John “the Beloved” is not a strongly defined figure in the Christian scriptures. He rests on Jesus’ chest, breast, bosom – depending on your preferred translation of the Bible, there are strong homosexual undertones here. I’m not fully convinced that John is, in fact, gay. But there is textual evidence that John’s love for Jesus is more than philial. To understand John’s ethic of love, we first need to understand what the author of John’s gospel means when they describe John as “the beloved disciple.”

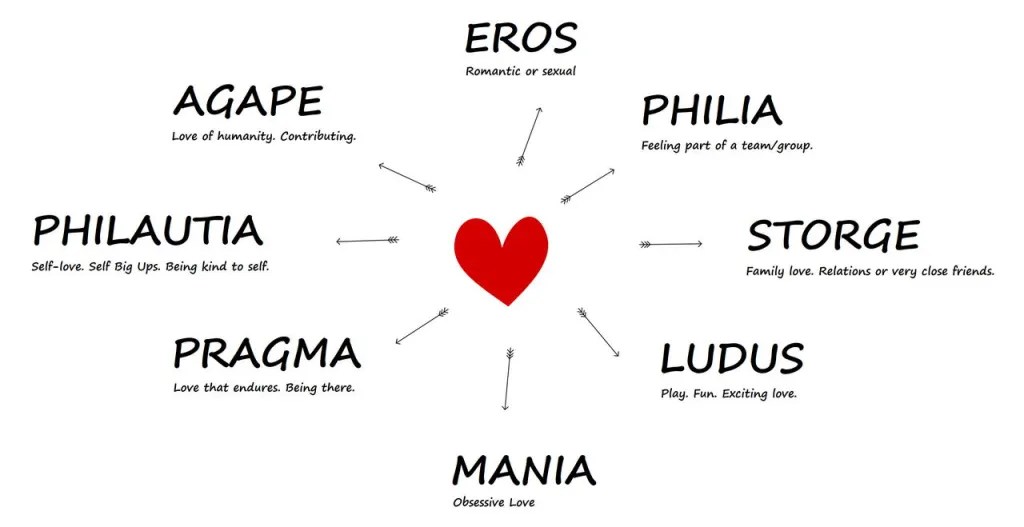

In the ancient world, there were six unique words for love. They are not encyclical, as though these are the only ways humans did, could, or would express love.

Eros, of course, is the erotic form of love. Phlia is an affectionate expression of love. For example, Philadelphia is known as the “city of brotherly love” toward one’s neighbors and fellow citizens. Storge is a familiar kind of love, like the kind one presumably has for their family members. You might love them out of obligation or you might love them because of proximity, but familiarity is a constant. Ludos is a playful kind of love, given less attention by the Greek philosophers because it is perceived as childish or immature, not fully developed. Taken to excess, it becomes a fifth kind of love, mania, which presents as an obsession that is often unpredictable. Pragma, the opposite of mania, is an enduring love not given to obsession or possession but constancy and dedication. Love, for the pragmatist, is hard work and takes time. Then there is philautia, a love for self (or self-love), and its opposite agape, a selfless love.

We might observe in these a matrix. One is like its near neighbor, but each has an opposite. Love is contrary, we might say. It is undefined, despite many efforts to define it.

In the Gospel of John (13:23, 19:26, 21:7, 21:20), John is “the one Jesus loved” with agape love, a selflessness. In 20:2, the tone shifts. John is the one Jesus loves like a brother (phileo). It is worth noting that John’s love and belovedness is always observed. In each use of “the disciple Jesus loved” or “the beloved disciple” or “the one Jesus loved”, other prominent figures are present. The disciples (13:2), Mary, the mother of Jesus (19:26), Mary Magdalene (21:7) and Peter (21:7 and 20) are there for contrast, juxtaposition, and chiaroscuro to the image being presented. The author of John’s Gospel vanishes John as a character as Jesus is being crucified. Jesus, dying, tells his mother that John the beloved will take care of her. Turning to John, he insists that John care for Mary, his mother. Once more, there are witnesses to the “love” between John and Jesus. Mary, Jesus’ mother, is present, of course, as well as Mary Magdalene, and Jesus’ aunt, who is either also named Mary and the wife of Clopas, or (no small thing this) an unnamed aunt as well as another woman, Mary, who is the wife of someone named Clopas. Clearly, the author of the Gospel of John (the Beloved!) is trying to show that John is already known and embraced by Jesus’ family. He is not merely “like a brother” (phileo) but exceedingly loved (agape) and tasked with the responsibility of continuing to be part of the family when Jesus dies.

Why is any of this important?

Because Jesus is many things. But he is more of those things, adopting new titles and embodying special divinity, in John’s Gospel. Jesus is not this or that, or this and that. Jesus is everything, all at once, at the same time. The author of the Gospel of John is writing a wild love letter about Jesus. Jesus is not just someone who taught things and then died as in the Gospel of Mark, not the important political figure of Luke’s Gospel, or the Jewish messiah-savior of Matthew’s Gospel. For John, Jesus is the Lord of time and space, having always existed before the world was even created. For John, Jesus’s death is something of a punchline.

Jesus? Dead? The God of All Things has died? (hysterical laughter) Good one! Tell us another tall tale! As if one could just walk into a garden, arrest God, and then kill the Creator of All, the Pre-Existent One who resides outside of the great philosophical insight we call “time” and “place.” You people sound so stupid. He died? Ridiculous!

John continues this message years later, presumably after Jesus’ mother Mary has died. While the other apostles were busy making names for themselves, John was sidelined. He got left behind. Tasked with domestic responsibilities, he is not at all like Paul or Peter, making Jesus into a central figure of theology. John is forgotten. He emerges in short letters, relegated to the back of the Christian scriptures and barely offering anything substantial. Most commentaries tuck the letters of John in with other works, like the letters of Peter or the long arc of Hebrews because John’s works are not substantial enough to stand on their own. Historically, their inclusion in the canon of the Christian scriptures was more out of obligation than anything else. After all, they offer nothing substantial and thus, nothing controversial. They endure with little discussion.

Which makes it all the more unsettling when a reader arrives at John’s magnum opus, Revelation, which is singular. Insightful. Divine. Definitive. Psychotic.

John’s love ethic is so central to the Christian ethos that it comes to define the new religious movement. So when things go sideways in Revelation, Jesus is pulled forward into the narrative as one really angry dude coming down from Heaven with his pissed-off, beefed-up angel army.

Which is actually pretty gay, when you think about it.

I’m not saying Jesus was gay. Or that John was.

But John sure does have a flair for showering Jesus in elaborate imagery. For what will come to be described as Camp style.

So, as the Early Church begins to sort through the Gospels and the apocryphal stories about Jesus – like the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, where a child Jesus turns clay mounds into actual, living and flying pigeons so he can play with them – there are hundreds of different Jesuses. In the Gospel of Thomas (not the Infancy one, but simply the Gospel of Thomas), Jesus engages in the Socratic method with his followers until they are all reduced to silence. Jesus is so… well… off his fucking rocker, so detached from reality, that the apostles are silent as Jesus continues to ramble on. They seem to be glancing at one another, there off the page, wondering if Jesus had a bit too much sour wine for his own good. For example, the Gospel of Thomas concludes with Peter saying women are not worthy to be alive and Jesus seems to agree. He doesn’t contradict Peter anyway, but instead adds that women will only make it into Heaven if they become like men (114). What does that even mean? No one knows. Again, Jesus is engaging in a dialogue with his followers that resembles the Socratic Method – if the Socratic Method wasn’t actually based on logic and reason. It goes off the rails pretty quickly, and no one knows what to say.

Jesus has lost his damn mind. But the Gospel of Thomas is not singular. These strange characterizations of Jesus, the insertion of his politics and approach to gender, this is the kind of stuff people made up about him. In one account, a young Jesus allegedly kneads clay into toys and makes these toys come alive. Near the end of his life, Jesus is running out of material and things to say, so maybe everything he says isn’t, you know, fully developed. They’re not all bangers. At the end of the Gospel of Thomas, the followers come to Jesus and tell him they are going to pray and fast. Makes sense. Jesus replies, “What is the sin that I have committed, or wherein have I been defeated?” (104) Like, read the room, man. Jesus just ordered some nachos! Don’t ruin his good time!

“Jesus said, ‘Seek and you will find. Yet, what you asked me about in former times and which I did not tell you then, now I do desire to tell, but you do not inquire after it’” (92). Okay, so like… our bad. Will you tell us now, if we ask?

Right after this, “Jesus said, ‘He who knows the father and the mother will be called the son of a harlot’” (105). I’m sorry, bruh. You lost me on that one.

That these stories exist, and in some cases persist, demands our attention not because any of the non-canonical or even canonical versions of Jesus make sense, but because they reflect different expressions of Jesus that religious communities wanted. When Jesus says women need to be more like men in The Gospel of Thomas, that tells me that there existed a community that wanted to keep women out entirely.

Somewhere between John’s Gospel of love and Matthew’s biography, squarely making Jesus out to be a Jew (and not, anachronistically, a Christian), the Christian communities right after Jesus died wanted more. It wasn’t enough to die for the whole world, to set people free, to save them.

They wanted a Jesus who also hated women. Who had a short temper. Who wanted to burn the world down. Who wanted revenge. Who was magic.

And it’s not just Jesus, mind you. These other gospels, these other stories put words not only in Jesus’ mouth, they do the same thing with their fellow followers, disciples, and apostles. It is Peter in the Gospel of Thomas, not Jesus, who starts the conversation about killing women. Peter says they, women, “They are not worthy of life” (114). Still, tellingly, Jesus says women won’t even be able to go to Heaven unless they become men. That is a great deal of outright hatred for women that not only is absent from the Gospels, but directly contradicts the Jesus of the Gospels. Strange as Jesus may appear in the Gospel of Thomas, there are people just like these early followers today. There are people calling themselves Christian who legitimately feel women should be silenced (like Paul does) and who believe women are “not worthy of life” (like Peter does) because… what? They are too emotional? Too hysterical? Too moody? Or is it as simple as the page reads – women need a penis to get to Heaven? We might say this is ridiculous, but even dialed down, the teachings of the Latter Day Saints insist that one will never be able to achieve their full measure of dignity in eternal life unless they are married. Women, even in the afterlife, still need to get that good dick and are incomplete without it.

This Jesus, the one who hates women, is not the Jesus of the Gospels. The Jesus of the Gospels, to these people and to many self-professed Christians today (with their “traditional marriages” and “Western values”, i.e. White Suprmacy), has been “pussified.” Unsatisfied with the Jesus of the Gospels, they make shit up. They make shit up trying to reclaim Jesus as a hypermasculine bro-dude who shoots the shit with his Bros because, after all, nothing is more logical than Bros before Hoes.

The Jesus of David Duke, the Ku Klux Klan, the White Supremacists, who think Jesus was not actually Jewish but a White Aryan with blonde hair and blue eyes? Yep. This version of Jesus is an old one, too. Part of the reason Matthew’s Gospel exists is because there were people in the early churches who were claiming Jesus wasn’t actually Jewish. Antisemitism is not a new thing, and it has tried to force Jesus – who was born as a Jew, lived as a Jew, and died as a Jew – to be something other than what he actually was. It has tried repeatedly, and desperately, to wrench Jesus out of his original context.

So the Jesus of John’s Gospel, the Jesus who teaches, preaches, and embodies an ethic of love is merely one more Jesus that may or may not be true. The expectation during Jesus’ life, at least among those close to him who left their jobs and families to be with Jesus, was that he would somehow unite the disenfranchised into a People’s Army. They wanted a revolution. Even to the end, the very night that Jesus was arrested, Peter was prepared to kill for Jesus. Two other followers, James and John the sons of Zebedee, asked Jesus who would sit beside him in the coming kingdom. Even John, much much later, will set aside his love ethic for an expectation of violence and political upheaval. So John’s earlier depiction of Jesus as the divine incarnation of love is very much at odds with the expectations while Jesus was alive and immediately after his execution.

No wonder then that John’s depiction of Jesus was so compelling. Clearly, there had been miscommunications and misunderstandings. Jesus had died. He did not lead an armed rebellion. Jesus had died. He did not defeat Rome. Maybe Jesus was the love we made along the journey, right? Maybe Jesus never wanted to be king! Out with the old king, in with the new king, long live the king and heavy is the head that wears the crown. Maybe Jesus lived (and died) to teach people how to love.

This is a much tamer, palatable, non-revolutionary, non-threatening understanding of Jesus. One that doesn’t make waves, doesn’t upset the rich and powerful but quietly changes the heart over time, even decades. There was a good reason to soften the narrative. John the Baptist was executed for naming political corruption and adultery. Jesus was executed for challenging the religious order. Christians and the followers of John the Baptist, together with other revolutionaries, the Zealots, and the enshrinement of the Maccabean Revolt years earlier had created an environment where Roman politicians, soldiers, civil leaders, and the wealthy felt continually threatened. Paranoia prevailed. Emperor Nero felt threatened by the political rhetoric of the Christian communities whenever they emphasized “King Jesus.” As should be obvious, the tendency of Christians to congregate with one another. As we see in our headlines today, wherever a crowd is forming, police are sure to follow. Which is to say: Love is often an action. An action of “showing up.” And even an ethic like love can be misunderstood.

Which, again, raises several concerns when one reaches Revelation, where an elderly John, whose heart has been changed over the decades, expresses open contempt, even hatred, for the Christian churches. Either John suppressed his anger for the love ethic and spent his years in exile from the activity of the Christian churches hardening those teachings, or this change is evidence that even the most idealistic of believers in Jesus will, given enough time to endure political oppression and religious debate, turn on their friends and neighbors if they present a different Jesus than the one we know.

Bart Ehrman, professor of Religious Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, says that when he was completing his graduate work, he unintentionally set off a round of debate among his oversight committee.

It was in graduate school, I obviously always knew that Matthew and John were not the same gospel and that John had a different portrayal of Jesus than Matthew, and that Luke and Mark were different, and Paul had – I mean I realized that there were different emphases but I think I always understood it as different emphases rather than distinctly different portrayals. It wasn’t until I was in graduate school and I started recognizing not just that there’s like a contradiction here or there in the gospels, but that the overall messages were not the same. I started noticing that Paul doesn’t talk about Jesus’ teachings, you know? Like, it’s not a big deal. He quotes two of them! And so I realized, you know, his view isn’t the same as Mark’s because Mark spends a lot of time on Jesus’ miracles and Paul doesn’t talk about Jesus’ miracles. Matthew has long discourses [by Jesus]. Paul doesn’t have discourses [by Jesus], and I started realizing it’s not just that one is emphasizing something. They actually have a different thing they’re trying to say about Jesus. They have a different portrayal of Jesus. Eventually, I came to see that these different authors, on a deep level, actually have different understandings of both who Jesus was and why he was important; that strikes me as significant because it isn’t that the New Testament portrays a unified figure Jesus. There are different portrayals – and it’s not that you should reconcile them. It’s not that like you try and mush them together [from] the twenty-seven portrayals into one portrayal, because then you’re not accepting the portrayal of any one of them!”

There were a lot of variations in how early Christians understood or viewed Jesus. The legend of the Early Church agreeing on things not only has no textual or historical support, but overwhelming contradictory evidence – including the Bible itself. The Gospel of Luke was written to try and get the truth out of competing, conflicting, and contradictory narratives surrounding Jesus, Much later, Paul will challenge some of the teachings or “folk tales” that were circulating within the Christian community. John does something similar in his epistles, and the final book of the Christian Bible, Revelation, denounces churches for false doctrine and behaviors that run contrary to the Christian community. Hardly a time of shared understandings and permissiveness in different interpretations.

While there were five primary considerations of Jesus in the Early Church, the Gospels focus on entirely different things; Mark’s gospel includes no teachings. The earliest manuscripts of the Gospel of Mark do not even include Jesus’ resurrection, while John’s gospel emphasizes a cosmological Christ whose entire ministry was defined by the miraculous. Ehrman continues to explain.

The Jesus community had not even left the First Century yet, and the narratives continued to grow. By the Second Century, disagreements within Christianity had one side arguing that Jesus was entirely human, born to Joseph and Mary how every other human is produced – through sex. Nothing remarkable about that. He was a righteous person, perhaps exceptionally so, but still entirely (and unremarkably) human. They rejected a supposed divine or supernatural intervention by God, and many were even offended by the notion. After all, the Greek gods were notorious for having sex with humans and the stories of God “overshadowing” Mary to get her pregnant sounded pretty pagan as they depicted God as a rapist.

Other groups claimed Jesus was not human at all. While some groups erased God from the story, as it was impossible for a spiritual being to become human, others tried to erase Mary from the story because she was human. Jesus was immaculately born and Mary’s role, when it inconveniently appeared, was minimized. Jesus was God on Earth, a divine being who did not have to eat, sleep, walk, or perform any other function of humanity and bodied life. Jesus was, as they saw it, here for appearances but was not flesh and blood like his followers. This distance between Jesus’ experience and the experiences of his followers created yet another emotionally distant god, unable to understand the conditions in which humans found themselves but at least Jesus was not corrupted and tainted by the human experience.

The ends of these two narratives, the two figures Jesus and Christ, help explain some of the disagreements and contradictory claims of the Gospels, the correctives in Paul’s epistles to the churches of the Mediterranean, and much later the disagreements that existed and continued to grow in the Early Church. Historians, trying to understand the Christian communities in the first three hundred years after Jesus’ death, often try to focus on similarities rather the abundance of differences.

And so those, you know, those are some of the extremes but you have all sorts options by people in the Second Century and so the big that that has been long known and recognized by scholars but the big issue ended up being in the last several hundred years is whether the whether the variety you find later can be represented earlier. You don’t have these extreme views earlier but do you have different understandings of who Jesus is even in the New Testament. We see this same range of understandings within the New Testament. [It is not] a more coherent, unified vision. You get a definite range [and] there are striking differences. I would say that the differences get exaggerated over time as people will kind of take the ball and run with it in different directions but you clearly have very very different views of Jesus throughout the New Testament.

To clarify, the five primary considerations of Jesus in the Early Church but the Gospels (because they are not assembled until later) are as follows:

- Peter’s narrative: Jesus is a fast-moving revolutionary here to restore the Jewish way of life.

- James’s narrative: Jesus embodied self-sacrifice. The only way Christians can continue his legacy is to serve in a similar way.

- Paul’s narrative: Jesus was the fulfillment of Jewish expectations and nothing more is required of the believer than to simply have faith in this and wait for either death or Jesus to come back and lead a new Exodus – not an armed rebellion, but a quiet abandonment of Rome.

- John’s narrative: Jesus won;t be coming back for a long, long time. Until then, the believer must realize that Jesus embodied love and the believer must also embody love. What this means is entirely subjective and situational.

- The Marys’ narrative: Jesus did not even support oppression of one another on the basis of gender, so all this “in” and “out” stuff is a waste of time.

Said differently, we might also notice that

- Peter’s narrative empowers war. Jesus won’t come back unless we start the war now.

- James’ narrative empowers public service. Jesus won’t come back, but we’re still here.

- Paul’s narrative empowers self. Jesus may or may not come back, so let’s continue with things as they are and see what happens.

- John’s narrative empowers small actions, whenever possible. Jesus won’t be coming back for a long time, so we need to take care of one another.

- The Mary’s narrative empowers changes in daily life, especially in one’s own family. Jesus’ current address is not important. You treat people well, regardless of what Jesus is doing. As for starting wars? Do you even realize who bears the burden of that? Women, children, the “least of these.” The rest of you are always so eager to send your children to war and leave women behind. Nothing will change until you stop making them collateral damage. Women have sacrificed their bodies – just like Jesus – to make this point, and no one seems to get it yet. Exchanging one master for another fails to recognize the immorality of having a “master” at all.

One thought on “How Many Jesuses Are There? Part 2”