In 1969, at the insistence of his wife, Jimmy began The Camp Meeting Hour, a half-hour show featuring gospel music and preaching.

After the first month, he was ready to shut it down. It was the refrain of his ministry; what he wanted to do was not what “the Lord” or his wife told him to do. He bucked. He balked. He prayed through. Eventually, he would come around, but unhappily. He was constantly looking for a way out, a way to show God and Frances that he could be his own person and still come out on top. He didn’t like to be handled and managed, his day scheduled and systematized. He was a free mind and spirit who wanted to experience each day, not tick boxes.

He was restless.

Stuck behind a microphone, he wanted to return to the familiar rhythm of being on the road. No one called in, donations were nonexistent. He needed people. Unable to work a room, to feel the energy of a crowd, with only his own voice to listen to felt like a complete waste of time, if not terrifying.

Jimmy was no Billy Graham or Oral Roberts, that was for sure. Graham yelled because there were thousands of people in packed stadiums, the technology still new, and he wanted to be heard. What he had to say was important, after all, a matter of life and death, eternal fate, national interest. Roberts was far more comfortable behind a microphone; he had used them under the tents of his camp meetings to call people forward, to bring them into the experience, to connect with them and have “a point of contact” for their miracle. But Swaggart withered. It was a completely different experience facing the tiny audience of a single microphone. With The Camp Meeting Hour, he had to learn a completely different presentation style. He had to restrain himself. He had to be focused and controlled. He had to follow a script. He couldn’t shout. And if he waved his arms around, that was fine, but no one would be there to see it, to do the same, to give him the instantaneous feedback he had grown accustomed to having. His thunderous voice, belting songs and sermons to the back of auditoriums and theaters had to be suppressed in a soundbooth. There was no crowd to feel, to ride, to laugh with. No one gave him the immediate feedback he needed, the assurance that he was saying the right thing. There was no stage, no performing here. He was alone for the first time.

Desperate for any kind of feedback, Frances urged him to ask listeners outright whether they wanted him to continue or pack it in at the end of that first month. If it wasn’t profitable, if the donations weren’t going to come in, then they needed to hit the road again. As it was, she felt deep in her spirit that if Jimmy could remain patient, an impossible task she admitted, they could have a little more stability. They could reach an even larger audience. Radio opened up new audiences with new potential for new revenue streams. For Frances, it was always about what would be most profitable. Centralizing their ministry and having access to a single studio would help make their expenses more predictable, making it easier to forecast what would come next. Radio seemed like the answer, but not if it proved yet another unnecessary expense. Jimmy could sing, he could preach, he could be everything she knew he could be. And they could sleep in their own beds. He just needed to be patient.

To their mutual surprise, people called the station. Honest in his solicitations, they sent money to keep him on the air. They sent letters to the stations, asking station managers to keep the young preacher on the air. They ordered records and promised to keep listening. A few years later in 1975, Jimmy and Frances would expand to a weekly television program. A decade later, his weekly telecasts reached approximately two million households in the United States, making him the most popular and successful televangelists of the era, even bigger than Billy Graham and Oral Roberts. There was no time left to think and feel things fully anymore, things were moving so quickly.

No, the situation would not get any better. The difficulties would remain. But you see, God saw something that Jimmy Swaggart could not see. In that day so long ago, I could not even begin to remotely see a radio ministry that would touch the hearts and lives of hundreds of thousands of people. I could not even begin to see the millions that would be touched by the television programming that would girdle the globe. I suppose if God had shown it to me in a vision, it would have scared me so badly that possibly it would have hindered my progress with Him, because then those types of things seemed impossible. But of course, with God nothing is impossible.

I think I paid my dues the hard way. My love for the church goes back to nearly twelve years spent in crusades in local churches. I remember the countless nights we would witness the Holy Spirit moving and touching the hearts and lives of so many, as they would come down those aisles and kneel at an altar to find the Lord Jesus Christ as their precious Savior.

I remember the first real breakthrough we had (which was in Alton, Illinois). The meeting lasted some six weeks. Several hundreds of people were saved and filled with the Holy Spirit. I think that one meeting changed my life. It increased my faith, enabling me to believe God for great things. And from then on, the meetings seemed to take on a completely different complexion. Whereas previously they had lasted from one to two weeks in length, suddenly they were going from four—up to nine—weeks in duration. Now I know that sounds almost unheard of nowadays, for a revival meeting to last that long in one church, but the crowds kept coming—the buildings oftentimes packed to capacity—people getting saved, lives being changed. And I think all of this was preparing me for the work God was then calling us to do.

And then the Lord opened up radio. This was in 1969, January 1st. Our first station was in Atlanta, Georgia. If it had not been for the people of the Assembly Tabernacle where Jimmy Mayo pastored, possibly this ministry would not have survived in the way it did. They stood with us in those struggling first days. And then there was Houston, and Hardy Brundage helped us to stay on the air. Then there was Minneapolis, Minnesota. These were the first struggling stations. And then God started to bless it—a moving of the Holy Spirit that swept over my soul that resulted in the program going on over six hundred stations and developing one of the largest radio audiences in the world.

It was during the beginning of the radio ministry (after we had been on the air for possibly two or three years) that the crowds became so large in the churches we could no longer stay there. Then very reluctantly I started renting large auditoriums and we went into the citywide meetings. I really didn’t want to do this. I was comfortable in the churches; I wanted to stay there. And I didn’t leave until we just had no choice. People were driving sometimes hundreds of miles, only to arrive and there would be no room to seat them. And of course this was creating such problems we felt we had no alternative.

I remember that last revival service I conducted in a church. It was a Sunday morning. (Actually it was not the last service, but it was the last Sunday morning we were in a service.) The service was bound up. It would not function or move. It seemed to be so dead—I had no liberty whatsoever. Right in the middle of the message, while I was preaching, I was subconsciously wondering what in the world was wrong. And God was speaking to my heart and said, “Son, I’ve told you to go into the citywide auditoriums. I have more things that I want you to do, and you are not obeying Me. Until you do, My Spirit will not move.” I’ll never forget that moment.

And if I remember correctly, that was basically the last meeting that we conducted in a church. And, of course, I say that simply because the Lord instructed me to do otherwise, certainly not meaning that it’s wrong to conduct meetings in churches. It isn’t. But God was leading us into a different ministry, and I actually did not want to launch out into the unknown. But then we did, and the crowds started coming. Lives started to be changed. Souls started to be saved—in a magnitude that I had never dreamed possible.

And, of course, I cannot talk about the media without remembering our humble start into publications. In 1970, we began to publish a little four page flyer to list our revival schedules and to advertise our records and tapes. It was just black and white and was printed on inexpensive, uncoated paper. But the blessing of God was on this little publication too. We called it The Evangelist, and we began improving it by adding pages and color. We found this to be an excellent teaching tool to feed the people each month, so we began adding teaching articles and other helps for God’s people… Today, publications of all kinds that we have written can be found in the homes of multiplied thousands of people, bringing instruction and blessing to hungry hearts. In fact, through the media of publications, radio, and records and tapes, God has poured out His blessings on this ministry far more than we could have visualized, and we are grateful to Him. (“Twenty-five Years of Mighty Miracles: A Quarter Century of God’s Goodness”)

Originally, Jimmy recorded a half hour show with marked time for advertisements. Once he developed an audience, he realized he could break a teaching apart. Ten to fifteen minute stretches allowed him to elaborate on a few points before asking listeners to return the next day, the next week. In this way, he broke from other radio ministers with their constant calls for salvation and incessant requests for donations, charity, love offerings, or – simply – money. It was a format he learned from comic books and serialized movies as a boy, you had to keep people coming back for more. Everything was “to be continued” and when he ran out of material, he would preview the next series. He continually promised he would talk about something “next week or the week after” to keep his audience invested, searching, wanting him to answer their questions on the air and bridge the parasocial relationship. He was, after all, one of them – just a country boy from the end of a dirt road who loved Jesus and wanted God to move in his life, their lives, the world entire. He wanted so badly to keep that connection to who he had been and how he grew up, but personal anecdotes had to serve the script. As Frances would remind him, he could actually say something substantial if he stayed focused. No more flowing in the Holy Spirit, no more seeing where things went. Consistency and the development of an audience were tools for filling in auditoriums the next time he was in the area of his audience. Consistency would keep people coming back. Jimmy wanted to keep the Spirit flowing, but Frances wanted to keep the money flowing. Frances would win.

As the years went on, especially once Jimmy and Frances moved into television, Jimmy’s tell became more apparent. He would interrupt and speak over pastors he had invited onto the show. He would jerk his head, crane his neck up and away from his collar, pull at his lapel. His eyes would get wide and wild, darting up or outside the camera frame for a moment. That caged animal was still there, looking for the doors, looking for a way out, looking for prey, doing everything he knew to do to keep from gnawing his own hands off.

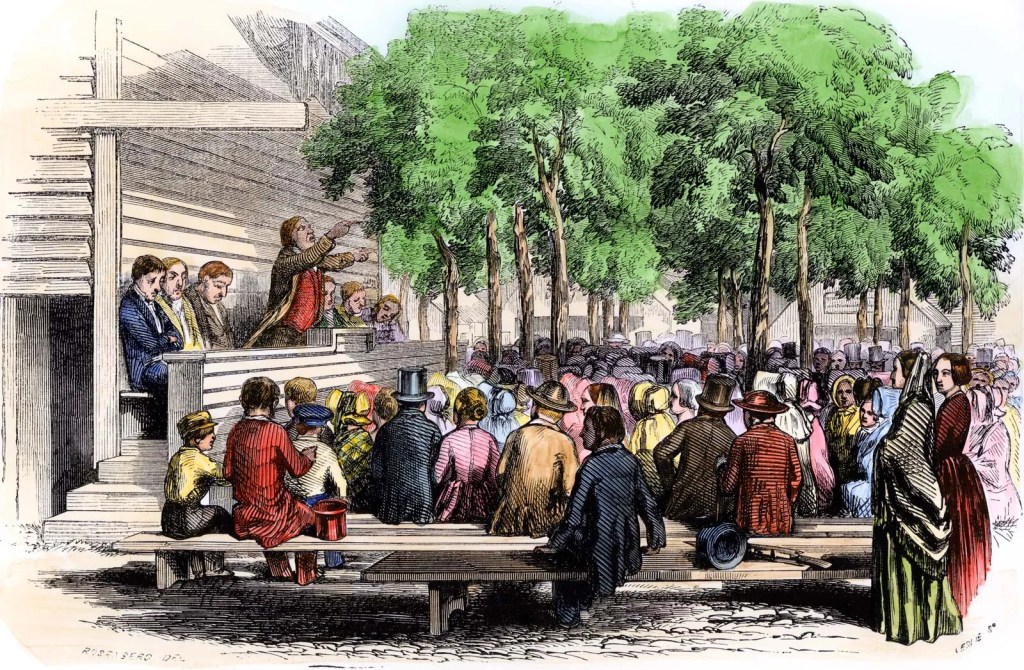

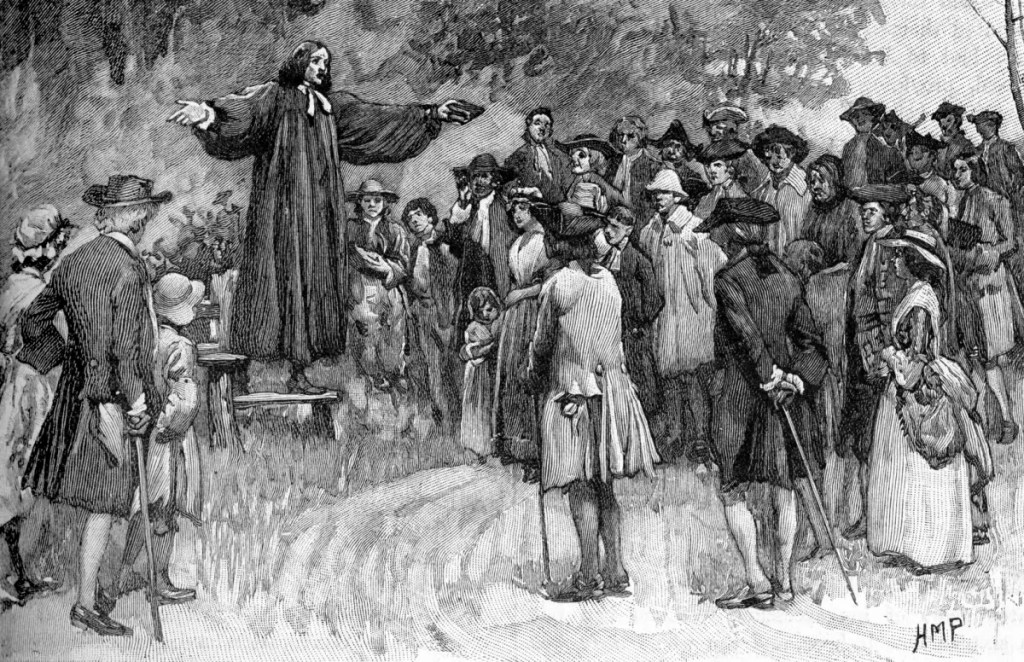

The Campmeeting Hour, the program’s name, came from the camp meetings of the Second Great Awakening, when ministers were innovating a new form of Christianity outside of traditional methods. In England, Dissenters were forbidden from preaching five miles outside of a town, and began to field preach on agreeable farms or in open fields. They were finding new preaching styles as well outside of the brick-and-mortar cathedrals and houses of worship. Families would travel out for the weekend and camp, meeting other families and sharing news.

By the middle of the 18th Century, the Christianity of America had begun to slumber. John Wesley had tried to convert Americans to his religion of the heart, Methodism, when he came to the New World in 1736. He failed miserably and returned to England the following year, believing America an inhospitable land. His emphasis on the heart, rather the mind, continued to germinate but much of the original enthusiasm in America had given way to Calvinism, scientific rationalism, or anti-imperialist politics. Religion just wasn’t meeting people where they were anymore, especially when it supported tyranny in the name of the crown. The disaffected saw church attendance as a social club and noticed that the privileged would attend on Sundays only to trade goods, even slaves. Surely, this was not what the Lord intended for the Sabbath. Churches upheld a form of religion that spoke about obedience to the British crown before loyalty to scripture. And of course zealous Calvinists, inheriting counterculturalism and iconoclasm from their Puritanical ancestors, were quick to believe everyone (except them) would going to Hell for every imaginable reason. As Jonathan Williams declared in his sermon, “Sinners in the Hands of an Anrgy God” (1741),

Yea, God is a great deal more angry with great numbers that are now on earth – yea, doubtless, with many that are now in this congregation, who it may be are at ease – than He is with many of those who are now in the flames of hell.

It is not because God is unmindful of their wickedness, and does not resent it, that He does not let loose His hand and cut them off. God is not altogether such an one as themselves, though they may imagine Him to be so. The wrath of God burns against them, their damnation does not slumber; the pit is prepared, the fire is made ready, the furnace is now hot, ready to receive them; the flames do now rage and glow. The glittering sword is whet, and held over them, and the pit hath opened its mouth under them. The devil stands ready to fall upon them, and seize them as his own, at what moment God shall permit him. They belong to him; he has their souls in his possession, and under his dominion. The scripture represents them as his goods. The devils watch them; they are ever by them at their right hand; they stand waiting for them, like greedy hungry lions that see their prey, and expect to have it… The old serpent is gaping for them; hell opens its mouth wide to receive them.

After the American Revolution had concluded in 1783, a jaw-dropping nine out of ten Southerners were not affiliated with any church at all. In the North, where Christianity had been more of a civil religion, church leaders carried the stain of treason either for their support of the Revolution or, worse, their support of the monarchy. There, the Church of England rebranded itself as the Anglican Church in a desperate hope that Americans would come to forget their loyalty to the crown. Thomas Jefferson famously took a knife to a copy of the Bible, finding accounts of miracles and the rejection of science to be contemptible. A month before his death in 1790, Benjamin Franklin wrote about his indifference toward Christianity to Ezra Stiles.

As to Jesus of Nazareth, my opinion of whom you particularly desire, I think his system of morals and his religion, as he left them to us, the best the world ever saw or is like to see; but I apprehend it has received various corrupting changes, and I have, with most of the present Dissenters in England, some doubts as to his Divinity; though it is a question I do not dogmatize upon, having never studied it, and think it needless to busy myself with it now, when I expect soon an opportunity of knowing the truth with less trouble. I see no harm, however, in its being believed, if that belief has the good consequence.

Americans had won their freedom but were spiritually demoralized. Stiles was, at the time of Franklin’s letter, president of Yale University where he had distinguished himself as a professor of Semitics. Notably, Stiles was also a leader in ecumenical dialogue and showed reluctance of his own to see Jesus apart from a Jewish context. The anti-intellectualism of Puritans, arrogance of Calvinists, isolationism of his fellow theologians, and disarray of civil religion had worn the new nation thin, in the halls of academia as well as the public square and farmer’s fields.

Expanding westward across the Appalachian, Americans found a primitive existence like that of their ancestors. Revolutions felt terribly far away, left behind beyond the mountains. The struggle for life in the midst of uncertainty, where the only certainty was death, compelled many to abandon their morals and virtues. There was no time or energy to work out eternal fate or one’s destiny. Whether an individual was a member of the Elect or the Damned seemed unimportant. People on the frontier drank heavily, domestic violence was to be expected, and by some estimates one in every three brides were pregnant at the time of their wedding. The evil of each day was sufficient to break the strongest of wills. Justice caused a neighbor to disappear here, injustice caused the next to disappear there. Directionless, paranoid, and in need of relief, Americans found comfort in a new wave of revivalism.

The Second Great Awakening, stretching from 1795 to 1835, placed tremendous emphasis on salvation as had the First Great Awakening. It also emphasized social reform, Christian character, temperance, and domestic tranquility – or at least a decline in violence, at minimum. Unlike the First, however, the Second Awakening did not care much for civility or the advance of science. In most respects, it came to see science, politics, rationalism, even religious certainty as indicators of sinfulness. These were the very things that had shackled the nation, rather than liberating. Rationalism failed to speak to the lived experience of Americans who had come to feel that life simply did not make sense. You could apply yourself and still fail. You could do everything in your power to claw out of the morass only to meet with fate or God’s will and either die or see everything you had worked for disappear. Scientific thinking failed to recognize the traditions that people held on to for meaning as they expanded Westward, that they brought with them from Palestine, Germany, Italy, and Ireland. Science could not explain the terrors of the human condition, could not deliver on many of its promises to an impatient population. And politics? Politics had turned neighbor against neighbor, as it would once again a century later.

An aspect of the Second Great Awakening that often gets downplayed is how camp meetings provided a place for Americans to find common cause with one another. These meetings, outside of towns and institutional structures and expectations, allowed Americans to talk with one another, meet new people, and discover shared experiences.

The concept of large-scale communal worship through “camp meetings” had roots in ancient Israel’s Feast of Tabernacles. On the American frontier, they provided a vital religious and social outlet in sparsely populated regions where permanent churches and ordained ministers were scarce. Unlike traditional church services, camp meetings could last several days, drawing thousands from miles around. Simply, people would set up tents or campers in a large clearing. These social gatherings reunited families and friends; beyond this, people engaged in various recreational and cultural activities. They talked about politics and found they were more alike than not, then joined with those already attending the communal worship sessions of preaching, prayer, and hymn singing. Some meetings featured “wild enthusiasm and hysteria,” with experiences like sudden conversion and calls to the “anxious bench” to seek Christ’s cause until the late 19th century, when mainstream Protestant denominations like the Methodists, Baptists, and Presbyterians could no longer tolerate excessive (or, as many came to believe, performative) displays of emotionalism and behaviors associated with traditional camp meetings. By 1890, their decline in popularity was met with a matching rise in permanent churches, camp meetings continued and were adapted by various denominations, including Methodists, Baptists, and later, Seventh-day Adventists and Pentecostals. Entering a new century, some of these groups recast these events – within the hierarchical church structure, where emotionalism could be “disciplined” – as seasonal Bible Conferences or revivals but many Christian denominations, especially “Mainline” churches, discarded, recast, or tried to forget them and their tradition’s revivalist history while the less-respected Wesleyan-Holiness and Pentecostal groups unapologetically embraced the spirit of the frontier camp meeting, and particularly emotional displays, as a testament to their faithfulness.

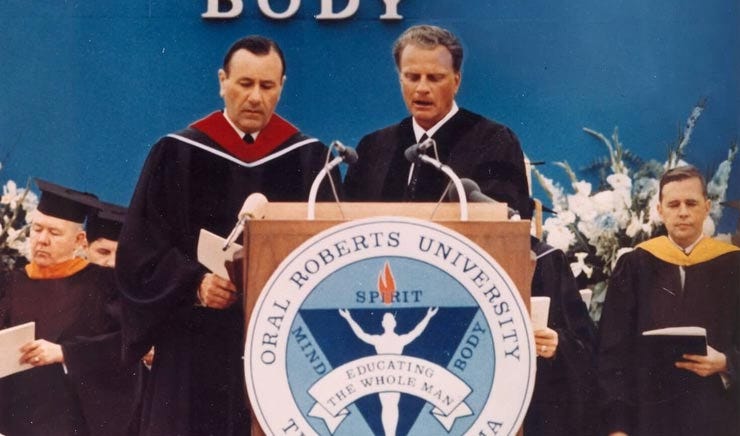

When Jimmy named his program The Camp Meeting Hour, it was a clarion call to the disaffected and forgotten. Like Oral Roberts before him, Jimmy wasn’t shy about his belief in the miraculous and supernatural. He wasn’t shy about his emotionalism either, which was very different from his predecessor. In 1963, Roberts founded a school, a private, nonsectarian, liberal arts institution in the State of Oklahoma bearing his name. Two years later, in 1965, Oral Roberts University (ORU) held their first classes with an enrollment of 303 students. At the time of its dedication on April 2, 1967, the university had eight completed buildings situated on a 420-acre campus. Billy Graham was even on hand and was the chief speaker at the dedication ceremony for ORU, and appeared together with the healing minister on a primetime television special to dedicate the university’s new Mabee Center five years later. Graham’s participation was significant as it helped legitimize Roberts’ ministry within the broader evangelical world, bridging the gap between the Charismatic and mainstream Evangelical movements.

But Jimmy Swaggart wasn’t either of those things. The camp meetings he held at his church in Baton Rouge, the ones he spoke at in arenas around the United States, and the kind he presented on his radio program were not for shoulder-rubbing, schmoozing, or photo opportunities. His meetings, he was famous for saying, were “old fashioned, heartfelt, Holy Ghost, devil chasin’, sin killin’, true blue, red hot, blood bought, God given, Jesus lovin’, indoor camp meeting!” and he brought that same energy and enthusiasm to The Camp Meeting Hour.

No. Jimmy Swaggart was many things, but he wasn’t a Charismatic.

In the coming decade, he wouldn’t care much for Evangelicalism either.

Continued in Chapter 13(B)