another form.

A cousin of mine wears bowties not because he’s especially fond of them, but because that’s what his father did. Whenever I wear a specific belt in my closet, I remember that my father once wore it. My wife learned to write Thank You notes because her mother taught her to do so, just like her mother taught her, and so on to some untraceable point where writing Thank You notes became “just the way things are done.” Every time my wife writes a note, it is a sacred practice. She thinks of her mother and grandmother, remembering the past even as she writes into the future. One of my siblings has an altar in their home, filled with photographs and trinkets of memorial. Each morning, they intentionally pause before this altar to remind themselves of those who came before. Pictures and mementos, collected there, form a sacred place to express gratitude to those who came before and to reflect on the ways in which they continue to inspire.

In the kitchen, recognizing my ancestors is more than simply using grandma’s recipes. It’s richer and fuller, more about carrying something forward than the half-spoon of vanilla I am measuring carefully. The recipe itself is meaningless to me, even the food itself, except for how it produces an experience and elicits a sigh of pleasure. The actions and activities — pinches and dashes — are a kind of ritual, a re-enactment of a tradition that can be found in the lives of someone else in a hundred other ways. The bowties and Thank You notes and altars all point to this next stage of the inner life, where we acknowledge and often confront what came before.

The African-American Church experience. Image from “The Black Church” on PBS.

When I attended an African-American church many years ago, ministers would often talk about breaking ancestral curses and welcoming ancestral blessings. At first, I wasn’t sure how I felt about all that. Growing up in a white, conservative Evangelical home, I probably was resistant to that kind of preaching because, well, what did White conservatives need to apologize for? Somewhere along the way, the words of those teachings began to speak to me. I began to recognize my family, my ancestors, had done some really wicked things. I never really stopped thinking about those words, ancestral curses and blessings. It felt like something White people didn’t want to discuss. When I later began consulting with churches, I kept feeling resistance to the idea whenever I brought it up. It seemed like Black people were far more open to the idea, more receptive, to the realm of the spirit in terms of discussing ancestors and legacies.

When I was in college, in two very different circumstances, both of my parents felt the need to unburden themselves by confessing every terrible thing they had done. It was unhealthy, looking back, but at the time I think they both wanted me to forgive them for the things they had done. The ways they had hurt me and harmed me, the ways they had failed me. Perhaps you have had conversations like these with your own family members, where they overshare in an attempt to find absolution and peace. I don’t think it was entirely selfish. I think, knowing them as I do, that they wanted me to know that I would make mistakes of my own too. I would do things that I would come to regret, like they had. If I wasn’t intentional about doing good to others, then I would hurt people close to me and do seemingly unforgivable things to those who weren’t. I would repeat the mistakes my parents had made decades earlier if I wasn’t careful. Like many parents, they wanted me to learn from their mistakes; the only way I could learn was if I knew what the mistakes they had made were and came to understand why they had made them.

It’s not all peaceful work, moving through the interior of the mind and heart and, ultimately, acknowledging what we have inherited from our ancestors. It can be disturbing. There are, yes, many blessings to be found by looking to previous generations. But there are, if we are honest, some things that need to be acknowledged and changed. Patterns of behavior, ideas that we accept as traditional, behaviors and patterns that need to be exposed as abusive. Some of us choose to deny and suppress our family’s past, to insist that certain things never happened. In my own family, there are many (many) things my aunts and cousins will never admit to and I understand why that is hard for them. At some point though, if we truly want to change and be free of those curses — because yes, that is what they are — we are going to have to admit what happened and call things by their right names. This is the only way to fully access generational blessings, I believe.

We began to see this happening all across America with the Black Lives Matter Movement and the dozen other causes aimed at getting us to recognize our complicity in evil, the ways we as a nation continue to perpetuate evil every day. Confrontational at times, consoling at others, the hope was that we might make a different decision and — to borrow the expression of the churches I once attended — “break the generational curse.”

Many of us began to confront systemic racism, inherited violence, the attitudes and folkways and customs with which we grew up. We began to reconsider many of the things we had been taught, particularly those things handed down to us from our parents and their parents. We began to recognize slowly and then all at once that dad’s fascination with guns was a little strange. When so many children were being shot with automatic weapons, why did he buy another one? And then another? Turns out, it was in preparation for “the uprising,” when he and other “real Americans” would overtake the country. Mom’s general level of annoyance when she went shopping and her hair-trigger demands for a manager, it turns out, only happened when she was in the lane with a non-white cashier.

These things change us, they flavor us, you might say. I’m not saying everything we inherit from our folks is okey-dokey as long as we acknowledge it, or that behaviors, patterns, or fixed thinking should be given a pass because people are older and that’s “how they are, you know, sigh.”

Just this morning, an anchor on a news show said something about an intersex author that struck me, yes even me as a hetero and cisgender white male, as a bit condescending. “You know,” my wife countered, “She is part of a different generation.” Part of me recognizes and accepts this, while another longs for a better expression of understanding and reconciliation in public spaces. When someone is vulnerable enough to discuss their genitals on live television before 9 a.m., and how their bodies were surgically changed but their lives were profoundly changed in meaningful ways, maybe they deserve a little more than, “Good for you. Alright! Ah. Well… after the break we’re talking about toaster ovens and which one might be right for you! Stay with us.”

Some things, even well-intentioned, still need to be acknowledged, corrected, and changed. Statements and actions, we know, are not always malicious in their intent but they can still harm people.

In Judaism, the word “sin” is not comparable to the way Christians understand it. Three words are usually translated by Christians as “sin” from Hebrew, but none of them actually mean that the way Christians mean it. When you flip through a Jewish prayer book, you see the word “sin” all the time because it has an adaptable translation. The people who translate Jewish prayer books are usually not trying to sound religious, like Christians. “Sin” may feel right in context, but it’s not a good way to translate these three words.

Chet is usually translated as sin, but it doesn’t mean that. It means ‘to miss the mark,’ or ‘to be off.’ In other words, a mistake. Mistakes are manageable. You learn from mistakes. You don’t learn from sin.

Avaira is also usually translated as sin, but it doesn’t mean that either. It means ‘to transgress’ or ‘to cross a line.’ Cross a line is another type of mistake. You got carried away. You went too far. But again, with reflection and introspection, there is still potential for growth.

Avon is often translated as iniquity, but no one knows what that is exactly. Some understand iniquity as part of who you are, part of your identity. And where do you get your identity? One of the ways we build an identity is through our relationship with (or the absence of it) our families. Typically though, avon/iniquity is understood as some kind of ‘trouble.’ It is a warning, even a warning label of sorts. A label for who? The community, maybe. And because of this, it’s more serious than a simple mistake. It calls out to people before you even enter a room, a warning or threat to them that here comes ‘trouble.’ However, avon/iniquity is not the word for ‘evil.’ Let’s not go too far here! You’re not a debased sinner condemned to the fires of Hell forevermore. Let’s keep things in perspective. You did something wrong. Whatever it was, it’s become part of your identity — how people see you and understand you. Okay. Acknowledge that, reflect on it, grow, make amends, and move on.

Some corners of Christianity emphasize the concept of sin a whole lot. Grouped together, every word, thought, and action is sinful. We live under the cloud of sin, everywhere we go and with everything we do.

This is oppressive. And not at all what the Bible talks about when it discusses “sin.” I’m not inclined to look for a demon behind every lamppost and neither should you. Rather, as C.S. Lewis puts it in Mere Christianity,

I know someone will ask me, ‘Do you really mean, at this time of day, to re-introduce our old friend the devil — hoofs and horns and all?’ Well, what the time of day has to do with it I do not know. And I am not particular about the hoofs and horns. But in other respects my answer is ‘Yes, I do.’ I do not claim to know anything about his personal appearance. If anybody really wants to know him better I would say to that person. ‘Don’t worry. If you really want to, you will. Whether you’ll like it when you do is another question.’

From C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity.

In the Hebrew Scriptures, sin has a social impact. Our actions and behaviors matter and have consequences. By the time of the New Testament, sin had become a private matter between the individual and God almost exclusively, without much consideration of how our actions impact others.

What I am discussing here though is specifically the ways we normalize sin, evil, and malice within our families and points of origin. We take things as “just the way things are” without examining them and, in so doing, give permission to ourselves and our families to cause harm.

In an important part of the Hebrew Scriptures, commonly called the Ten Words (or Ten Commands/Commandments) from Exodus chapter 20, God even admits that evil is visited on people to “the third and fourth generation.” In case anyone missed it, God repeats themself a few chapters later in Exodus 34. For Christians, the thread gets picked up again by the Apostle Paul who writes in Romans chapters 5–7 that from a certain point of view, human sin and death are a corporate problem rather than an individual one. Theologians often go one of two directions with this concept — either sin is so widespread that it is somehow part of human nature, or alternatively (in alignment with Jewish teaching, specifically tikkun olam), each of us have a responsibility to confront evil where we find it and do what we can to change things. Offenses are not just about us, individually, but are the responsibility of everyone. In Judaism, and again with the Jewish concept of tikkun olam, this means that challenging those things we have inherited from our parents is an act of righteousness, or the right way to orient our lives.

In other words, I’m not hung up on seeing evil in one this or that form. Sin, evil, and malice take many forms but we can move past them.

This is very much like the kitchen, isn’t it? We inherit folkways and customs, we observe for years the pinches and dashes, splashes and generous “cups” as a rule of measure. We take things for granted. We contextualize fixed thinking as part of aging and, in a sense, give up on people ever growing past a certain point. We settle into lives, like grandma or our uncle did before us, and that’s that.

Except now, part of a younger age bracket who is still aging, we find ourselves questioning what we have inherited. We feel the tug toward continuing to grow or giving up and settling into dotage. Perhaps we begin to realize there were secrets we missed. Grandma’s pecan pie cannot be replicated according to the recipe she gave us. Some things will die with her if we don’t catch it in time, while others will be carried forward incorrectly. Ah well, we tell ourselves, that’s what it means to be part of this generation.

Yes. In case it needs to be explicit, I am asking you to deconstruct yourself and your family. I am asking you to do the hard work of asking questions about yourself, what you have learned and replicated. Are you of a certain faith because that’s what your parents were or because that is what you are, yourself, unique from them? I am asking you to trace those things you take for granted, those spiritual practices and beliefs, those personality traits and sense of humor. I am asking you to do this not because I want you to pass judgement on anyone, or be iconoclastic and offend your loved ones, but so that you can correctly trace back what has been inherited and decide for yourself what needs to be carried forward.

Conventional spice rack available through SpiceLuxe website.

Let me put this a different way.

In your kitchen cabinet, you likely have a collection of spices. Salt and pepper are a staple. If you live in the South, you probably have a bottle of Tony’s, which is definitely (absolutely) better than New England’s Old Bay (catch me out outside if you say otherwise). Keeping with our theme, let’s think a little deeper than this. What do the spices embody about your life? Variety is the spice of life, they say, and the variety of experiences we have and the variety of our family experiences change who we are. We are not, despite what most of us may wish, tabula rasas into adulthood. We are impacted, flavored even, by what happened to us as well as what happened to those around us. The abuse my mother experienced changed her, which in turn changed how she raised me, which in turn changed me or who I might have been. The spices of my mother, you might say, have changed the way I was made.

How these experiences assemble and make us who we are, creating a unique “flavor profile” so to speak that we call our personality. This is not a light thing, and I do not wish to be flippant or brush past the important details of how we become who we are. Epigenetics, an emerging field in scientific as well as counseling studies, is the study of how your behaviors and environment cause changes that affect the way your genes work. Unlike genetic changes, epigenetic changes are reversible and do not change your DNA sequence, but they can change how your body reads a DNA sequence.

Epigenetics also explains how identical twins can be so remarkably dissimilar. It is neither nature nor nurture, it turns out, but the combination of both as well as an additional component, how we process these experiences. My father and I both grew up in poverty with distant fathers, yet this does not mean we understand poverty in the same way. For my father, poverty compelled him to go into the Navy to secure a future for himself. It compelled me to go to college. There are, as should be obvious, a million little details, a million little granules of salt and sand, that make us different but ask either of us what experience has shaped our lives and we will both say “poverty.”

In the Jewish experience, every Jew today still feels the impact of the Holocaust even when they did not experience it themselves. Seeing grandparents with the numeric stamp of concentration camps changes how people see the world and the possibility of human evil among us. The desecration of synagogues by racists changes how one experiences their religion and, in turn, the expressions of other religions. Though every individual who identifies as Jewish has lived a unique life, there is still a consistent cultural experience that creates a Jewish identity.

It’s not just a Jewish experience, though. Or even our families. The experiences we accumulate over a lifetime, the “spices” that change the flavor of our lives, sometimes perpetuate cycles of harm. Researcher Rae Johnson in Embodied Activism (2023), writes

Traumatologists are increasingly coming to understand the degree to which trauma (including the complex trauma of oppression) is experienced and held in the body — particularly in the nervous system — and expressed in our embodied relationships and interactions with others. While our relationships are a primal source of human connection, oppressive social systems place a severe strain on those relationships.

At a fundamental level, oppression functions through disconnection — disengaging and separating us from others and from ourselves. And unlike other forms of trauma, the threat of relational rupture due to oppression is not in the past; it is still, and always, in the present. Research into the embodied experience of oppression has identified responses, patterns, and pain points in members of oppressed social groups that closely resemble the symptoms of trauma, including hypervigilance (sense on high alert, always scanning the environment for threats), disturbances in the autonomic nervous system (“revving” too high or too low), somatic disassociation (feeling disconnected from the body), and intrusive body memories (upsetting physical sensations without images or narrative).

Not to leave things in a dismal state, Johnson is quick to add

Although our bodies can be co-opted, hijacked, and colonized by the forces of domination and control, they are also crucial, and often untapped, sources of knowledge, creativity, and connection… Fortunately, a wealth of emerging scholarship supports just such a stance. Derald Wing Sue, professor emeritus of psychology at Columbia University, has recently published the promising results of research into microinterventions: strategies for undoing, disarming, preventing, and resisting the harmful effects of microaggressions. Trauma models are increasingly focused on healing the embodied impact of oppression and on introducing strategies for cultivating resilience in and through the body. Several neuroscientific studies suggest that introception (the felt awareness of our body) is positively correlated with human empathy, and that both can be nurtured. Stategies have been developed for enlisting our bodies in the effort to enhance our moral courage and resolve conflicts more effectively. In other words, the key ingredients for sustainable social change through embodied relational engagement are already available and waiting to be harnessed.

I’m wondering what kinds of cultural and familiar and relational and experiential flavorings you have and whether you recognize each taste, each flavor, each spice, for what it is. There’s no tidy way to communicate those questions to you, I think. Each of us are so unique, so spectacularly unique, and yet we barely recognize it. We become so accustomed to the recipe of who we are that we begin to lose our own flavor. Even here, in exploring the self, it is easy to shrug off the discussion of the inner life. At times, you’re aware that “an egg smells too much like an egg” because you are sharp, your senses attuned to many things, but you are so accustomed to who you are and how you are that you take yourself and your inner life for granted as though it is flavorless and uninteresting.

Last week, I made chili because it is Fall as I write this. After months of unusually hot weather and an absence of rain which is also unusual for South Louisiana, there was that special weekend where the rain finally came and the weather changed. Every Fall, my wife craves Pumpkin Spice Lattes and I make chili. However, this batch smelled strange to me. My mother says I am very much like her own mother in this way, “You are the only two people I know who say an egg smells too much like an egg.” My wife, meanwhile, had tasted the chili and said it was fine. Not my best, but still really good. She brought some to her sister and our nephew and niece who also loved it. To me, however, the chili didn’t smell right or taste right. It smelled too strong, but — at least for me — had no flavor. I don’t mean it was not as spicy as I like. I mean, I felt the texture but simply didn’t taste anything.

That’s how a lot of us approach our lives, I believe. We’re so accustomed to it that it either smells a little weird, but we’re not sure why or how, or it has no flavor. The people around us are able to note the flavors and spices, coo over how good it is, but to us, it’s flavorless. Perhaps taking things to a granular level, the fine grit of spices, might help you dive a little deeper with your self-exploration.

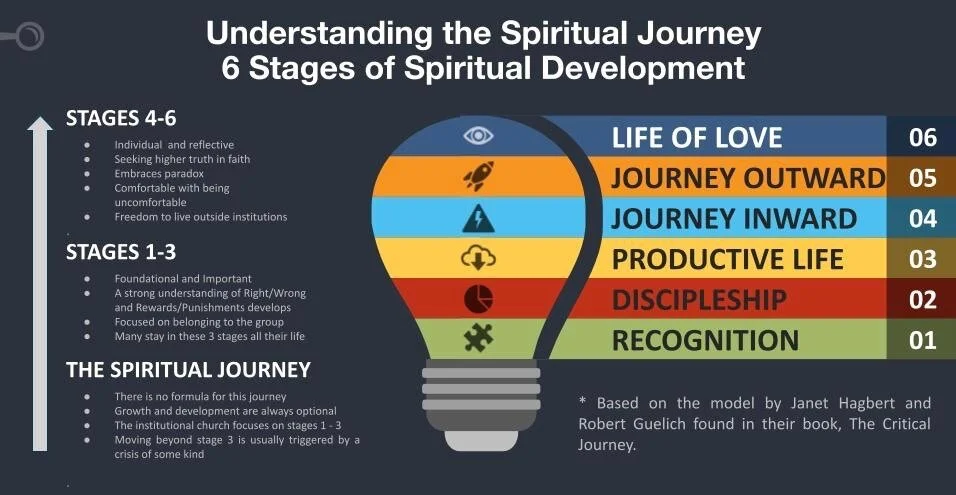

Graphic based on the model by Janet Hagbert and Robert Guelich in their book The Critical Journey.

In their book, The Critical Journey, Janet Hagberg and Robert Guelich provide one model for understanding the spiritual journey. After all, what is self-exploration if not a spiritual journey? The book lays out six stages of spiritual development that we can use to guide our own individual lives. Understanding the stages and determining what stage of the journey you may be in can be helpful.

Stage 1 begins with a spiritual awakening.

Stage 2 is marked by learning and developing basic spiritual disciplines such as prayer, reading scripture, participating in baptism, etc.

Stage 3 is all about ‘doing.’ Taking the practices from stage 2 and beginning to put action to your faith. Identity is found in belonging to the group.

Stage 4 is messy and marked by uncertainty. This stage doesn’t feel like growth as much as it feels like the end. Questions and doubts trigger a crisis of faith, but they lead to a deeper understanding of God with the right help.

Stage 5 is transforming as we surrender to our uncertainty and learn to serve others from our weaknesses. We focus on others with a renewed sense of God’s acceptance.

Stage 6 is a stage that transcends us. Living an abandoned life, we can give up anything for God to help others.

Stages 1–3 of the spiritual journey are more outward-focused. Developing a belief system, spiritual discipline, and a sense of belonging are critical steps that can’t be skipped over. These stages are where the Western Institutional Church tends to focus its energies, which is really a shame. When I was a little boy, I recall every church I attended — it felt like this, anyway — concluded the service with an invitation to “get saved.” Inside of the churches, this meant a dedicated time to either reorient one’s life or, if you were supposedly already saved but doubting this at that time, to rededicate yourself to salvation and this continual reorienting of one’s life.

Even as a child, the frequency of these calls for salvation made me sad. Was this all the spiritual life was, I wondered? Dedicating, rededicating, and then rededicating yourself again to some continual journey? It felt small and hollow to me, even as a child. I wanted to know there was something more than getting saved. I wanted growth. I wanted change. I wanted development.

Getting people saved, discipleship, and building a community for people to belong to are essential steps in spiritual development, don’t misunderstand, but they are only half of the journey. Many people never move beyond stage 3, remaining satisfied. Those who move beyond stage 3 have often had a faith crisis that pushes them to seek answers not found in stages 1 through 3.

Stages 4–6 are inward-focused and individualized and that’s where this book finds you. I trust that you are already at stage 4 as you open these articles.

No two lives are the same, as I have been saying, and therefore, it is nearly impossible to build a program to help large numbers of people navigate their unique crises and the doubts and questions that arise as a result. In spiritual matters, books like these fall into two camps. They are either prescriptivist or descriptivist. The prescriptivist, to hit as many people as possible and sell books, insists on change and “getting your life right.” The descriptivist is a little more difficult, more intentional, and specific. The latter three stages, where this book finds you, require us to get honest with ourselves, deal with our own crap, and face our monsters.

Stage 4 is the stage of deconstruction. Prior answers no longer suffice as deep inner struggles cause life to feel unsettled. Many hit the wall, tempted to give up. Believing change is not possible, they go back each week to rededicate themselves, believing that is all the spiritual life is, continually committing oneself to an undefined and unspecific purpose each week, basically moving furniture around and never making an actual change.

And listen, that’s okay if that’s where you’re at.

Seriously.

I’m not here to suggest you are failing in some way. Rather, I am inviting you to keep going because those who persevere see a new dimension of faith opening up within them. Moving from stage 3 to 4 requires accepting the invitation to experience death — which is scary! — and trusting the promised “resurrection” of renewal, enlightenment, confidence, and self-acceptance on the other side. Getting coaching from those who have gone before is key to successfully navigating the journey and not ending up shipwrecked. Again, I am not judging or minimizing the hard work you have put into your life. I am challenging you to grind your life down, to name the spices, and to see what can be made from the ingredients.