Let’s get this out of the way: One.

Okay? One.

But also… four.

And, biblically speaking, maybe five more besides those original four.

Historically, okay, yes, a couple hundred more. Which is going to sound contradictory for most of you, I imagine, but it’s more accurate than most people want to admit.

(Cue the comments from people who won’t even bother to read past this point.)

All of the ways (plural) that early Christians understood, wrote, sermonized, spiritualized, prayed to, rejected, and embraced Jesus as Christ are quite literally untraceable at this point. Conversations were never written down or recorded. Jesus’ teachings, whatever they actually were, inspired a handful of people to write them down – evidence that people were literate and could write in the Ancient World. The truth is, however, that much of what Jesus said and did has been forgotten or set aside with time. In written records like the Gospels, Jesus says things that are provocative, insulting, generous, inspirational, sarcastic, passive-aggressive, and likely to destroy one’s worldview, politics, and theologically capitalized Truths if they dwell on them for too long. These we see written down. These were the headline-grabbing stories about him.

His behaviors, observed by those who supposedly knew him best, seem at odds with his teachings. He watches people, like a poor widow who gives her last coin. He approaches a Samaritan woman at a well and begins talking about her sex life. Another time, a woman approaches Jesus for help. He is so insulting to her that she says, “Look, Buddy. You’re being a real jerk. Even dogs get crumbs. Help me out here. Treat me better than a dog.” As for Jesus’ inner life, we have no record. Did he paint? Did he even like paintings? Who was his favorite musician? All of this is conjecture. The Gospel authors, it seems, are not just negligent regarding Jesus’ formative years but intentionally forget, overlook, erase them. They emphasize Jesus’ birth, his Magical Mystery Lecture Tour, and ultimately his death. They will eulogize him and eventually resurrect his memory, but the fact is that the common reader may still be left with legitimate questions about why people cared so much and why, if Jesus was so important, these authors would miss major biographical details that would provide more insight.

Paul, for example, never met Jesus. If he had, he would have told us. He wasn’t shy about telling people that he went to the best schools and knew the best people. Apparently, the Jewish leaders Paul grew up listening to, studying under, training with, and befriending never met Jesus either or, again, he would have said so. Again, he isn’t shy about his intellectual pedigree. He’s not shy with his criticisms either. An intensive read shows one of Paul’s teachers may have been involved in the death of Jesus, but scholars also say including him may have been a later edit by someone who wanted to make a tangential connection. The fact remains that Paul, the most outspoken follower of Jesus Christ in the Christian Scriptures, never actually met Jesus and cannot speak to the gaps in our knowledge either.

The closest Paul would ever come to meeting Jesus would be in his capacity as execution administrator, killing off those who knew and believed in the Christ. He would have heard their testimonies and hopes, probably doing everything in his power to get them to recant or deny their savior moments before having them killed. Which he openly admits. That part is no secret and, in fact, defines him. Paul killed a lot of people. Yet, having never met Jesus, Paul presumes to know Jesus and speak on his behalf posthumously, giving the memory of Jesus substance and meaning for the last two thousand years.

Those who allegedly knew Jesus best, like his brother James, offer very little insight into his character, his home life, his sense of humor, or his politics. The “beloved disciple” John says Jesus was alive before the world was created at the start of his Gospel, and later in his Revelation that Jesus will be alive when the world is destroyed. This Jesus, the one remembered by John, is inconsistent and – to be blunt – maybe not well, psychologically. John frames Jesus as the Lord of Time and Space, a Cosmological Adventurer who visits Earth and then skips town to… well… go do some stuff. We’re not sure. But you can be sure of this: Jesus is going to be really angry when he comes back. He’s going to be angry with how people do religion in temples, how churches exploit people and lie about it, how false teachers erode the Good News that Jesus taught with weird misunderstandings and make-believe, with women riding dragons (whatever that means) and whoring around. Jesus will be angry about the dead people under the floorboards – In fact, you know what? Jesus is going to pull those dead people up from underneath the floorboards! You hear me?! And they’re never going to stop talking about the people who abused and murdered them either! And don’t you dare add any other details to any of this or try to make sense of it or you’ll be damned forever and ever! – This Jesus, the Jesus of love and space and time and peace, is always angry. He’s got a bad temper. He is God and also Judge. And He will one day destroy everything God has created.

Even still, who is Jesus between eternity past and eternity future? Not important enough to describe. What made Jesus so angry as a child? What shaped him to make him so violent? We don’t know. He’s peaceful and loving in the Gospel, and mad as Hell in Revelation. We simply don’t know what happened.

Here’s what I think:

After Jesus dies, his fanbase didn’t know what to do. We see this all the time. A celebrity dies, and people who never even met them are upset. February 3, 1959, is still known as “The Day the Music Died” when a plane crash killed singers Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson near Clear Lake, Iowa. The tragedy was later immortalized in 1971 with Don McLean’s song “American Pie”.

When Princess Diana of Wales died in 1997, the world mourned. Her death, while sad, caused millions to reflect on their own lives and what their legacy would be when they died.

Many fans are convinced that Tupac Shakur, who died in 1996, is still alive somewhere, producing albums and will one day release a new album that will bring peace to the world. Whether he is or is not living somewhere in South Florida though, he inspired other artists to make new music. Which is a form of new life, perhaps even divinity, to inspire others to create new, beautiful, and inspiring works “in his image.”

So, it’s not that strange or quaint or primitive that Jesus’ followers would be similarly affected, thousands of years ago. When Jesus made comments about the conditions of his time – the poor widow who gave what little she had, for example, to help someone else who needed help – and performed miracles – like evicting demons from those who were unwell – and explained that neither the occupying Roman soldiers and craven religious leaders would define him, this makes for inspiring stuff. Religious language to explain oppression? Religious language to articulate the harsh lived experience? Jesus is still inspiring, these many years later. That there was a subgroup of Jewish people who enjoyed or “followed” Jesus was not strange. There were several popular groups within the Jewish communities around Jerusalem and the Galilee region. One more group wouldn’t have attracted too much attention, at least not initially. Then Jesus had to get political and say things about how the religious leaders in Jerusalem were corrupt. That would have upset some people. He went further, though. Jesus said that the union of Jews with Rome was offensive, that it contradicted the shared Jewish narrative of abandoning and bankrupting empires. Did the religious leaders understand this? Couldn’t they see the ungodliness of their behavior? Or were they truly so warped by their greed and power, that they believed they exploiting their own people was holy? They could pray as much as they wanted as loudly as they wanted, but God would reject them. Only the true sons and daughters of God – Jesus said he was one of them – would inherit the coming kingdom of God.

Well, that surely pissed a few people off. Worse, it gave voice to the complaints of common people. Jesus’ teachings cut to the heart of religion and exposed a moral cancer of religion, greed, and politics still familiar today. That this breakaway cult from Judaism, the “Christians”, kept going and – worse! – growing is a testament to the fact that Jesus’ sermons, teachings, life, and ultimately death, actually meant something to people.

As with everyone who dies, Jesus’ legacy went in different directions for different reasons. Alexander the Great’s empire tore itself apart once he died because of the competing visions, rivalries and self-interest of his successors. It was thought that distance would help relieve the Diadochi, the rival generals, families, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 B.C. Each general would, it was believed, be content in their own corner of the empire. It was not to be so. Instead, their competing visions tore the Greek empire apart.

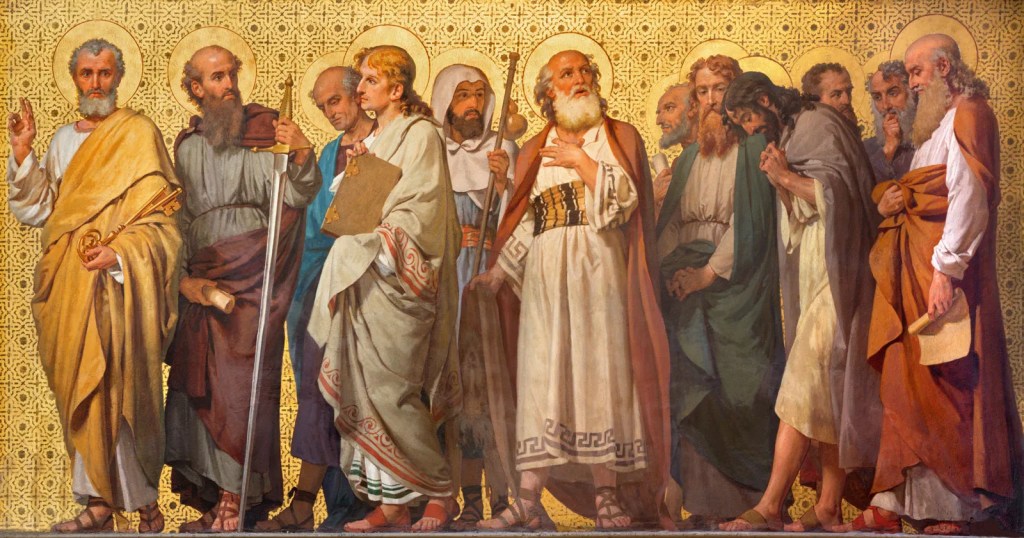

In the same way, three centuries later, five major strands of Christianity emphasizing different vantages of Jesus and articulating different messages, different understandings will emerge from Jesus’ grave.

One of the earliest accusations against the Christian communities was their tendency to conduct “love feasts” which were misunderstood by non-Christians to mean orgies. Orgies were not unheard of in Rome. And they weren’t necessarily bad. They weren’t even shameful. Many of the other religions at the time, like Cybele, had religious rites that were sexual in nature. Apart from religious practices, pederasty was the practice of an older man introducing a younger man to the adventures of sex. Sometimes, this meant – echem – direct lessons. Other times, it meant encouraging (and funding) the boy to visit prostitutes in the area. Presumably, women – at least women with enough privilege and wealth to protect such activities – may have done something similar. In the book of Genesis, long before the Gospels, Potiphar’s wife feels a sense of entitlement to the sexual services of her husband’s workers. Closer to the time of Jesus, Cleopatra was known to use bees in a small tube as an antique vibrator. Julia the Elder, daughter of the first Roman emperor Caesar Augustus, is almost universally remembered for her flagrant and promiscuous conduct. Marcus Velleius Paterculus describes Julia the Elder as “tainted by luxury or lust”, listing among her lovers Iullus Antonius, Quintius Crispinus, Appius Claudius, Sempronius Gracchus, and Cornelius Scipio. Her sexual exploits defined her. Seneca the Younger refers to “adulterers admitted in droves” and Pliny the Elder calls her an “exemplum licentiae.” Dio Cassius mentions “revels and drinking parties by night in the Forum and even upon the Rostra.” Seneca explains that the Rostra was the place where “her father had proposed a law against adultery”, and yet she had chosen the place for her “debaucheries” in an act of sexual excess and wantonness. Seneca then goes further, contextualizing this behavior as prostitution: “laying aside the role of adulteress, she there [in the Forum] sold her favours, and sought the right to every indulgence with even an unknown paramour.” Prostitution then was a way to contain the sexual appetite in parallel to Paul’s teaching in 1 Corinthians (7:9) that marriage is how Christians should constrain their own sexual appetites.

All of this to say that the early critics of the Christian community saw in them something immediately familiar. At odds with their stated ethic, perhaps. But very familiar. When Christians spoke of love, when they became defined by love – even if their expression of love was misunderstood, lampooned, and ridiculed – “Love? Ha! I bet it is, you perverts!” – it remains evidence that the love ethic was something that had come to define their communities. Though the jokes made at their expense may have been a misunderstanding of the Christian message, perhaps even an intentional corruption of it by those who took offense, already had a religion they nominally subscribed to or regularly practiced, or simply wanted to slander, this is still a strong testament to one of the messages of early Christianity, that of a love ethic.

Not all Christians emphasized the love ethic. They subscribe to different understandings, different emphases which do not directly contradict the love ethic, but prioritize these alternatives. Peter, for example, seems to emphasize immediacy and activity. This enthusiasm is indiscriminate. Peter swears to protect Jesus shortly before he is arrested, but by the next morning, Peter is on the run. He runs to the tomb a few days later when there are reports of Jesus’ return from the dead, but then Peter runs to the shore where he takes up fishing again. Jesus, now revealed to be alive, visits Peter and asks him to focus his energy toward teaching. Peter instead reappears among the Early Church members, claiming he has had a vision. He says Jesus visited him and told him to proclaim salvation to all nations and races, not just his fellow Jews. Evangelism and innovation become the ethic he leaves behind. Peter fails, and time will show that his ethic fails. Uncriticial thinking, lack of planning, lack of substance, the tendency to insist where one is not welcome or wanted (and the ways in which this will be exploited time and again by colonial and nationalist tendencies) are decidedly Christian qualities. The legacy of evangelism, of traveling and being on-the-go, of doing new and innovative things – even if you fail, even if you hurt people, and especially when you rewrite longstanding traditions to suit your own interests – is also decidedly Christian.

James, Jesus’ brother, becomes the head of the church in Jerusalem, overseeing policy and polity. He focuses his attention toward helping the poor, broken families, and education. Noble pursuits, these. In the latter half of the Christian scriptures, James reduces his ethic to the maxim, “faith, without works,” or faith without action to substantiate your faith claims, “is dead.” With the Petrine ethic so immediately visible and recognizable, it is easy to forget the centuries of Christians who have quietly plugged away at bettering their communities like James. Those who have stood for social justice, for critical thinking, for a practical and material faith that stands in contrast to the personalized “acceptance” of Jesus in one’s heart by many Christians and especially Evangelicals.

Paul, obviously, characterizes Jesus as the fulfillment of prophecies made long ago. His Jesus is decidedly Jewish – but a Hellenized Jew. Paul’s Jesus is radical in his divinity, but not in his politic. Which is to say, Paul’s Jesus “baptizes” and sacrilizes the Roman way of life. It is not, to be clear, a Jesus that is reflected by those who knew Jesus. It is not the Jesus of the Gospel traditions.

Paul emphasizes the logic and reason and recognizability of Jesus, but does so from a distance. He philosophizes on Jesus. He does not reflect Jesus’ teachings. Does not try to theologize Jesus’ miracles, legitimize Jesus’ teachings, does not turn his readers back to the traditions about Jesus from those who stood in the crowds listening to him, witnessed the alleged miracles, or traveled with Jesus while he was still alive. And here, ironically, Paul’s Jesus is decidedly not the Jesus of the Gospels. The Jesus that Paul writes about is not the Jesus known by those who knew him.

Paul admits that he never met Jesus, and so he fabricates a story – like Peter – of a heavenly vision. This Jesus, the one of visions and divine oracles in the sky, appears to Paul and places demands upon him. This should be one of the first clues to a reader that Paul is about to get things really, really wrong. Jesus never demanded things of people in the Gospels. He softly, passively (perhaps even passive-aggressively) spoke in parables to get people to make their own decisions. He got angry. He wept. But he did not demand things. Jesus did not show up, a giant head in the sky with wide eyes, to demand an account of anyone’s behavior. In fairness, he didn’t need to. It was enough to be alive and look people in the face, to hold their hands, to be close to them. In fact, his closest followers criticized him for getting too close to people. For being too public with his familiarity. For speaking with a woman, for example, who had many husbands. Jesus did not condemn the woman. He talked to her and, in the process of conversation, she realized she needed to make changes in her relationships. That was the extent of his “demand,” talking to people, having meals with them, telling them to come down from trees and other high places – physically as much as existentially – to join the movement. This Jesus, the one who lived among the people, did not stand at a distance. He did not appear just to one person, privately, either to shout commands or to whisper sweet affirmations, as Jesus does in Paul’s theological essays.

Nevertheless, Paul’s Jesus will be pulled out – shockingly, profanely, contrarily – to defend the Roman occupation. Paul encourages the churches to obey Rome. To not make waves, to keep the status quo, to avoid conflict, to pray for unjust rulers and forgive them (for murdering one’s neighbors? For crippling citizens with taxation? For sexual excess?).

May I remind the reader that Jesus’ ministry only began because his cousin, John, was killed for speaking out against political corruption? That Jesus would be killed for speaking out against religious leaders who had allowed their religion to be hijacked by political forces? In the Gospels, Jesus is furious and destroys money tables and exchange centers inside the temple. Yet Paul encourages Christians to cozy up to the very system which threatens the authentic Christian message – economically, socially, politically.

Paul’s Jesus will forbid women from speaking about religious matters. When the Gospels recall Jesus routinely talking to women and choosing to speak to them first, immediately after he is resurrected from the dead. In fact, the resurrected Jesus will tell women to go and share the news of his return to those who should have been there with them – Jesus’ close friends, the apostles.

1 Corinthians 14:34-35

Women should remain silent in the churches. They are not allowed to speak, but must be in submission, as the law says. If they want to inquire about something, they should ask their own husbands at home; for it is disgraceful for a woman to speak in the church.

1 Timothy 2:8-14

I want the men everywhere to pray, lifting up holy hands without anger or disputing. I also want the women to dress modestly, with decency and propriety, adorning themselves, not with elaborate hairstyles or gold or pearls or expensive clothes, but with good deeds, appropriate for women who profess to worship God.

A woman should learn in quietness and full submission. I do not permit a woman to teach or to assume authority over a man; she must be quiet. For Adam was formed first, then Eve. And Adam was not the one deceived; it was the woman who was deceived and became a sinner.

But women will be saved through childbearing—if they continue in faith, love and holiness with propriety.

Ephesians 5:22-24, 33

Wives, submit yourselves to your own husbands as you do to the Lord. For the husband is the head of the wife as Christ is the head of the church, his body, of which he is the Savior. Now as the church submits to Christ, so also wives should submit to their husbands in everything… the wife must respect her husband.

This is not the same depiction of Jesus that the Gospels present. And it’s not that Paul’s instructions are immediately disgusting. In Ephesians, Paul spends more time addressing himself to husbands and explaining that men have a responsibility to be kind, generous, loving, and protective of the women in their lives. To be a “real man”, in other words, Paul says that men should care for others to find meaning and purpose, rather than making demands and using their physical strength and social privilege to harm and suppress. Selfishness, demands, anger, intemperance, these Paul holds up as behaviors to avoid. Instead, he writes, men should love the women in their lives “even as Christ loves the Church.” But, as noble as Paul’s instruction to men may be on paper, the fact remains that Paul’s treatment of women fails in the very same ways that he names men should make an effort to avoid. Paul’s Jesus, for example, is still a demanding one. Paul forbids women from speaking; if they must, they should do so privately, at home, behind closed doors. Paul’s theology of a generous salvation extended to all people… also notes that women will be saved through childbearing? The salvation of God is unconditional… except for women, who must obey their husbands in this life and will find salvation in the next life… but only “if they continue in faith, love and holiness with propriety.”

Paul’s definition of “the church” is male. Unreservedly so. Which runs contrary to all four Gospels and the non-Pauline Christian epistles, essays, theological discussions, and historical records. This is not even close. Paul’s ethic is not only different, it runs in direct contradiction to Jesus’ life, ministry, and death. Jesus, it seems, did not really understand salvation at all. It is unfortunate he misunderstood himself, his teachings, and the time that he lived in. If only he had lived long enough to listen to Paul.

Fourth, we have John “the Beloved” who presents a love ethic I want to return to momentarily.

Finally, in direct opposition to Paul’s teachings, we have “The Marys.”

Early Christianity is a bit spotty on the role of women. It seems Paul wanted women to be silent in the home as well as the church, but then he also mentions a number of women in his letters who are “fellow laborers.” It seems likely that, for all of Paul’s emphasis on right theology, he was willing to elevate women if they gave financial support to his travels around the Mediterranean. Women needed to buy status, and specifically buy it from Paul.

Jesus, the one depicted in the Gospels at least, seems keen to elevate the role of women. Like Paul, women fund his ministry, but unlike Paul, Jesus is frequently seen talking with (not to) women. He does not assume that they should “shut up” and “get back in the kitchen” like Paul does. He does not define women by who they are married to, whether they are married, or if they want to be married. He certainly does not make a connection between their ability to have children and their ability to (conditionally) earn salvation. Jesus’ attention to women is so regular that there are times where his followers seem amazed that Jesus would so publicly, so routinely, address women as equals. They even try to correct him, to ask him if he is aware of what he is doing and how much time and attention he is giving to women. After all, they imply, aren’t men more important? This is curious behavior on the part of Jesus, given the restrictive role Paul “properly” places women in one generation later.

Namely, we see Mary, Jesus’ mother, who is the most reliable source of information of Jesus’ formative life… erased. When Mary appears in the Gospels, Jesus dismisses her. She asks him to help at a wedding and Jesus yells at her, “Why is their problem somehow my problem?!” She tries to visit Jesus with his brothers while he is “on the road” with “the boys” (not his brothers) and Jesus asks, “Well, who is my mother and brother but the ones who are doing what I’m doing?” Like Peter. This account of Jesus is so bizarre that it even feels tucked away on the page. A fit of anger before Jesus walks off, never actually talking to her. Why is Jesus so angry and dismissive toward Mary, the woman “highly favored” by God? Then, later, we see Mary there at Jesus’ crucifixion. Apparently, she had been following him all along. Jesus’ trial and execution takes place in a matter of hours, not days, so it is clear that she not only was part of the caravan following him this whole time but close enough to the inner circle to have been there when Jesus was nailed to a post and hung up.

It’s strange, isn’t it, that Mary is there at the beginning, apparently is following Jesus around, and is there once again at the end, but we have no real record of her saying or doing anything. Jesus is depicted in such a way that it seems he is running away from her. One wonders why the editor of the Gospels allows Mary to be marginalized and silenced when she is a woman who was “highly favored” by God.

Turning to the next Mary, we see Mary of Bethany, the sister of Jesus’ friend Lazarus. It is conjecture, but many believe that Jesus and Lazarus grew up together. Whether this is true or not, Lazarus’ sisters Mary and Martha seem familiar with Jesus, as though he has been a frequent visitor to their home. Later writers will suggest that Jesus probably wasn’t married, but if he ever had been, he would have married Mary. She is seen listening to Jesus, even sitting at his feet, and some scholars indicate that the woman who anointed Jesus’ feet shortly before his death was this same woman – Mary of Bethesda, whose love for Jesus was remarkable enough to memorialize. If the crying woman who anoints Jesus is not Mary, that’s not problematic. In fact, it seems to confirm that Jesus was beloved by more women than his biographers can recall, those famous enough to be remembered by name and by those who time has forgotten.

The final Mary we want to consider is Mary Magdalene. This third Mary, the one of Magdala, has been depicted as the wife of Jesus in The Last Temptation of Christ; the novel by Nikos Kazantzakis was published in 1955 before being adapted to film by legendary director (and lifelong Catholic) Martin Scorcese in 1988. In the novel and film, Jesus has a fever dream of regret. About to die, he reconsiders his life and wonders what would have happened had he married Mary of Magdala, had chosen a different life of marriage and domestic responsibility. In Dan Brown’s novel The DaVinci Code (2003), Jesus and Mary of Magdala are actually married. They have children. They presumably live into old age in peace. Whether a dream of possibility, or a subnarrative in a detective novel, Jesus having a relationship with Mary of Magdala is an interesting theory, especially since Mary has been framed as a prostitute. People want Jesus to have an active sex life, I guess, and if he is going to have sex, then they want him to have a wife who (echem) can show him a good time. Maybe teach him a few things.

With so many women connected to the life, ministry, death, and post-mortem resurrected life of Jesus, a question emerges: where are the voices of women in the early Christian communities? Erased. Edited out. Suppressed. Forgotten. Marginalized. Relegated to the periphery of Paul’s letters; not even explicitly named, but instead defined by the men in their lives. Mary, Lazarus’ sister. Mary, Jesus’ mother. Mary, the prostitute, because apparently the only way a woman could have a little money is if she sold her body. Women, when they were noticed at all, are defined by men. By their marital status. By their willingness to spread their legs. By their ability to have children. By how many children they have. By whether those children are smart or wealthy or social climbers. Whether they are, like Peter’s mother-in-law, willing to get up “immediately” (notice an echo of Peter’s speed there) after suffering from an illness… to make food for The Men.

I’m not at all impressed by the erasure of women from the early Jesus communities. I suspect I am not alone in this, considering the exodus of women from churches whose denominations and leaders continue to preach that misogyny is the same as godliness.

I haven’t forgotten about John, but allow me to recap real quick.

Peter teaches by example. He shows certainty, even when he is (obviously) failing. James shows action and service, teaching “faith without works is dead.” Paul travels around, telling churches how they got it wrong but if they listen to him, they can have “right” theology, which pretty consistently just upholds the Roman way of life and makes bizarre philosophical claims. The Marys express too much love, are too emotional, and are willing to embrace the dead to give them dignity. So the Church tries to erase their memory but, in doing so, lays claim to the teachings that fit their male-centered narratives and theologies. Mary, Jesus’ mother, is useful only so long as she is virginal. Mary of Bethany is remembered for humiliating herself and wasting perfume (such a silly girl move). And Mary of Magdala? Thanks for the cash, whore. Go disappear somewhere.

Which leaves John, who emphasizes an ethic of love as the defining quality of the faith. John is not unlike the Marys in that his memory is washed away. He is either the self-professed “beloved disciple” in the Gospel bearing his name, or he is an enemy of the state, exiled to the prison colony on the isle of Patmos, spewing apocalyptic utterances and warning several churches that they will rot in Hell.

One wonders why John is so angry at these churches.