Something changed within Christianity after World War II. There were two ends of the spectrum for Christianity: on the one, historical Christianity experienced a revived optimism and intentional embrace of suffering through social programs. If Christ was going to return soon, Christians wanted to be the faithful servant who oversaw custodianship of the planet, the poor, and the hungry. Care for widows and orphans was tantamount to caring for Jesus Christ himself. Reform of prisons, orphanages, and the cold, remote detachment of the clergy were areas where Christians wanted to see growth and adaptation to the crises of their time. On the other end of the spectrum, apathy and civil religion had extended, or perhaps grown a new, albeit sickly branch. Evangelicalism, different from Christianity as it was presented in the Christian Scriptures, focused on the coming apocalypse and saw the flames of destruction as inevitable. What was the point of reforming society when Jesus would come back soon to destroy it all?

Instead of building God’s Kingdom on Earth, Evangelicals considered the fallenness of society, the erosion of nature, and found nothing that God had once declared “good.” Nothing here was worth saving, not even one another.

What was most important was that an individual have a “personal relationship” with Jesus, privatizing which after all was what Jesus had taught, right? Paul taught doctrinal truths about the wickedness of humanity and John assured believers that they would not endure the coming apocalypse anyway, safely “raptured” away to Heaven where the elect would have a front-row seat to a coming war where Jesus would destroy the nations. Evangelicals, with this view of the coming apocalypse, paid attention to the thrones they would inherit for enduring a world of misery. They were the elect because they loved Jesus more than the disposable Creation. They were the elect because they held the right doctrine and “understood the times”. The Earth was a resource to be mined and used up until the end of time, not something renewable or special. If the Earth was good, Evangelicals reasoned, then why hadn’t Jesus stayed? Surely, this was proof that Jesus and God had abandoned this terrible planet.

Then World War I erupted. Americans, who had imbibed both strands of Christianity, saw the realities of chemical warfare. Europe saw the indifference and reluctance of their leaders, understood – like their Medieval ancestors – that they were pawns in a family drama at best, a game of thrones at worst. Russians, enraged, threw off the chains of the ruling class. The Orthodox Church had remained silent and indifferent, cloistered away behind the screen of incense and chants. Religion, the Russians came to believe, was inadequate to the poverty and starvation that followed war. It was a sentiment shared by many, all over the world. In Russia, the masses went along with the promises of new leaders, ones who pledged to feed them, to share the world with them as comrades in a new society. They held on to a radical optimism like the kind American Christians held, only it was an optimism grounded on human effort instead of passive religion, the “opiate of the masses” according to Karl Marx, whose thinking was so important to Russia.

This optimistic utopia where humans restored one another and the Earth participated by generously meeting the needs of humanity, where flora and fauna alike celebrated the inauguration of new kingdom with peace, equality, and restorative justice reigning and righting never saw fulfillment. Instead, a new war erupted. This one in Germany, where the furious anger of people erupted and spilled over. After, saddled with debts they would never be able to pay, Germans met a hard winter and France, demanding reparations owed to them, began to seize firewood and coal – the only resources Germans had to endure the cold.

Germans began to realize they had been shackled by indifferent rulers. Their leaders had literally begged to stop World War I, had begged for the survival of their people, and the callousness of the French enslavers proved to be France’s undoing. Germans had been enslaved as the workers to this new undefined utopia and came to understand the conditions of surrender meant they would never be allowed a place in this utopia, never share in equality or peace.

If the world wanted a new reign and a new empire through their labor, so be it. Germany would give them a new kingdom, the Third Reich, which Adolf Hitler enthusiastically called out of the hardened German people. They would, like their Russian neighbors, throw off the bands that had enslaved them; only instead of destroying their leaders, they exile them. German lives were valuable, after all. Instead of upheaval and civil unrest, poverty and more hard winters enduring bureaucracy, Germans would destroy the secret powerbrokers, the betrayers, the secret enslavers who dwelled among them. They would, like Ezra in the Bible, route out those who profaned the heritage and genetic holiness of precious Germany, who had been abused for too long.

Ahistorical, blatantly racist, definitively nationalistic, the National Socialists captured the animosity Germany had toward France and redirected it to a new agenda. Jews, who had seeded the destruction of Russia before immigrating to Germany, were now living among them. Think of it! The pure-blooded and righteous German people! Denigrating their heritage by intermingling the purity of their race with profane Jewish blood! Jews had been given the levers of power and been secretly guiding Germans to destruction these many years and they must be plucked out and cast into the fires of industry to forge a new future.

It was, by any measure, a compelling narrative cobbled together with alternative facts.

In America, news of a secret state explained everything. German-Americans were hard workers, ready and able to meet the demands of their new home. They did not insist on reparations, like the French. They did not manipulate, like the Jews. They did not ignore the Church, like Russians. They did not await a day when they could turn their hands against their neighbor in the name of “justice” like the weak High Churches in New York and Boston with their so-called Social Gospel. German-Americans did not arrogantly proclaim they knew what was best for the lesser races and lower classes, like the self-professed Christians of America. Instead, they worked in factories and perfected them when they could. They held rallies and cultural celebrations. They showed up to work early. Left late. Gave a full day’s labor for a full day’s wage. They joined the local police and actually kept the peace rather than merely philosophizing on how to make peace. German-Americans were the embodiment of America’s ideal. The entire lebenswelt of Germany had moved to America and been celebrated here. Hitler’s own Mein Kampf credits America’s treatment of First Peoples and Africans with the racial policies he would employ upon his ascendency to power. Notably, when America entered World War II, they imprisoned Asian-Americans, not German-Americans. During the war, and even after, it was challenging for many Americans to see their German-American neighbors as enemies. Germans were good, hard-working people like themselves. Some Americans felt that German-Americans were not even “German” or that they should be hyphenated. Germans were Americans and, as many high school history books will imply even now, “real” Americans are of European descent. Americans during World War II felt that, on the whole, Germans were good people. They refused to fully believe the threats spewed forth by Adolf Hitler and the senior leaders of the Nazi Party to the very end, when photographic evidence, the Nuremberg Trials, and the reports of Allied Command produced incontrovertible evidence. Instead, conspiracy theories of forgeries (concocted by the Jewish media!) and exaggerated claims (by the lying Jews!) were allowed to moulder. Even those who finally believed in the genocide of the Jewish people were able to reason it away. There was a distinction to be made, after all, between “bad” Germans” who absolutely did not follow Hitler’s orders, my goodness. Betray the thought! These bad actors were lone wolves and renegades. This is, of course, assuming any of the reports were true. Who was to say? Lone wolves and bad actors were in charge of the camps, denigrating Hitler’s intent for a pure, glorious nation. There was no such thing as a policy of extermination. God forbid. But of course, all of this was assuming the reports were true. Who was to say?

Maybe genocide wasn’t the best way of going about it, but everyone knew that the Jewish people worked from the shadows to control governments, the media, and banking. That was more likely, more true, more verifiable, than acknowledging a culture of White Supremacy. One had only remember the sermons of Father Charles Coughlin, priest of the National Shrine of the Little Flower in Detroit, Michigan. Coughlin had warned the good people of America and Canada for years, hadn’t he? Father Coughlin had warned that Jews infiltrating America, bent on corrupting American (re: German) culture through movies, TV shows, books and art, before buying off American democracy through bribery, extortion, and malice. The only problem with Senator Joseph McCarthy’s so-called “Red Scare” was that it hadn’t been allowed to go far enough. McCarthy was on the cusp of exposing the Jews pulling the strings in the American government, expose the puppets who were subverting democracy and replacing it with ungodly Communism.

Clearly, manifestly, exhaustively, America was not well after World War II. Paranoia became normalized. Having defeated the German army, many Americans began to long for a simpler time where good and evil were less ambiguous. In the absence of a foreign enemy, Americans began to turn on one another. There was a tension slowly coiling tighter and tighter, even as Americans sought newer, fresher enemies.

In the coming decades, rock n’ roll would dominate the airwaves. Swaggart’s 1969 sermon album “The Ring of Fire” sums up his thoughts on this development.

You boys and girls that have Beatle records at home, this is the most rotten, dirty, damnable, filthy, putrid filth that this nation or the world has ever known. And you parents that would allow this filth to be in your home, you ought to be taken out somewhere and horsewhipped, you hear me? And I mean it, my friend.

Most Americans tired of the never-ending stream of witch hunts with McCarthy’s continued failure to deliver on his promise to expose a truth that never came about. Still, conspiracy theories persisted. The John Birch Society was founded in 1958 to expose communism and liberalism in American centers of influence, carrying over messaging about familiar “threats” in the wheelhouses of government, culture, and education. Increasingly, their members as much as the dubious publications they produced began to redirect the agenda of the National Rifle Association, whose original intention was promoting gun safety and responsibility. After the Birchers began to line the ranks of the NRA, the organization almost exclusively defended the right of Americans to have military-grade weapons with no restrictions. In one decade, the John Birch Society fueled a tremendous amount of violence. The Gun Control Act of 1968 was passed to try and mitigate the impact of the group, who cheered the assassinations of President John Kennedy (d. 1963), his brother Robert F. Kennedy (d. 1968), and Martin Luther King, Jr. (d. 1968). The resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan during the Seventies and the rise of a new threat – domestic terrorism – each have direction connections to John Birch Society and the conspiratorial ideas they circulated. Recognizing the threat, Congress passed legislation that would allow the reorganization of different pursuits together under one umbrella to better confront the radicalization taking place. In 1972, Department of Treasury investigator Rex was allowed to form the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives apart from the Internal Revenue Service. The overlap of each of the concerns involved here – firearms and weaponry, distribution of alcohol, cultivation and sale of illegal drugs, construction and distribution of explosives, financial crimes, legal loopholes, racist crimes and discriminatory practices, inability and negligence of law enforcement at all levels from local to federal – speak to an expanding recognition of the threat allowed to grow in America.

While Birchers were allowed to have radical views and express themselves freely, once they began to act on those views, the government had to step in. Federal Bureau of Investigation agents continued to notice connections between the crimes they were seeing and the connection many of the individuals they prosecuted had to the John Birch Society.

By the late Eighties, the organization was a breeding ground for illegal sale of weapons and racist organizations. Birchers have always, since their founding in 1958, been associated with ultraconservative, radical right, far-right, right-wing populist, and right-wing libertarian ideas. The society’s founder, businessman Robert W. Welch Jr. (1899–1985), developed an organizational infrastructure of nationwide chapters in December 1958 which allowed the group to flourish, much like the Ku Klux Klan’s infrastructure. In fact, the two were at times intertwined. The society rose quickly in membership and influence, and became known for Welch’s conspiracy theories such as his allegation that Republican president Dwight D. Eisenhower was a Communist agent, a view that was especially controversial considering Eisenhower’s strong anti-Socialist and anti-Communist views documented both abroad and later domestically. Still, the outgoing President’s Farewell Address on 17 January 1961 fueled Welch’s theories. There, President Eisenhower spoke of a nation in direct conflict with the one idealized by Birchers, White Supremacists, and other radical groups in America.

Throughout America’s adventure in free government, our basic purposes have been to keep the peace; to foster progress in human achievement, and to enhance liberty, dignity and integrity among people and among nations. To strive for less would be unworthy of a free and religious people… This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence – economic, political, even spiritual – is felt in every city, every state house, every office of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications… In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist. We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted.

The best evidence for Welch’s conspiracy theory was Eisenhower’s concluding thoughts.

We pray that peoples of all faiths, all races, all nations, may have their great human needs satisfied; that those now denied opportunity shall come to enjoy it to the full; that all who yearn for freedom may experience its spiritual blessings; that those who have freedom will understand, also, its heavy responsibilities; that all who are insensitive to the needs of others will learn charity; that the scourges of poverty, disease and ignorance will be made to disappear from the earth, and that, in the goodness of time, all peoples will come to live together in a peace guaranteed by the binding force of mutual respect and love.

Who the fuck did this bald dipshit of a former general think he was talking to? “Mutual respect and love”? “All faiths, all races, all nations”? Eisenhower sounded like a fucking Communist. This was America, not Maoist China. Good fucking riddance, “General.”

John F. Kennedy succeeded Eisenhower and it was no surprise that many, especially Birchers, rejoiced when Kennedy was assassinated in 1963. His agenda was picked up by Lyndon Johnson. When the replacement President ran for re-election in 1964, Johnson had an overwhelming victory. One so decisive, in fact, that

Lyndon Johnson and the Democrats had shattered the Republican Party. The greatest electoral margin ever given any party anywhere, 16,000,000 votes, had washed away every traditional Republican stronghold – the industrial Midwest as well as New England, the Plain states as well as the Rocky Mountain states. In the big cities, the Republican candidate, Barry Goldwater, had acarried less than 2 percent of the Negro vote; he had fared only sightly better among other ethnic minorities; he had lost the farmers, the old folks, the youth, wherever such interest groups could be picked out in the general pattern of voting. In Congress, Republicans faced the largest Democratic majority since Franklin D. Roosevelt’s zenith in 1936; in the Senate, they faced a hostile majority of two to one; across the country, they held only seventeen of the fifty governorships in the nation. Not since the Whigs had any great party eemed so completely to have lost touch with reality… No formal measurement can, however, give the particular odor of self-doubt, self-hate and defeat that stank in the corridors of the Party from top to bottom… No one in 1964 had even the vaguest idea of what might happen to the Republican Party four years later… Split in spirit, parochial, bound together only by tradition and emotion, the Republicans, a hideously wounded and scattered group of men, looked to the future, in 1965, with no greater common purpose than simple survival. (from The Making of a President 1968 by Theodore H. White)

Trying to place a bit back in the mouth of a wild horse, conservative William F. Buckley Jr. and his magazine, National Review, attempted to shun Birchers to the fringes of the American right. To some extent, Buckley and his fellow conservatives helped create an aspiration but never fully distanced themselves from the rancorous and fractured groups their party had splinted into.

Buckley knew the confederation of disparate groups within the Republican Party would need to be interdependent if they ever hoped to regain control of Washington after Nixon’s resignation for corruption, bribery, and obstruction of justice. Nothing could actually unite them, not even Buckley’s broad, undefined and undefinable aspirations, but the thinking was that they were family. Every family had its wild members. For Republicans, it was the conspiracy theorists of the John Birch Society. Or the racists of the South who may not have understood what Gross Domestic Product was, but hated Communists, niggers, and Jews along with “good” White people. Or the quiet nuclear family on the cul-de-sac who just wanted a school where their White children would appreciate their heritage or, to be more specific, avoid polluting their heritage with miscegnation.

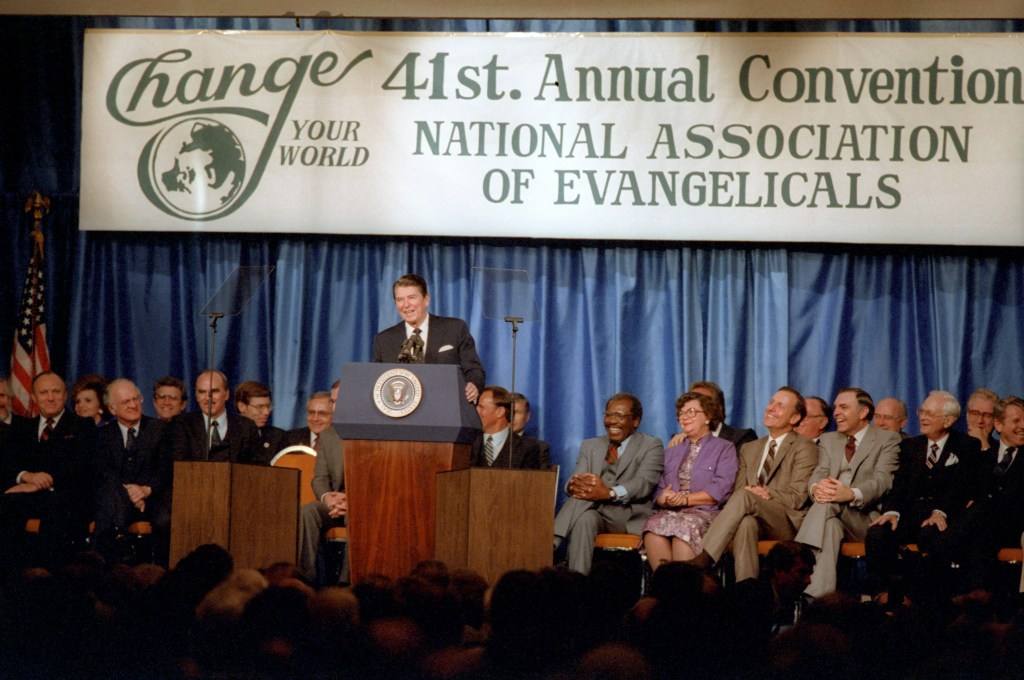

Time and experience had a way of repairing divisions, mending old hurts, and rewriting the details.The John Birch Society, like the Klan, kept membership private but their membership thrived under Democratic government and curiously began to decline when the Reagan Administration took office. It is not difficult to see the pattern. Reagan legitimized many of their views under a veneer of national pride. Reagan had promised to “make America great again” and followed through. Reagan gave these groups many of the “freedoms” they were seeking. Before the White House, Reagan had been governor of California. Before that, he had served as president of the Screen Actors Guild for two terms, from 1947 to 1952 and again from 1959 to 1960. He had worked diligently to route out Communism during the McCarthy Hearings. As Governor, he had crushed university protests. Oversaw the removal of restrictions for migrant workers and, as a result, an economic boom. California became an economic superpower unto itself. Once he became President, the United States provided overt and covert aid to anti-communist guerrillas and resistance movements in South America and the Middle East through the Reagan Doctrine. To the rest of the world, Reagan was a threat. He funded and armed the destabilization of countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. But, telegenic and the consummate actor, what most Americans saw was Reagan’s set jaw as he demanded Russia tear down the Berlin Wall. What they saw was him wagging his finger at Russian diplomats. It was consummate Anti-Communism. It was, in the eyes of most Americans, Pro-America. When gays mysteriously began dying from AIDS, Reagan refused to acknowledge their deaths. And here, if there were any holdouts, he began collecting the Hard Right. Hating Jews, Blacks, Communists, and gays was everything the Klan stood for and, remarkably, the Ku Klux Klan began to re-emerge under the leadership of David Duke, who was a calm and cool hater of “minorities” as much as a supporter of Republicanism, America, and Whites.

One would have to be blind to avoid seeing a connection here as the groups gelled around a new vision of American Empire. Reagan was seen as a champion for the Birchers, a unifier of the conspiracy theorists and mainstream Republicans. And Evangelicals. Decades later, former President Jimmy Carter would write in his Endangered Values (2005) that

Fundamentalists have become increasingly influential in both religion and government, and have managed to change the nuances and subtleties of historic debate into black-and-white rigidities and the personal derogation of those who dare to disagree… The influence of these various trends poses a threat to many of our nation’s historic customs and moral commitments, both in government and in houses of worship.

President Carter knew what he was referring to. He succeeded Lester Maddox as Governor of Georgia and lost his bid for reelection to Reagan in 1980, in large part because of Evangelical voters led by the Moral Majority under Rev. Jerry Falwell and televangelist Pat Robertson. And, of course, Jimmy Swaggart.

This divergent understanding of America as a White, Christian nation for heteronormative conservatism no longer remained in shady, clandestine meetings with ne’er-do-wells. It wasn’t explicitly violent. It had become civilized, mixed together with nationalist and racist attitudes. It sat happily and proudly in church pews, in arena revivals. It spilled over from talk radio to television, then premium television, then international broadcasting through satellite uplinks which exported a shared message of American values – White, Christian, heteronormative, conservative. This unified and unifying cult thrived under the wide umbrella of Republicanism, a myriad of different perspectives were allowed to thrive. Economic conservatives. The middle class, focused on “family values” and “traditional marriage.” Revisionists, editors of history willing to twist it into unrecognizable shapes to prove outrageous claims

One would like to imagine that these groups make for strange bedfellows, that the nuclear family who attend PTA meetings to develop a more competitive curriculum for their children’s school has nothing in common with the ham radio aficionado Vietnam veteran who refuses to see the “slant-eyed doctor” at the Veteran’s Affairs office. One would like to imagine that these households, dissimilar from one another, have nothing in common with the street evangelist condemning passersby to eternal damnation, or the bus driver who attends “cultural” rallies on weekends. The security guard at the sports arena who listens to talk radio because “they tell it like it is” instead of following “the liberal agenda.” The waitress attending the concert telling her friend, “I know it’s not politically correct” but it really is true that “Mexicans are stealing our jobs.” Each home, each individual, is unique and ensconced in the Constitutional promises of individual liberty, each one has chosen to live their life as they see fit. No two are alike.

We want to believe this because it feels like an American narrative, yet it is a fantasy. Republican strategists executed a long-term strategy of deciphering these differences, emphasizing common complaints as a source of unity but cultural identifiers – class, race, politics, religion – as sources of division. Writing for Politico in 2014, historian Randall Balmer focuses on a key figure in wedding these groups together in a fateful marriage of compromise.

In the decades following World War II, evangelicals, especially white evangelicals in the North, had drifted toward the Republican Party—inclined in that direction by general Cold War anxieties, vestigial suspicions of Catholicism and well-known evangelist Billy Graham’s very public friendship with Dwight Eisenhower and Richard Nixon. Despite these predilections, though, evangelicals had largely stayed out of the political arena, at least in any organized way. If he could change that, [Paul] Weyrich [the late religious conservative political activist and co-founder of the Heritage Foundation] reasoned, their large numbers would constitute a formidable voting bloc—one that he could easily marshal behind conservative causes.

“The new political philosophy must be defined by us [conservatives] in moral terms, packaged in non-religious language, and propagated throughout the country by our new coalition,” Weyrich wrote in the mid-1970s. “When political power is achieved, the moral majority will have the opportunity to re-create this great nation.” Weyrich believed that the political possibilities of such a coalition were unlimited. “The leadership, moral philosophy, and workable vehicle are at hand just waiting to be blended and activated,” he wrote. “If the moral majority acts, results could well exceed our wildest dreams.”

But this hypothetical “moral majority” needed a catalyst—a standard around which to rally. For nearly two decades, Weyrich, by his own account, had been trying out different issues, hoping one might pique evangelical interest: pornography, prayer in schools, the proposed Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution, even abortion. “I was trying to get these people interested in those issues and I utterly failed,” Weyrich recalled at a conference in 1990.

As Balmer explains, the catalyst was a case put before the Supreme Court in 1971, Green v. Connally.

The Green v. Connally ruling provided a necessary first step: It captured the attention of evangelical leaders, especially as the IRS began sending questionnaires to church-related “segregation academies,” including Falwell’s own Lynchburg Christian School, inquiring about their racial policies. Falwell was furious. “In some states,” he famously complained, “It’s easier to open a massage parlor than a Christian school.”

One such school, Bob Jones University—a fundamentalist college in Greenville, South Carolina—was especially obdurate. The IRS had sent its first letter to Bob Jones University in November 1970 to ascertain whether or not it discriminated on the basis of race. The school responded defiantly: It did not admit African Americans.

Although Bob Jones Jr., the school’s founder, argued that racial segregation was mandated by the Bible, Falwell and Weyrich quickly sought to shift the grounds of the debate, framing their opposition in terms of religious freedom rather than in defense of racial segregation.

It didn’t take much to get Evangelicals to agree to the legalization of institutional racism, to preach about it, to moralize it, to baptize it. After all, as theologian James H. Cone wrote in The Cross and the Lynching Tree (2011), “In the ‘lynching era,’ between 1880 to 1940, white Christians lynched nearly five thousand black men and women in a manner with obvious echoes of the Roman crucifixion of Jesus. Yet these ‘Christians’ did not see the irony or contradiction in their actions.”

The different groups were introduced and, finding common complaints and common enemies, began courting one another. They were still, in hundreds of ways, living apart. It took the fallout from President Richard Nixon’s involvement in the Watergate Scandal to weld Birchers, racists, and Evangelicals to the Republican Party, but welded they were. So much so that Evangelical leaders like Jerry Falwell and televangelists like Jim Bakker, James Robison, and Jimmy Swaggart managed to spread sufficient propaganda and Republican talking points in pulpits, podiums, sermons and daily calls to action that they managed to convince the American people that Jimmy Carter – a lifelong Southern Baptist who openly professed Jesus Christ as his personal savior, who a year before his campaign for President was knocking on doors asking people to accept Jesus as their own personal savior just like him, who witnessed poverty on the other side of those doors and humbly asked about their lives and how he could help, who expressed a deep commitment to racial reconciliation and international peace, who emphasized diplomacy instead of war – was not in fact a “real” Christian.

Ronald Reagan, a divorcee and occasional church-goer, was. Reluctant to discuss his personal faith, failing to meet the shibboleths of Evangelical culture, Reagan was still accepted as one of their own with no bona fides. In the end, the only proof Evangelicals needed was Reagan’s commitment to listen to their complaints. Tolerance of racism, conspiracy theories, revisionist history, refusal to accept the differences America had been founded on, the willful ignorance, Reagan’s silent acceptance of all of this told them everything they needed to know. He, like them, hated the same people. That was enough. The Christian Science Monitor summarized Reagan’s rhetoric as encouraging an arms race that “would someday, in logic, point toward war.” The author of the piece, Joseph C. Harsch, aptly titled his 26 April 1983 article expressing this fear “Are Russians Human?”. For Reagan, no. Russians were not human. They were members of an Evil Empire in a cultural war for global supremacy. Evangelicals took note of how Reagan’s rhetoric.

Decades earlier, Republicans had made Richard Nixon their scapegoat, directing attention to his illegal activities, his paranoia, and his log of secretive recordings. His obstruction of justice. The coverup he oversaw. The entire Watergate Scandal was, according to Republicans, the work of Richard Nixon alone. Time has revealed, curious as it may have been at the time, that Nixon had legitimate reasons for recording phone calls and meetings with even his staunchest supporters. He recognized that his fellow Republicans could not be trusted, that they would ultimately bring about his destruction.

What has been given less attention is the way that the Watergate recordings reveal a sinister side to the Republican Party as a whole, not just Nixon. The moral compromises they were willing to make. Mixed in with standard meetings Nixon took and the phone calls Nixon made are revealing insights into the party and how they could capture the “Dixiecrats” of the South, racists who still wanted America to do well economically. The tapes revealed how Nixon used religious figures, like his friend Billy Graham, to shield himself and his administration from accountability. It was revealed in 2002 that Graham, who had maintained an otherwise untainted reputation among American evangelists, held very strong views about the “stranglehold” that Jews had on America, one that needed “to be broken or the country’s going down the drain.” It was shockingly, unquestionably anti-Semitic and even Nixon expressed surprise at the evangelist’s remarks. Nevertheless, it was the residue of Graham’s friendship that helped restore Nixon’s public image years later. Nixon, raised a Quaker, was something of an oddity. Did he, like the Quakers of high school textbooks, wear all black and prefer horse-drawn carriages? Far from it. Hadn’t his religious beliefs – shouldn’t his religious beliefs – prevented him from the outright lies, manipulation, and criminality that Watergate had exposed? In his long political career, Nixon’s inability to properly explain his religion except in contrast to JFK’s New England Roman Catholicism was a gap in the resume. Christians were willing to support him, but only as a tool. Nixon had been Eisenhower’s Vice-Preisdent. Yet Eisenhower had hated him. It is a math game perfect for armchair historians. Eisenhower had shown himself soft and incapable to the Birchers, and his dislike of Nixon might be the tell. Perhaps Nixon, riddled with paranoia and distrust, with his evasive personality and the protection given him by those around him might prove a compromise that could reunite the Party with the engines of anger and frustration necessary for a calculated win.

History is, ultimately, the study of people and the choices they made. What would happen, Weyrich wondered, if Evangelicals could be weaponized toward political ends? What future might leap out from the forge?

Swaggart remained a hostile critic of Carter until his death at the end of 2024. Like many Far Right members, Swaggart lamented the death of a godly man. Swaggart, like his fellow Christian Nationalists, fellow Republicans, fellow members of the Far Right, had always had a way of revising the past to suit his rhetorical needs. The argument that Jimmy Carter was a good man but a bad President is further proof of the compartmentalization required to justify all manner of evil in the name of God. That Carter was a good man but bad President – admittedly, quite possible – was an almost liturgical response to the mere mention of his name. It was required to justify what followed, the way Evangelicals refused to acknowledge Carter’s faith as much as the way Evangelicals compromised their own. It is a position worth challenging, worth questioning where this script came from. The idea was largely a product of Reagan supporters, among them Boomer parents, principals, and pastors. Carter was only a bad President if Reagan was a good one. No mention is ever made in this assessment of Carter whether his administration was consequential. Carter’s “badness”, his “failures” plural as a President, are predicated on the denigration of diplomacy instead of violence, Carter’s focus on long-term energy solutions instead of quick fixes, Carter’s resistance and at times dismissal of powerbrokers on Wall Street and in Washington, D.C., including his resistance to the status quo of his own party, as shown by his confrontations with Democratic House Speaker Tip O’Neil. Carter was a bad President for Evangelicals because he was a bad President for the establishment. Ronald Reagan became the diametric opposite of everything Carter stood for. As soon as he entered the White House, Reagan ordered the removal of solar panels on the White House and ordered his aides to turn the thermostat down. Reagan’s courting of Evangelicals, allowing them the proximity to power, legitimized the divisiveness they celebrated. It legitimized a worldview based on apocalyptic thinking, the anticipation of global war and welcoming of it as proof that Jesus would return to divide the world into the good people, who would, of course, be rewarded for their free market trickle-down economic policies (“Voodoo economics”, according to Reagan’s Vice-President George Bush when they were campaigning against one another) and Anti-Communist politics, and sinners who would of course burn forever and ever and ever because they were too fucking stupid to understand that Jesus was White, voted Republican, and loved America.

In the 2010s and 2020s, several observers, commentators, authors, retired law enforcement, active law enforcement, officials and administrators, joined one another in a rising chorus that while the John Birch Society’s influence peaked in the 1970s, “Bircherism” and its legacy of conspiracy theories began making a resurgence in the mid-2010s and had become the dominant strain in the conservative movement. As former FBI informant Joe Moore explains in White Robes and Broken Badges (2024), hate groups and far-right spinoffs, Nazis under new names, infiltrated local politics and law. Police officers, poll workers, school boards, all parts of “an Invisible Empire” at work. Churches became a hotbed of Far Right ideologies, particularly in the South, Midwest, and Northwest. The 1992 Ruby Ridge Standoff in Ruby Ridge, Idaho, was the most famous example because in this one event so many groups began to intersect.

Under Democratic President Bill Clinton, Republicans began to forge new unions. Far Right radio programs like The Rush Limbaugh Show allowed listeners to call in and express their frustrations with the nameless, faceless liberals, Communists, and Socialists destroying America. There was no distinction or differentiation between political ideologies

Birchers re-emerged again and again in the following decades by way of racist posts and memes in Internet chatrooms, the enthusiastic audience of Far Right radio programs like The Rush Limbaugh Show, The Tea Party, the Christian Right, and the Trump administration. The cesspool of deplorables slowly began to infect the broader conservative movement under the cover of social acceptance by way of the Republican Party. And the audience of Jimmy Swaggart, who was one of, and then the most popular radio and television minister throughout the Seventies and Eighties.

One thought on “Biography: Jimmy Swaggart, Chapter 9”