This is not to say that the rational approach of Edwards was superior to the emotionalism of John Wesley, but that Wesley was better able to capitalize on the economies of thought existent at the turn of the century. There were cultural and political divides in America in the latter half of the 18th Century that had nothing to do with religion, but which revivalists were able to benefit from and utilize in their increasingly divisive rhetoric. It is, after all, important to note that both sides of the Civil War prayed to the same God for radically different outcomes, believing that this same God was on their side and not that of their neighbor. We can see that this divide existed since settlers first landed on the new continent, but it is the Great Awakening where we see American religion migrating towards anti-intellectualism. The very foundations of Evangelicalism are contentiously anti-clerical, anti-establishment, and even anti-American if we are to judge the religious energy against that of the Founders who debated, fought, and engaged in diplomacy so that God could be worshipped apart from patriotic fervor and understood in a way more comprehensive than individualistic hunches. In contrast, Evangelical thought even before it began to congeal and formalize was resistant to the vision of the American Founders because it refused any expression that was not self-authenticating, subjective, and intolerant. Intolerant to authority, responsibility, or standard of conduct. The tragedy of American religious discourse is that we must continue to allow Evangelicals a seat at the table when they belong in the stable. The loose, informal, ignorant, misinformed, and misguided antidisestablishmentarianism that so characterizes Evangelicals today has existed in some form for centuries, necessitating a constant and continual revisionist history within as much as an exhausted permissiveness from without. Without agreement on history, operational definitions, or shared understanding of the nature of reality (over subjectivism, folk religion, and the characteristic neglect of structure), Evangelicals are diametrically opposed to rationality and civility. Evangelicals have posed a perpetual concern for religion generally and specifically Christianity in American life together with the advancement of society, and in the interim between each new salvo in their “culture war” of their own orchestration have embodied a consumeristic worldliness and litigious politic directing opposed to the scriptures they claim to revere, specifically denounced by the Savior they claim to worship, and specifically condemned by the epistles that expanded upon in the Pauline, Johannine and Petrine Epistles as well as the Early Church Fathers and the Reformers Martin Luther and John Calvin. Evangelicalism, in light of history, post-Axial religion, and post-Dark Ages philosophy and ethical norms is anathema, a perversion of the faith, theology, and heritage it continues to claim. It is a parasite, a cancer, adaptive enough to remain dormant before a rather unpleasant episode in the form of televangelism, supposed revival, or political destabilization. There is hardly an episode where Evangelicalsm has not profoundly altered a situation for the worse, and it remains even now an abomination whose origins in America can be traced to the anti-intellectual sentiment that Americans once so proudly inherited.

Historian Richard Hofstadter, writing in his 1963 Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, points out that

The American mind was shaped in the mold of early modern Protestantism. Religion was the first arena for American intellectual life, and thus the first arena for an anti-intellectual impulse. Anything that seriously diminished the role of rationality and learning in early American religion would later diminish its role in secular culture. The

feeling that ideas should above all be made to work, the disdain for doctrine and for refinements in ideas, the subordination of men of ideas to men of emotional power or manipulative skill are hardly innovations of the twentieth century; they are inheritances from American Protestantism.

Since some tension between the mind and the heart, between emotion and intellect, is everywhere a persistent feature of Christian experience, it would be a mistake to suggest that there is anything distinctively American in religious anti-intellectualism. Long before America was discovered, the Christian community was perennially divided between those who believed that intellect must have a vital place in religion and those who believed that intellect should be subordinated to emotion, or in effect abandoned at the dictates of emotion. I do not mean to say that in the New World a new or more virulent variety of anti-intellectualist reaction was discovered, but rather that under American conditions the balance between traditional establishments and revivalist or enthusiastic movements drastically shifted in favor of the latter. In consequence, the learned professional clergy suffered a loss of position, and the rational style of religion they found congenial suffered accordingly. At an early stage in its history, America, with its Protestant and dissenting inheritance, became the scene of an unusually keen local variation of this universal historical struggle over the character of religion; and here the forces of enthusiasm and revivalism won their most impressive victories. It is to certain peculiarities of American religious life – above all to its lack of firm institutional establishments hospitable to intellectuals and to the competitive sectarianism of its evangelical denominations – that American anti-intellectualism owes much of its strength and pervasiveness.

These peculiarities were not without attention. Moving into the first half of the 19th Century when rancor was percolating into what would become the Civil War, Nathaniel Hawthorne, the most prolific author of the upper half of the 19th Century, documented in fiction what by then well established. Hawthorne’s most famous works during his lifetime were The Scarlet Letter and Young Goodman Brown, which was a dissection of Puritanical superstition, a somber study of hereditary sin, and a reckoning with the facade of holiness. His audience would have immediately known that of which he spoke, for it was their own inheritance and present experience. The anti-intellectual attitude had become prevalent in American society, manifesting in a legion of ways to crow among the graveyards of thought at various revivals that historians would call The Great Awakening. Hawthorne insisted that Americans meditate on the toll anti-intellectualism had taken since the birth of the nation and, more importantly, their own families. He insisted that his fellow citizens question the origins of their shared nation. More importantly, Hawthorne’s implicit question was whether a nation founded upon suspicion of one’s neighbor, harsh judgment of infractions, and the facade of holiness was a legacy his contemporaries wished to carry forward into a new era of industry.

In a Thanksgiving sermon delivered in 1862, prominent Methodist minister Daniel S. Doggett would denounce writers like Hawthorne and Melville along with historians who wrote objective accounts of history. American history had originated with William Bradford, whose Of Plimouth Plantation was a heavy-handed and far from impartial account of the first settlements. Historians who did not replicate Bradford and build similarly “faithful” accounts ignored the hand of providence and were the truly illiterate. “It has become customary for history to ignore God,” Doggett lamented. “The pride of the human heart is intolerant of God and historians are too obsequious to its dictates They collect and arrange materials, they philosophize upon them, but their philosophy knows not God.” History, the Methodist minister offered, was not only written by the victors but by those who knew God as he did. History was what Evangelicals said it was.

Evangelical preachers emphasized personal salvation and piety more than ritual and tradition; pamphlets and printed sermons crisscrossed the Atlantic, encouraging the revivalists. The success of the Awakening was as much a testament to powerful preaching that gave listeners a sense of deep personal revelation as much as it was a recognized need for salvation by Jesus Christ. Pulling away from ritual and ceremony, the Great Awakening made Christianity intensely personal to the average person by fostering a deep sense of spiritual conviction and redemption, by encouraging introspection and a commitment to a new standard of personal morality. It reached people who were already church members. It changed their rituals, their piety, their very concept of self-awareness. To the evangelical imperatives of Reformation Protestantism, 18th century American Christians added emphases on divine outpourings of the Holy Spirit and conversions that implanted within new believers an intense love for God. Revivals encapsulated those hallmarks and forwarded the newly created Evangelicalism into the early republic.

In his God’s Almost Chosen Peoples: A Religious History of the American Civil War (2010), historian George C. Rable notes that Christians took Doggett’s condemnation of subjective history to heart. They began to take the writing of history away from professionals and tell their own stories, which were now infused with self-reflection and internal perspective. Tellingly, Doggett’s contemporaries

embraced a providential understanding of not only the war but also everyday life. Everything – storms, harvests, illnesses, deaths -unfolded according to God’s will. Popular understandings of how the Almighty shaped the festivities of individuals and nations may not have been profound, but such beliefs were pervasive. Northerners and Southerners, blacks and whites often spoke in remarkably similar ways. References to God’s will filled diaries, letters, conversations, and presumably many people’s thoughts. For some folks, explaining fortune in terms of divine favor or calamities as signs of divine judgment might have been simply customary or habitual, verbal ticks that hardly bespoke deep piety. And those hostile or indifferent to any religious world view hardly thought in such terms. But even taking such people into account, a good number of Americans sincerely believed that the Almighty ruled over affairs large and small. So it was hardly surprising when they saw the anguish of sectional strife and civil war reflecting a providential design.

By the 1790s, Evangelicals in the Church of England remained a small minority but were not without influence. John Newton and Joseph Milner were influential evangelical clerics who networked together through societies such as the Eclectic Society in London and the Elland Society in Yorkshire. The Old Dissenter denominations (the Baptists, Congregationalists and Quakers) were at this time succumbing to evangelical influence and revisionism, the Baptists most affected and Quakers the least. Even today, Baptists cannot seem to agree on their origins except that they have always been there and can be traced to the teachings of Jesus and later Paul. Baptists assert that the apocryphal interim between Paul and today is non-essential since their faith has always remained pure, even as a remnant that sprung forth in God’s providence long enough to denounce the evils of all other forms of Christendom even as it fulfilled their own lineage. Like Athena, Baptists insist they have always sprung forth from the mind of God fully mature and without blemish to set right the perversions of the false interpretations of God and in some sense the clash of interpretation as much as culture explains the Evangelical death drive for the support of war, violence, torture, and exploitation despite being called evils, sins, forbidden, outside the counsel of God, and the worse of offenses by which eternal damnation shall be secured by no less than Moses, David, Isaiah, Ezekiel, Jesus, Peter, John, and Paul. Still, having eyes to see and still not seeing as well as ears to hear and still not hearing, as Richard Niebuhr would put it in his 1957 The Social Sources of Denominationalism, “An intellectually trained and liturgically minded clergy is rejected in favor of lay readers who serve the emotional needs of this religion (i.e., of the untutored and economically disfranchised classes) more ade

quately and who, on the other hand, are not allied by culture and interest with those ruling classes whose superior manner of life is too obviously purchased at the expense of the poor.”

Evangelical ministers expressed dissatisfaction with both Anglicanism and Methodism but still often chose to work within these churches until in the 1790s, all of these evangelical groups, including the Anglicans, were Calvinist in orientation, attempting to wed nationalism with epiphany. Their methods would prove fruitful even as they caused new divisions that were left unaddressed. A century later, Methodism (the “New Dissent”) was the most visible expression of evangelicalism by the end of the 18th century; Wesleyan Methodists boasted around 70,000 members throughout the British Isles in addition to the Calvinistic Methodists in Wales and the Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion organized under George Whitefield’s influence. The Wesleyan Methodists, however, were still nominally affiliated with the Church of England and would not completely separate until 1795, four years after Wesley’s death. The Wesleyan Methodist Church’s Arminianism distinguished it from the other evangelical groups. At the same time, evangelicals were an important faction within the Presbyterian Church of Scotland. Influential ministers included John Erskine, Henry Wellwood Moncrieff and Stevenson Macgill. The church’s General Assembly, however, was controlled by the Moderate Party, and evangelicals were involved in the First and Second Secessions from the national church during the 18th century.

Hofstadter continues,

The style of a church or sect is to a great extent a function of social class, and the forms of worship and religious doctrine congenial to one social group may be uncongenial to another. The possessing classes have usually shown much interest in rationalizing religion and in observing highly developed liturgical forms. The disinherited classes, especially when unlettered, have been more moved by emotional religion; and emotional religion is at times animated by a revolt against the religious style, the liturgy, and the clergy of the upper-class church, which is at the same time a revolt against aristocratic manners and morals. Lower-class religions are likely to have apocalyptic or millennarian outbursts, to stress the validity of inner religious experience against learned and formalized religion, to simplify liturgical forms, and to reject the idea of a learned clergy, sometimes of any professional clergy whatsoever.

America, having attracted in its early days so many of Europe’s disaffected and disinherited, became the ideal country for the prophets of what was then known to its critics as religious “enthusiasm.” The primary impulse in enthusiasm was the feeling of direct personal access to God. Enthusiasts did not commonly dispense with

theological beliefs or with sacraments; but, seeking above all an inner conviction of communion with God, they felt little need either for liturgical expression or for an intellectual foundation for religious conviction. They felt toward intellectual instruments as they did toward esthetic forms: whereas the established churches thought of art and

music as leading the mind upward toward the divine, enthusiasts commonly felt them to be at best intrusions and at worst barriers to the pure and direct action of the heart though an important exception must be made here for the value the Methodists found in hymnody. The enthusiasts reliance on the validity of inward experience always contained within it the threat of an anarchical subjectivism, a total destruction of traditional and external religious authority.

This accounts, in some measure, for the perennial tendency of enthusiastic religion toward sectarian division and subdivision. But enthusiasm did not so much eliminate authority as fragment it; there was always a certain authority which could be won by this or that preacher who had an unusual capacity to evoke the desired feeling of

inner conviction. The authority of enthusiasm, then, tended to be personal and charismatic rather than institutional; the founders of churches which, like the Methodist, had stemmed from an enthusiastic source needed great organizing genius to keep their followers under a single institutional roof. To be sure, the stabler evangelical denominations lent no support to rampant subjectivism. They held that the source of true religious authority was the Bible, properly interpreted. But among the various denominations, conceptions of proper interpretation varied from those that saw a vital role for scholarship and rational expertise down through a range of increasing enthusiasm and anti-intellectualism to the point at which every individual could reach for his Bible and reject the voice of scholarship. After the advent of the higher criticism, the validity of this Biblical individualism became

a matter of life or death for fundamentalists.

This anti-intellectualism lowered the standards enough to allow almost anyone to do the work of God. The Second Great Awakening (which actually began in 1790) was primarily an American revivalist movement that resulted in substantial growth of the Methodist and Baptist churches. Charles Grandison Finney was an important preacher of this period and at the start of the 19th century, Christianity saw an increase in missionary work from Evangelicals who felt compelled to share their vision of hard work and nationalism with other regions of the world. Many of the major missionary societies still in existence today were founded around at this time, though all have polished those origins to claim revelation or divine compulsion rather than uncertainty and the necessity of poverty, migration, and charity among founders. With missionary work, both the Evangelical and high church movements could benefit from the appearance of religiosity and the exporting of the American way of life – hard work, providence, and misery that was occasionally punctured by the miraculous. Those who did not join a missionary society heard a familiar narrative of hardship and could metaphorically baptize their hopes for something greater by giving from their meager share.

In Britain, in addition to stressing the traditional Wesleyan combination of “Bible, cross, conversion, and activism”, the revivalist movement sought a universal appeal, hoping to include rich and poor, urban and rural, and men and women. Special efforts were made to attract children and to generate literature to spread the revivalist message. “Christian conscience” was used by the British Evangelical movement to promote social activism. Evangelicals believed activism in government and the social sphere was an essential method in reaching the goal of eliminating sin in a world drenched in wickedness. The Evangelicals in the Clapham Sect, for example, included figures like William Wilberforce who successfully campaigned for the abolition of slavery.

Not so in the continental United States. Divided by war and still suffering during the Reconstruction, Americans could no longer agree on a vision for their nation. This difference would shift the attention of Evangelicals away from social activism, which had contributed to the abolition of slavery and wiped out the slave trade entirely along the coast, depressing entire industries and reorienting many to new forms of labor. Many Christians, suspicious of Evangelical emotionalism and the smug social gospel of the high churches simply settled for a civil religion that emphasized unity and shared responsibility for the future of the nation. But in the late 19th century, the revivalist Holiness movement, based on the doctrine of “entire sanctification”, took a more extreme form in rural America and Canada, where it ultimately broke away from institutional Methodism. In urban Britain the Holiness message was less exclusive and censorious.

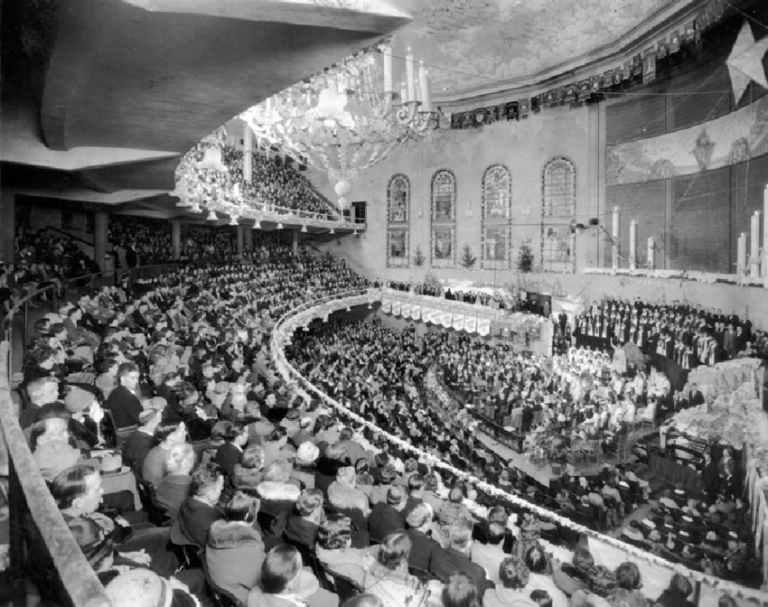

To better contextualize the challenges of the new century, John Nelson Darby of the Plymouth Brethren and an Irish Anglican minister, devised modern dispensationalism, an innovative Protestant theological interpretation of the Bible that found a ready audience among the Evangelicals who quickly incorporated the idea as a doctrine. Here, we might see an effort by Evangelicals to claim a foundational teaching of their own in an effort to break away from the mainline to legitimize their loose choosing of teachings from paternalistic denominations. According to scholar Mark S. Sweetnam, who takes a cultural studies perspective, dispensationalism can be defined in terms of its Evangelicalism, its insistence on the literal interpretation of Scripture, its recognition of stages in God’s dealings with humanity, its expectation of the imminent return of Christ to rapture His saints, and its focus on both apocalypticism and premillennialism. Cyrus Scofield further promoted the influence of dispensationalism through the explanatory notes to his Scofield Reference Bible. Additionally during the 19th century, megachurches, churches with more than 2,000 people began to develop. The first evangelical megachurch, the Metropolitan Tabernacle, a 6000-seat auditorium, was inaugurated in 1861 in London by Charles Spurgeon while Dwight L. Moody founded the Illinois Street Church in Chicago. These new revivalists were making strides to advance Evangelicalism as a rival and distinct challenge to the Reformed Churches.

An advanced theological perspective came from the Princeton theologians who continued to expand and build the idea of Theology as a field of study to bulwark biblical interpretation from the Evangelicals. The Princeton theologians such as Charles Hodge, Archibald Alexander and B.B. Warfield ushered in an intense century of insight and careful explanation, bridging the centuries with a conservative and traditional reading of scripture from the 1850s to the 1920s with systematically theological work and rigorous education in sharp contrast to the cultic communities of Scottish-Australian John Alexander Dowie, dietary restrictions of Presbyterian minister Sylvester Graham, celebrity of Aimee Semple McPhearson, and the Pentecostalism of William J. Seymour, Charles Parham, William Branham, and Smith Wigglesworth.

Pentecostal minister Finis Dakes attempted to copy the work of Scofield by publishing a comprehensive study bible, but when it became public that he had written an extensive amount of the notes in prison, many Evangelicals began to question the morality of their ministers. In 1937, during Dake’s ministry in Zion, he was convicted of violating the Mann Act by wilfully transporting 16-year-old Emma Barelli across the Wisconsin state line “for the purpose of debauchery and other immoral practices.” The May 27, 1936, issue of the Chicago Daily Tribune reported that Dake registered at hotels in Waukegan, Bloomington, and East St. Louis with the girl under the name “Christian Anderson and wife”. With the possibility of a jury trial and subject to penalties of up to 10-year’s imprisonment and a fine of US$10,000, Dake pleaded guilty, and served six months in the House of Corrections in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Though he maintained his innocence of intent, his ordination with the Assemblies of God was revoked and he later joined the Church of God in Cleveland, Tennessee. He eventually became independent of any denomination; it is not known why he later ended his relationship with the Church of God, but this was not an uncommon headline. Aimee Semple McPhearson was discovered to have been divorced and later faked her own kidnapping to explain a tryst in Mexico. Wigglesworth, for his part, claimed to have brought his dead wife back to life long enough to pray with her one last time and Dowie allegedly healed those born with disabilities. As Evangelicals became increasingly militant, their near-neighbors, Pentecostals would continue to face scandals until the end of the Twentieth Century when, over one summer, televangelists Marvin Gorman, Jim Bakker, and Jimmy Swaggart would respectively be exposed for adultery, money laundering, and regularly meeting with prostitutes.

With each of these figures, we see Evangelicals openly defiant of formal religion and willing to engage in “worldly” business practices, litigation, and blatant lying to excuse their behavior, deceive the faithful, and demand money for private jets, mansions, and vacations to say nothing of their disinterest in Civil Rights, social and environmental responsibility, and unquestioning alliances with political figures who promised access to power and material resources.

One thought on “Evangelicals and the Golden Calf, pt. IV”