In 1958, Jimmy quit his job to go into full-time ministry as an evangelist. One cannot help but observe the rootlessness of his early adulthood, the abandonment of his parents toward him and his sister for a higher purpose. As an evangelist, he is “called” to travel and, by definition, homeless. The life of an itinerant minister, an evangelist, in Pentecostalism is one without the oversight of a “home” church or even a denomination. His first effort to join the Assemblies of God was met with failure. The denomination expressed confusion at his application. Was Jimmy a singer? A minister? His “ministry” as an “evangelist” consisted of a handful of sermons, often about a coming judgement concluding in an awkward altar call. And an accordion. The piano would come later.

The Assemblies of God denied his application. Donnie was now four years old. Frances was twenty-one. She and Jimmy had been married for six years, and their life was decidedly worse than it was when they had gotten married. But Jimmy was “called” wasn’t he? Hadn’t that been the story since he was a child?

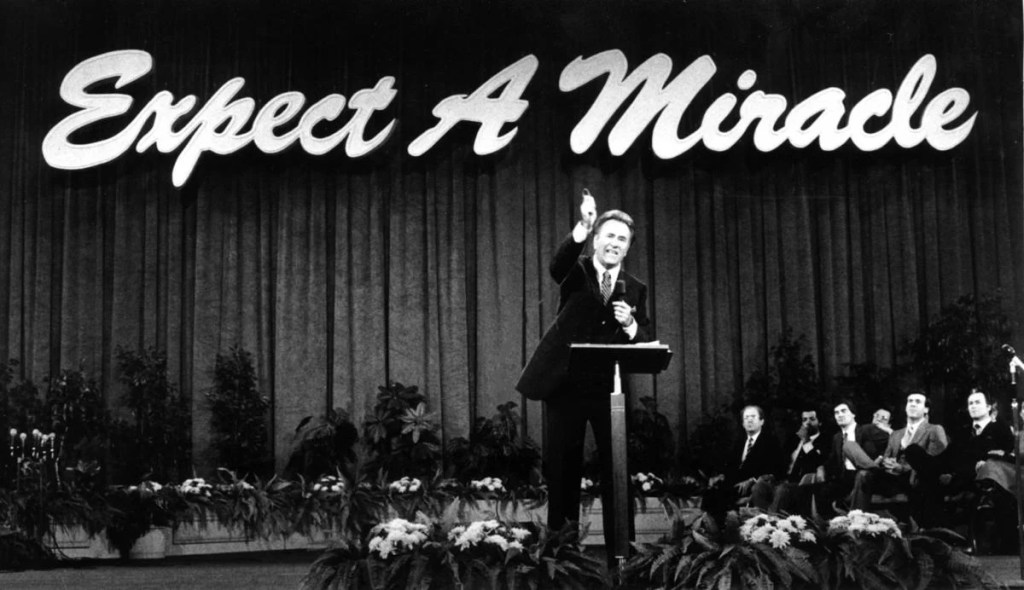

The denomination had spent over five decades polishing their reputation as pew-jumping snake handlers. The success of other evangelists like Oral Roberts, whose tent crusades and healing ministry were known throughout the country, had not given Pentecostalism the social currency, acceptance, or legitimacy they aspired to. Instead, it had put the most bizarre aspects of Pentecostalism on display under a circus tent. Evangelists and revivalists who returned from World War II peddling miracles were seen as hucksters and shysters, con-men who sold snake oil and splinters from the cross Jesus had been crucified on. Even “successful” ministers like Oral Roberts, who claimed divine power to heal and perform miracles, still played to a specific kind of audience – the desperate, the illiterate, the downtrodden not quite able to overcome the long effects of the Great Depression. Apart from his cattle stall “healing lines”, Roberts’ sermons were optimistic, an explicitly different approach to sermonic discourse. Roberts and the more recognizable Norman Vincent Peale, a radio minister and author, popularized the use of positive thinking in Evangelicalism. Roberts and Peale approached ministry as an expression of God’s love, salvation the ultimate form of uplifting the believer into a new and heavenly life, the “Holy Spirit” as an inward witness to the blessing and joy of God. Both promised financial “blessings”, the “restoration” of relationships, and “abundant” spiritual “increase” to those who donated to their ministry or “simply believed.” Where they diverge is their consideration of these donations. Peale, pastor of Marble Collegiate Church in New York City, had a stable “home” church who paid him a salary, provided health insurance, and a living stipend. Roberts, a traveling tent revivalist, was less financially secure. He and his ministry were, legally and financially, the same entity. Roberts, more than Peale, had to navigate the constant request for financial support, offering vials of anointing oil and prayer cloths to incentivize giving.

He went a step further, developing another teaching, this one on “the principle of seed faith”, where he declared that God had revealed to him the “laws of seedtime and harvest.” Essentially, a believer would “sow” (or donate money) to a ministry and they were “promised a hundred-fold return”. Roberts grounded this revelation in Genesis 8:22, which says says that “As long as the earth endures, seedtime and harvest, cold and heat, summer and winter, day and night shall not cease.” Roberts often omitted the other parts of the verse, the bits about cold and heat, summer and winter, day and night. Selective reading of scripture, also known as proof-texting or cherry-picking, frequently leads to a biased or incomplete understanding of the Bible. This can happen when someone chooses to only read verses that support their own viewpoint, while ignoring verses that contradict or qualify their interpretation. But it worked. Those who attended his healing crusades donated all they could to something like a heavenly casino, assured that eventually God would pour out riches of abundance on them so long as they continued to “sow” into Oral Roberts’ ministry.

Along with seed faith, Roberts developed a new “principle”, this one of the abundant life, often incorrectly grouped together by religious historians and sociologists who study televangelism and the impact of media on religious communities. Together with the “eternals laws” of sowing a reaping, Roberts offered a more palatable message of blessing beyond the financial promises of seed faith. The teaching of “abundant life”, or a supernatural life with blessings in the form of physical health, relaitonal strength, and financial prosperity emerged when Roberts transferred his ordination from the Pentecostal Holiness Church to the United Methodist Church in 1968. He had originally been ordained by the PHC in 1936, but once he left the plains of Oklahoma for a television ministry, and especially once he became a celebrity, the no longer embraced him as one of their own. To the Pentecostal Holiness believer, Roberts offered another “gospel”, one no longer focused on salvation and the instruction from God’s Spirit in this life on how to endure constant suffering (with relief from suffering in the afterlife and judgement against those who caused the suffering), but instead one that was “worldly” and thus apostate from the True Gospel that they claimed to possess. Methodists offered Oral something of a rebrand. As the Pentecostal Holiness Church distanced themselves from him for apostasy and worldliness, Oral was able to reposition himself and his ministry – now organized as the Oral Roberts Evangelistic Association to welcome the inclusion of ministers (and financial donors!) who shared his views – as part of the America experience, tracing his theological inheritance to Early America. Nothing was more American than an abundant life.

Still, Roberts attracted his share of critics. He had received a great deal of bad press from journalists and wary pastors in the areas where he set up his tents to minister. These critics began to call Roberts a huckster, a flim-flam man who sold trinkets and accoutrements like prayer cloths and vials of anointing oil – what Roberts called “points of contact” with his ability to perform miracles and heal people – that never healed people, never delivered miracles, but were still advertised as miracle cures for whatever ailed the ignorant, the desperate, the destitute, or more likely, the outright idiot. Roberts shrugged off his critics, insisting that they had it right – the “prsoperity gospel” they made fun of was just that. A gospel of prosperity. He thanked them for their criticism, believing that any press was good press. He welcomed the believer along with the questioning and the critics. His positivity and cheerfulness in the face of unrelenting criticism was proof, Roberts claimed, that he relied on God instead of himself. God’s reputation was on the line, not his own. That was proof of his love, devotion, and faith in God.

Local ministers, overseeing congregations of twenty to fifty members – all of whom were already related – could only offer the kind of small-minded mentality and theology that Roberts wanted to leave behind. As his ministry continued to grow, pastors and even other evangelists denounced Roberts and did their best to show that his message of an “abundant life” was not to be found in the pages of scripture, even if what Roberts promised sounded welcoming. His healing ministry, they pointed out, did not restore limbs to those who lost them in the war. No one was cured of polio. Although Roberts claimed to restore sight to the blind or even bring people back from the dead, most of the “miracles” that took place in his healing lines were of the common cold – and even then “healing” would come several days later after the illness had naturally run its course. If Roberts had actually restored sight to the blind, healed people with missing limbs, or done any of the things he claimed, where were they? Did he know their names, where they lived, or was he able to produce any information about them? Surely, there was a follow-up from his ministry with miracles like the ones he claimed to have produced. A mailer, perhaps, saying “Just checking in on your new eyeball” or offering to return the wheelchair they left behind when they were able to walk again.

Roberts seemed unable to produce anyone, anywhere, at any time with a testimony of these things. There were no doctors who stepped forward to verify his claims, no ministers who could confirm that the paraplegic had attended their church and returned the following Sunday able to walk after attending a healing line with Oral Robrts. He was never able to produce family members or friends, coworkers, anyone who could corroborate the claims that he made. And it was curious, wasn’t it, that Roberts had a magazine, a mailing list where he made these claims routinely, a broad base of supporters across the country, but never produced interviews with witnesses, the healed, doctors, or local ministers. In 1954, Roberts became a televangelist to share images from these services. The Abundant Life, his television program, would eventually become something like a variety show with music and short interviews where guests cheered Roberts on and expressed that the “law of seed faith” and the “abundant life” were real. But again, no witnesses. No one who said, “I was born without an eye and as you can see yourself, I now have one” or “Here is a photo of me in the hospital after Normandy, here is another photo of my wounds. And as you can see, I am healed.” No one went on the air with him to chat and give a testimony. Salvation, healing, how to become more holy, how to become a better marriage partner, how to live a Christian life all took secondary emphasis to the “abundance” of God and the “blessings” of God’s favor. The only “miracles” he provided or testimonies shown were someone who worked hard and donated to the Oral Roberts Evangelistic Association, then got a raise. A woman who had wanted to get married, sent a check to Oral Roberts, and eventually got married. An elderly individual who prayed for their child, sent money to Oral Roberts, and their child called them on their birthday. It was clear that the “law” of seedtime and harvest was the core around which his ministry continued to expand. Were these miracles? Perhaps to the individual, but not the kind Roberts promised and certainly not the kind described in scripture. The never-ending and increasingly outrageous claims never seemed to stop. In fact, they became a defining quality of his ministry. In 1987, the United Methodist Church finally revoked Roberts’ ordination after he claimed to raise people from the dead. It didn’t help things when he claimed that he had written a book titled “How I Learned Jesus Was Not Poor” and detailed how Jesus had “sown” his life with dead to be “harvested” into a life of abundance and riches in Heaven, a shocking and unsettling way to interpret the central message of Christianity. It also did not help when Oral, facing financial insolvency with the construction of his university, described a vision he claimed to have had of a ten-story tall Jesus looming over the campus of Oral Roberts University in Tulsa, demanding that Oral’s supporters send $10 million dollars immediately or God, Jesus, somebody, would kill the minister. The outrage over his claims now spilled over and many networks stopped airing his program. Naturally, Oral blamed other Christians for not having the faith to believe him. As for the $10 million ransom God demanded, a racetrack gambler paid it to prove that Jesus was, in fact, quite poor. What kind of savior would hold a senile old man like Oral Roberts for ransom, anyway?

To date, no death certificate or autopsy has been produced to verify Roberts’ claims of raising the dead.

To date, no living person has verified Roberts’ claims of missing eyes or limbs miraculously growing back after a “point of contact” with Roberts through the laying on hands, prayer clothes, anointing oil, touching their television screen, or even in answer to Roberts’ prayers.

To date, no ten-story tall person, least of all Jesus – whether living, dead, or resurrected – has ever stepped forward to admit they held Roberts for ransom.

Instead, at Oral Roberts’ funeral in 2009, his son Richard Roberts asked for those in attendance to donate to the Oral Roberts Evangelistic Association. He needed money to pay outstanding legal fees. By then, Richard Roberts had been found guilty of tax evasion, misappropriation of funds, fraud, and other financial crimes during his oversight of the ministry. He was removed as President of Oral Roberts University in 2007. His wife, Lindsey, famously turned on their audiences for criticizing the family’s misuse of ministry funds. Friend Suzanne Hinn joined them, declaring many Christians needed “a Holy Spirit enema.” Eventually, the board resigned in humiliation for their decades-long negligence.

Oral Roberts, more closely aligned with Swaggart as a fellow Pentecostal and a contemporary in the expansion of television ministries, was not the only one promoting a gospel of success and an abundant life. Kenneth Hagin, another minister in Oklahoma, was a student of E.W. Kenyon and also taught possibility thinking or what would become known as the “word of faith” where a believer, as a divine being, would speak things into existence as God did in the book of Genesis. Roberts, Hagin and then Hagin’s son, Kennth E. Hagin Jr., would inspire other ministers to teach similar things about the power of words and the inherent power of humans to re-order the world through positive speech and thought. These teachings came about, curiously, around the same time in a post-World War II America.

Kenyon, for his part in this emerging bloc of Pentecostal-adjacent “non-denominatonal” did not emphasize the power of confession but inherent godhood, apart from the salvation experience. This emerging strand, “Charismatics”, emphasized miracles and divine power as a dormant power activated by salvation or, more accurately, “liberation” of the mind. Traditional religion, Charismatics claimed, was antagonistic toward these “eternal truths” and refused to acknowledge the goodness of God and humans who were created in the image of God. The power of confession was a revealed truth, not explicitly named in scripture but evident to those who had “eyes to see” and “ears to hear.” They relied on Jesus’ offhand comment in the Gospel of John 10:34, “Is it not written in your law, I said, Ye are gods?” In context, Jesus said this in response to an accusation of blasphemy and was quoting Psalm 82:6, which says, “I have said, Ye are gods; and all of you are children of the most High”. For Charistmatics, those with eyes to see and ears to hear could piece these proof-texts together to understand a “revealed truth” that all humans were children of God, endued with power by birth and not salvation. It was not Kenyon’s most controversial teaching, however. Kenyon also taught that Jesus was not unique. While various councils and creeds of the Christian church has historically emphasized Jesus as both God and human, Kenyon pointed out that with Psalm 82 and John 10 in mind, all humans shared this dual godhood-humanity. Further, contradicting the Bible and dismissing the historical claims of the Church regarding Jesus’ sinlessness, Kenyon continually wrote and spoke about Jesus as one who was fully infused with sin after his death. Kenyon, and eventually those who subscribed to his teachings, would point out to the Apostle Paul who wrote in II Corinthians 5:21 that “[God] made [Jesus] to be sin who knew no sin, so that in [Jesus] we might become the righteousness of God.” If there was anyone who doubted the inherent goodness of humanity, Kenyon noted, Paul claimed God had proven once and for all that the believer was righteous and had been ever since 33 A.D.

Jesus, according to Kenyon, was a victim of Satan and various other demons. The salvation message that Paul described in his epistles (encapsulted in I Corinthians 15: 3-8) did not go far enough. The authors of the Gospels – Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John – were shortsighted in their understanding. They meant well, but they did not really understand Jesus. The believer, while depending on the Gospels, was not beholden to them any more than Jesus ever was – which is to say, not at all.

It is implied at times by Kenyon that even Jesus did not fully understand his role in the theater of God. Jesus, Kenyon writes in The Hidden Man (1888), was a victim of misunderstanding. God hid things from Jesus so that he would go through with the crucifixion, so as not avoid his destiny as “a Satanic being.” By the end, Jesus was not only a victim of misunderstanding, a victim to God’s deception, he was also a victim of Satan and other demons until he received a new revelation in Hell. One that Kenyon had and, thank goodness, which was available to every believer. Salvation was not possible until someone finally “got it”, and Jesus just so happened to be the first person who finally did. Kenyon writes,

///

Jesus first suffered in the arms of the Devil and until man was justified and salvation was available, and when the punishment for man was satisfactory to the Father, God liberated Him and that’s when He butchered Satan and his Demons.

This is what Roman 4:25 declares “Who was delivered (to Satan) for our offences, and was raised again (liberated from death) for our justification.”

2 Corinthian 5:21 “For he hath made him to be sin for us, who knew no sin; that we might be made the righteousness of God in him.”

Jesus identified himself with the human race and became sin, “a Satanic being” so that we may be what makes God right.

///

He goes on to explain that Satan and the demons (all of whom were once angels) grew frustrated at God bestowing humans with godhood. Why were they, God’s attendants, not born as gods like humans, who were new to the created order? Demons were frustrated not because humans were necessarily better, but because they shared fellowship with God – like the Gospel writers had with Jesus – but never fully understood their own power.

///

Righteousness means fellowship with the Father.

Righteousness is the authority and power that man and God share.

Righteousness is what Adam lost when he hid from God in the garden after sinning.

Righteousness is what Jesus lost when He was made sin and He cried “My God, My God, why have you separated yourself from me?”

Righteousness is what makes a man reign like a King in life over Satan. Satan by nature is a coward, of inferiority fear, full of inferiority complex, primitive in character, uncreative, destructive, full of poverty mentality, weak in nature, full of sense of lack, he is dirty and he stinky, selfish, and he fears and hates Christians who know that they are the righteousness of God in Christ because righteousness means power and authority.

///

There are observable parallels here to attitudes that would finally come to the forefront with the Cold War. Demons, like the Russians or even the Nazis, weren’t bad people. They just didn’t realize their power. In the heavenly realm, there was a race toward power and it was the same race taking place here on Earth. The Church, Kenyon pointed out, praised Satan and honored him by focusing on lack, on sin, on seeking a salvation that was already given instead of allowing themselves to receive a new revelation of power, authority, and might.

///

All the great praise we hear about Satan is from ignorant believers who have never taken their place in Christ. They believe the teachings from demons rather than the Eternal Word of the Father.

///

The Church, according to Kenyon, needed to stop preaching about sin and salvation. Instead, they should emphasize the inherent goodness of humanity. Call it mind science, call it positive confession, call it the elimination of self-doubt and criticism, whatever you wished. The believer needed to realize the inner power they possessed, believe in themselves, and speak with power from a position of authority. Fear and doubt were the real sin, the one which continued to hurt Jesus millenia after his revelation in Hell.

It was no surprise that the Church had been fooled long ago and had been teaching false doctrine for centuries. Even Jesus had been defeated by the lies and deception of Satan (or was it God?). It had been this way since Adam and Eve, whose “sin” – if it could even be called that – was not eating the fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil (an idea that would be more in alignment with Kenyon’s teachings) but instead believing Satan’s lie that humans were less than God.

///

When Adam sinned he became as fearful as the devil and hid from God.

///

Jesus’ resurrection proved humans were divine; after all, Jesus had resurrected himself once he got tired of Satan. Jesus’ salvation of himself came about once he recognized he did not have to live a life of abuse and poverty, but that He had always been divine. America’s success, Kenyon prophesied, would become apparent when they stopped focusing on sin and began focusing on their power.

///

Countries that have rejected God and suppressed the Gospel and have let Satan reign over them are full of the primitiveness, poverty, war, corruption, murder. Destruction is their law. Non-Christian people are not creative or inventive, they need no copyright law, they always imitate. Look at Arabia, Africa before the Gospel was taken there, India, Pakistan, Iraq, These countries are full of turmoil and deaths of the highest records are reported from these countries. Africa was liberated by the Gospel, so was Europe, Anglo-Saxon, and America… The Christian is God’s authority on Earth because he is the righteousness of God. When we understand the word, we take the place that God planned for us before the creation of the world. Satan knows he is defeated. All heaven knows he is defeated. And yet the church looks upon him as a Master (from The Hidden Man: Two Kinds of Life and Two Kinds of Righteousness [1888]).

///

Norman Vincent Peale’s ministry in New York at Marble Collegiate Church may have expressed the teachings of Kenyon in a different way, absent the revelations in Hell and maliciousness of God, but all of the points of emphasis regarding positivity and belief in self are certainly there.

Humans are inherently good, Peale claimed, not sinful. The Church had erred (even, at times gone astray or “sinned”) by emphasizing sin instead of goodness. They called an oppressive message of sin “salvation” and their own goodness a “lie”. Satan was a deceiver, more comfortable in the pulpit than in the slums and backalleys of New York. What Christians needed most was to believe in themselves, in their success, and speak it out. This reordering would bring about the Kingdom of God.

More than anything, America was a Christian nation. And Christians needed to believe in their country to avoid becoming like third-world nations like Arabia, Africa, India, Pakistan, and Iraq. They needed to reclaim the message of inherent righteousness, their own individual righteousness, and embody God’s authority on Earth. This is how the Christian could make America great. The first chapter in his self-help manual, The Power of Positive Thinking was “Believe in Yourself” before going on to explain in subsequent chapters how the Christian could create their own happiness by embracing themselves (sins and all!), to simply not believe in their defeat whether on the job, at home, or politically. The life of the Christian had been held down for too long by well-meaning churches. What the Christian needed now was an “inflow of new thoughts” to remake them (chapter 13), power to solve their own problems (chapter 10) and “create your own happiness” (chapter 5) apart from the teachings of the Church. The Christian – by which Peale meant everyone, not just the deceived who still insisted on being “saved” – to draw upon a higher power (chapter 17). Because people liked success (chapter 15), so Christians, everyone, needed to “stop fuming and fretting” (chapter 6) to instead “Expect the Best and Get It” (chapter 7).

Peale’s approach single-handedly pioneered the Christian self-help genre. Like Oral Roberts, he insisted on optimism and beleving for the best. Unlike Roberts, the locus of control was not faith in God but faith in self. At times, Kenyon’s writing and sermons can be held up alongside Peale’s with evident indebtedness to Kenyon. Both ministers were, at least initially, aligned with the Methodists. Both ministers expressed frustration with the limits of the Church and both ministers broadly insisted on a more philosophical approach to life in their sermons and writings. Both also failed in terms of giving practical application to their audiences, the very thing that they both condemned in the Church.

Peale’s views were more humanistic, less anchored in scriptural proof-texting and, unlike Kenyon, there was at least an attempt to conclude a thought before developing another one. Kenyon’s writings often raise more questions and show evidence that he had not fully thought through what he was saying. Satan had been in control of the Christian church since it was founded? Jesus was a victim of Satan, God, circumstance, demons, anxiety and self-doubt, as well as other Christians? If anything, the Gospels suggest that Jesus was a “victim” of empire and religious zeal, not these other concerns. And how could Jesus have been a victim of Christians, when Christians did not exist until after his death? As for that bit about Jesus saving himself? It’s strange, to put it mildly. The unweildiness of his teachings falls apart quite easily, at times directly opposing scripture as well as the traditions and teachings of the Church. What comes through is a blatant ignorance, even resistance to critical thinking, and a very poor familiarity with the Bible as he shows an inability to select relevant verses and place others into even a loose context. He picks up a thought and ends it with a verse of scripture that has nothing to do with the matter at hand, offering no liminal connection to sustain his arguments and poor use of logos, or appeal to scripture, to support his thinking.

Peale, in contrast, relies on ethos, the social currency/authority of his position as a minister, without scripture or best practices. With the success of The Power of Positive Thinking (1952), Peale did what many ministers tend to do. He began to speak about politics. Despite arguing at times against involvement of clergy in politics, Peale had some controversial affiliations with politically active organizations. He opposed Adlai Stevenson’s candidacy for President because the candidate was divorced, which led Stevenson to famously quip, “I find Saint Paul appealing and Saint Peale appalling.” Later, Peale led a group opposing the election of John F. Kennedy for President, writing for Newsweek, “Faced with the election of a Catholic, our culture is at stake” (19 Sept. 1960). Respected theologian Reinhold Niebuhr responded to Peale in the same issue, saying Peale was motivated by “blind prejudice.” Peale received intense public criticism, especially from Catholics in Boston, where he had attended seminary at the Boston University’s School of Theology, and from Catholics and other groups in New York, where he pastored. As a result, he reluctantly retracted his statement and began developing a friendship with Kennedy’s opponent, Richard Nixon.

Peale’s theology was appealing to many Americans with its emphasis on Americanism, self-reliance, hard work, and positivity. Among theologians, it was controversial. Prominent (and actual) theologians such as Ronald Niebuhr and William Miller spoke out publicly against Peale’s popularity. They contended that Peale’s theology falsely represented Christianity and that his writings and sermons were factually false, at times remarkably detached from scripture, tradition, reason, and experience. Raised as a Methodist, Peale should have been familiar with these. Peale, however, had set aside his affiliation with the Methodist Church when he was offered the pastorate of Marble Collegiate in New York, which was part of the Reformed tradition in America. Even more cause for suspicion, Niebuhr and Miller claimed. The Reformed tradition put primacy on scripture, tradition, and reason. In a 1955 interview with William Peters for Redbook, Niebuhr said “This new cult is dangerous. Anything which corrupts the Gospel hurts Christianity. And it hurts people too.” William Miller wrote that Peale’s theology, so critical of the Church that it veered into the ahistorical, was “hard on the truth” and full of undocumented claims.

None of this prevented or even inhibited Peale’s popularity. In some ways, his ability to set aside the Bible for a message of success, likeability, positivity, and self-help was part of a larger movement within Evangelicalism toward Americanism. The greatest contribution Evangelicalism has ever made is not the zeal for righteous living or damnation of evil in society that defined them in early America, but the erosion of history and the rejection of scripture that took place in the middle of the Twentieth Century. Both were replaced by zealous Americanism and corrosive White Nationalism that prevails over every other area of religious life, masquerading for decades as “faithfulness” to scripture and “eternal truths.”

Peale would inspire other ministers cut from similar cloth. Robert H. Schueller founded the Crystal Cathedral in Garden Grove, California. Schuller would write similar books and deliver similar sermons, emphasizing the goodness of people and the joy to be found in optimistic, positive thinking. When Schuller’s son, Robert A., assumed the pastorate of his father’s church in 2005, he began preaching in the Reformed tradition of sin and salvation. His father, the elder Robert H. Schuller quickly removed his son, explaining, “I was called to start a mission, not a church. You don’t try to preach… what is sin and what isn’t sin.” It was an approach to “ministry” very much in line with his predecessor, Norman Vincent Peale.

Even Billy Graham credited Peale with helping him better recognize the importance of a positive sermon. Graham began changing the delivery and content of his sermons some time in the 1960s, during the Civil Rights Era. His early sermons, which named Russia and Communism as a terrible evil, which emphasized the wickedness of his audience, began to emphasize the goodness of people as the minister took on a more ecumenical approach and softening of the Gospel. Graham, along with many other Evangelicals, chose to sit out the Civil Rights Era. He did not address racism in the streets, churches, and institutions of America. Graham’s reluctance to address the most pressing social issue of his time, or any issue other than political conservatism. Graham’s firey sermons, and now his hollow attempts at ecumenical compassion, often condemned Communism embedded in American offices and highlighted the importance of voting for godly (Protestant) candidates. Certainly not a Catholic like John F. Kennedy, whose “un-American” religion obligated him to be a puppet for the Pope. Graham insisted he was apolitical, even as he encouraged loyalty to America. He was disinclined to march or protest for the rights of Blacks, who made up more than a third of the American population. His reluctance to help, to even stand up for anything beyond his own White Republican Nationalism, brought increasing frustration and disappointment from fellow ministers like Martin Luther King. And the young traveling evangelist Jimmy Swaggart, who “hated” Graham’s rallies and “crusades” which softened the Gospel into an emotional and individual salvation with no discipleship, which entirely marginalized the Holy Spirit, and which blatantly ignored the suffering of God’s people here in America.

///

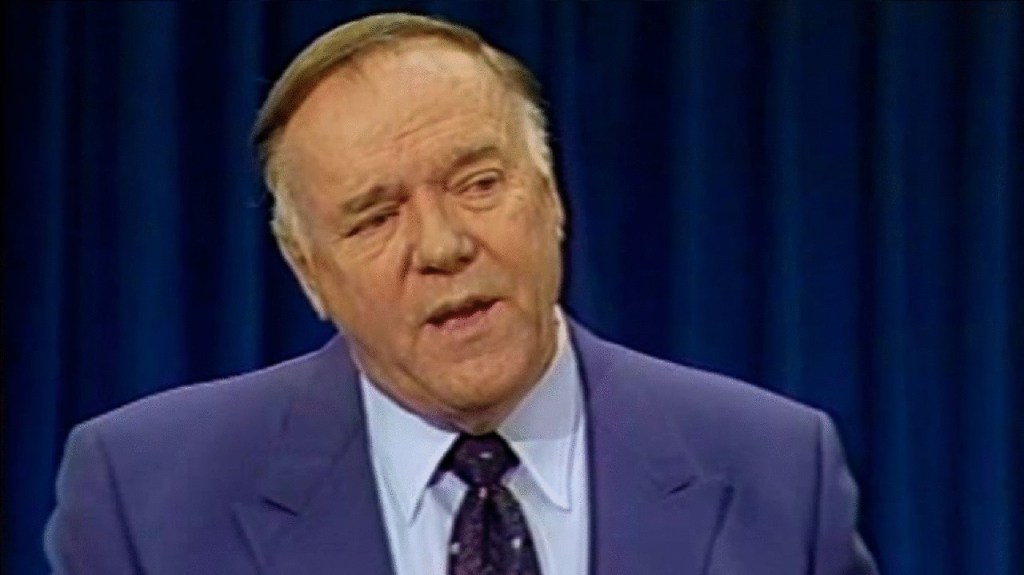

Jimmy watched as Oral Roberts turned every cliche about dirt-poor, hick Pentecostals on its ear. He was a phenomenon, attracting dazzling numbers of followers and great financial success. He was proving that a man could make a very good business out of all this. You didn’t have to be poor to be Pentecostal any more. In 1951 he bought a huge tent that seated 7,500, launching the “tent wars,” each evangelist claiming to have the biggest…

Soon the top evangelists’ tents were bigger than the Ringling Brothers’ Big Top. Faith and miracles were quantified like tent sizes: Roberts boasted that he prayed for 50,000 sick, saved 7,000, or had 13,500 altar calls. He allegedly preached to a million and a half people during 1952, the year Jimmy married, and held 11 tent campaigns; of these he recorded 66,000 who came into the healing line and “38,457 conversions.”

[Pentecostal Evangelist] A.A. Allen calculated that on one tour, “the souls were saved… cost only twenty-five cents each or FOUR FOR A DOLLAR!” He compared this to another evangelist whose cost was $2 per saved soul.

One year, Roberts organized Christian businessmen to underwrite his goal of winning a million souls within the next three years. Then God told him to get out there and save a million more a year for ten years. (Seaman 120).

///

What Roberts was doing would have left a deep and permanent impression on Jimmy. Here he was, a newly married Pentecostal minister with a child in tow. The pressure and anxieties he felt as a high school dropout, working odd jobs and now a small circuit of churches who knew him because of his connection to Jerry Lee instead of his own music, the call to ministry he had received as a boy, the prophecies he gave about World War II began to bring about the same bitternes he had wanted to avoid for so long. At times, he felt paralyzed with fear that he might have misunderstood his calling. Maybe there never was one. If he told people he was a Pentecostal, they would ridicule him like they had when he was a boy. Maybe they would ridicule Donnie too. Every decision had been made to avoid the life his parents had. Yet, decision by decision, here he was entrapped by the thing he feared the most. He was a parent himself, in the very same position. Too harsh with Donnie. Resentful of Frances. Playing music in churches, but unable to play a piano. His father shamed him for how he played, the worldliness of his sound, a bit too eager to impress instead of give glory to the Lord. Even here, where he was most talented, his father and pastors of the churches Jimmy and Frances visited pointed out that he sounded too much like Jerry Lee and not enough like the Spirit of God Jimmy claimed lived in his soul. With all of this talent, he squandered it by playing the accordion like a goddamned circus monkey, smiling big like a idiot clown. What would come next? What new humiliation might God “bless” him with? A fucking small pastorate in the fucking backwoods of fucking nowhere?

///

A life in the Pentecostal mindset had taught him that for every triumph the world might bestow, there was an anti-triumph right around the corner, a big bill with unholy interest sitting on it… He’d been in plenty of humble little preacher’s homes: photos of the grandkids in dimestore frames on the worn-out upright someone gave the preacher and never let him forget it. Sallow lace antimacassars covering the shiny hand-grease stains on the arms of the two “good” living room chairs. The formica kitchen table with chrome legs in the scrubbed kitchen, the hand-me-down silver that tasted like metal, and the breadbox with primitive daisies painted on it by the “artistic” church pillar who sold crafts out of her home – that wasn’t the life Jimmy had in mind. But what if God had it in mind for him?

He was restless and full of ambition. He had talent and he knew it, knew he was smarter than those broken-down old potato-faced hick preachers who, sweet as they were, couldn’t do anything but drone on in the pulpit about how, here’s what you have to do, you should do good deeds, it’s not enough to just go to church, and by the way, you ole sinner, aren’t you ashamed of being such a sorry so-and-so? But God loves ya anyway blah blah blah and the deadly dull prayer meetings where surly, slack-jawed teens were dragged in by worried moms who were in effect begging God the Father to take over raising their louts (Seaman 122).

///

The positive message that Roberts and Peale put forward was a lifeline. Jimmy didn’t have a circus tent like Oral Roberts. He couldn’t claim to be able to heal people by touching them. Jimmy didn’t have a church, especially one attended by the wealthy socialites in New York. He had nothing. And as hard as it was to shift his mindset, he willed himself to believe that was enough. When Jimmy had begun his ministry, it was preaching on the streets of Ferriday. He played the accordion. He invited people he had grown up with, people who knew him and the sins he had committed, to give their lives to God like he had. Many laughed at him, pointing out how threadbare his clothes were. How he hadn’t even finished high school. Wasn’t this the boy who had chopped their cotton? Hauled gravel and tried his best to fix the potholes in their road? Nothing could be more humiliating than that.

///

Word trickled into the backwoods of Louisiana that God had raised up some great healing evangelists who were holding large meetings around the nation. Names like Jack Coe, William Branham, andOral Roberts were often on people’s lips. Gordon Lindsay’s Voice of Healing magazine caried reports of what was happening “out there.” It whetted my desire to see for myself what God was doing in the world. Nannie and I practically devoured every issue of the magazine we received. My heart burned as I read of the thousands being saved, healed, and filled with the Holy Spirit throughout the world.

Just as Timothy’s grandmother Lois built faith into him as a young preacher (II Timothy 1:5), Nannie did the same thing with me. “One day you’re going to preach to thousands,” Nannie said constantly, “just like in these meetings!” Then she would hold up a copy of the Voice of Healing. But it was too much to believe. I felt so inferior and preaching to those kind of crowds looked impossible. Nannie never doubted, but inside my heart I said, “There’s no way that will ever happen.” (To Cross a River 78).

///

Jimmy was reluctant, but what if Peale and Roberts were on to something? What if he ran toward God and took a chance? What if he began to think positively and simply have faith? He wanted to believe and he kept at it, even if it was unclear what would come next. That was something. At least he and Frances had made it out of Ferriday and Wisner; he wasn’t alone anymore. Frances had seen how miserable he had been and she still took a chance on him anyway. That was something. She believed in him. That was something. She stayed with him. That was something. And before any of this, when he was still quibbling over whether to give his life back to God, she went to the altar to get saved right there along with him, even though she was already saved. For better or worse, Frances was committed to Jimmy. She by his side from the very start for whatever might come their way.

///

She was not dismayed. Her great gift that would set her apart from other women was her ability to manage with what she had instead of trying to change it… She wasn’t going to openly take Jimmy away from his mother and grandmother and moild him into her idea of what he should be. Like most girls, she probably did want to do that but she was smarter than most girls. Her style would be to extract the best from Jimmy by mastering the rules he had to live by. She would mold him alright by transforming those rules…

“Three of the most important influences in my life have been women,” said Jimmy at the height of his fame. “They are my grandmother, my mother, and my wife.”

Though Frances was the epitome of femininity, dignity, and grace on the outside, a weak father and a strong mother had made her tough. She didn’t like bloodless, inept men. And she had faith in Jimmy’s talents.

Frances was as close as any woman could come to a copy of Ada [Jimmy’s grandmother, “Nannie”]. As his grandmother’s eyes blazed when Jimmy prayers timidly and she would thunder, “You’re not praying to a PUNY GOD!” so Frances’ philosophy was, “Whenever you have problems, you learn to overcome them, to solve them, to knock the door down.”

The moment he married her, Jimmy surrendered himself to the fate thrust on him… That Frances was a catalyst for this fate became clear shortly after the marriage, when she had a little chat with Jimmy’s mother. Minnie Bell invited her into the kitchen one night and sat her down. “The Lord called Jimmy into ministry when he was eight years old,” Minnie Bell told the 15-year-old girl. She told Frances he would “never be able to escape that call.” He was going to preach the Gospel, she said.

“I was sitting shaking in that chair,” Frances said. “I didn’t know what was happening to me. It was like something was unveiled in front of my eyes.”

She attributed it to the hand of God, but it was likely that she also had a realization of what Ada, Sun and Minnie Bell, Mickey [Gilley] and David [Beatty] and Jerry [Lee Lewis] and the other cousins, sweet John Lewis and Aunt Reenie and Sister Wiggins, Brothers Janway and Roccforte and all the preachers and family members and church faithful had invested in: the promise of Jimmy Swaggart, child prophet, tow-headed prodigy, anointed of the Holy Ghost, Chosen of God. Years later, Frances added that she had heard a clear voice in her own head telling her that it was going to be difficult to honor Jimmy’s call, but she had been tapped and if she didn’t do right by the commission, “I’ll remove you and replace you with someone else.” Frances didn’t say whether it was a man’s voice or a woman’s. But if Minnie Bell had been blunt enough to say exactly what she wanted to, those would have been her words. In that moment, Frances understood that she had married into someone else’s project, and that she’d better get out of the way or get on board (Seaman 125, 136).

///

With all this running away from God, Frances suggested Jimmy do things he had been running from for years. He needed to play to his strengths instead of holding on to his weaknesses. He needed to play the piano. He needed to embrace his anger and use it for holy purpose in his sermons. He needed to record an album. He needed to embrace who he was, who he always had been – a wild man, a fire-breather, one of the best piano players in America. He needed to stop living in his father’s shadow, in Jerry Lee’s shadow, and make his own way in the world. Let Roberts have his healing lines, Peale his self-help books. Jimmy did not need to emulate them. He was meant for something else.

One night, he felt the full weight of the expectations placed upon him. After several days of debilitating depression and fear, he started to come to terms with some things until he could hardly bear it anymore.

///

I had set standards for myself so high that I couldn’t live by them. As a result, I fell deeply into condemnation. Gradually, I came to think God had a grudge against me because of my constant failings. I didn’t realize He sees us not as we are, but as we shall be. The voice of the enemy drove me further into discouragement and depression. “God won’t forgive you again,” voices said, “You’ve told Him you wouldn’t sin again and yet you have.” Slowly, I was coming to think there was no hope.

///

He went to a doctor to try and get an explanation for the anxiety and depression that consumed him by day and interrupted his sleep at night. The doctor told Jimmy it was a nervous condition and if he did not find a way to relax, get some rest, he would have a nervous breakdown. Frustration and despair started to coalesce around him. Exhausted, he began to hallucinate.

///

I went outside out trailer and tried to walk down a darkened road in hopes I could exhaust myself enough to sleep. It was just before dawn when I came back, the darkest time of the night. It was a haunting time, a strange time to be awake and fearful. Iwwent to bed when I climbed back into our tiny trailer. And for the next few moments I did not know if I was wide awake or dreaming, but suddenly I found myself in an old house with high ceilings. The room I was in had no windows or furniture. A door leading outside was slightly ajar. Fear welled up inside of me. I knew I was in an evil place…

Suddenly, the door swung open and a hideous-looking beast stood towering over me. He had the body of a bear and the face of a man. The expression on his face was the girsliest I had ever seen. The beast was the picture of evil… I looked around for some weapon to use even though I knew the room was bare. He was almost an arm’s length from me now. “In the name of Jesus,” words spoke from inside me… This time I shouted it, “In the name of Jesus!”

Instantaneously, he was swept out the door as I came to myself. When I did, my hands were lifted toward heaven and I was speaking in tongues. I was miraculously freed! It was the beginning of being taught the power in the name of Jesus… the difference between life and death (To Cross a River 79-81).

///

Jimmy had come to embrace a different kind of confession, one that did not place emphasis on the self, positive thinking, the ability of a celebrity minister, or reciting scriptures out of context. Apart from Oral Roberts, E.W. Kenyon, Norman Vincent Peale, and a collection of other ministers across the spectrum, Swaggart had reclaimed a teaching of early Pentecostals who believed power resided not with one self, as though humans had some inherent goodness, but with the Almight Savior who was the embodiment of everything good.

Pentecostalism had, since the start of the Twentieth Century, placed tremendous emphasis on the power of speech – tongues, in particular, but speaking out declarations made in the Bible. Exorcisms were performed by speaking the name of Jesus, by reading scripture out loud, by creating a welcoming environment for the presence of God through God’s word. It wasn’t the incantation of magical phrases like “the name of Jesus” but instead an assuredness of speaking with the voice of God. In the Christian Scriptures, the Book of Jude recounts an apocryphal legend about the body of Moses after the prophet had died. “Even the archangel Michael, when he was disputing with the devil about the body of Moses, did not himself dare to condemn [Satan] for slander but merely said, “The Lord rebuke you!” (Jude 1:9). The Apostle Paul, when a child possessed with an evil spirit began to praise him, commanded the spirit to release the girl. There was, to the Pentecostal believer at least, something to all of this. Praising a minister, even when saying true things, did not necessarily mean God’s spirit was present. In the supernatural realm, angels argued with one another and concluded the matter with a mere dismissal. “The Lord rebukes you,” as if to say, “What more needs to be said here? You’ve already lost the debate.”

With all of these legends and prophecies swirling around Jimmy, the only person who didn’t seem to believe them was, well, Jimmy. Even demons and half-bear-half-man spirits sent to torment him and disrupt his sleep seemed to believe Jimmy was worth attacking.

He got up once more, infused with new confidence. He channelled his fears.

///

I value your souls, and knowing the terror of God, I persuade men. One day, I will have to stand before the God of all the ages and He will call my name and men like Paul and Peter will step up and my Heavenly Father I couldn’t hold their sandals of their feet, and I will have to answer for those television cameras and the millions upon millions and millions upon millions and God forbid that one soul clutch at my coat tail and say, ‘You didn’t tell me, you didn’t tell me!’

This is the most dangerous hour the Church has ever known. This is the most dangerous Pentecostal Church has ever known. This is the most dangerous hour!

I sat with the greatest leaders in Pentecost the other day… we sat there, you know them, and we wept and pleaded. ‘What are we gonna do?’ (from sermon on 17 May, 1986. delivered in Kansas City, Missouri. “The Message of the Cross”).

///

When he had applied for ordination with the Assemblies of God the first time, the committee saw Jimmy Swaggart for what he was, a smiling monkey with an accordion. On a leash.

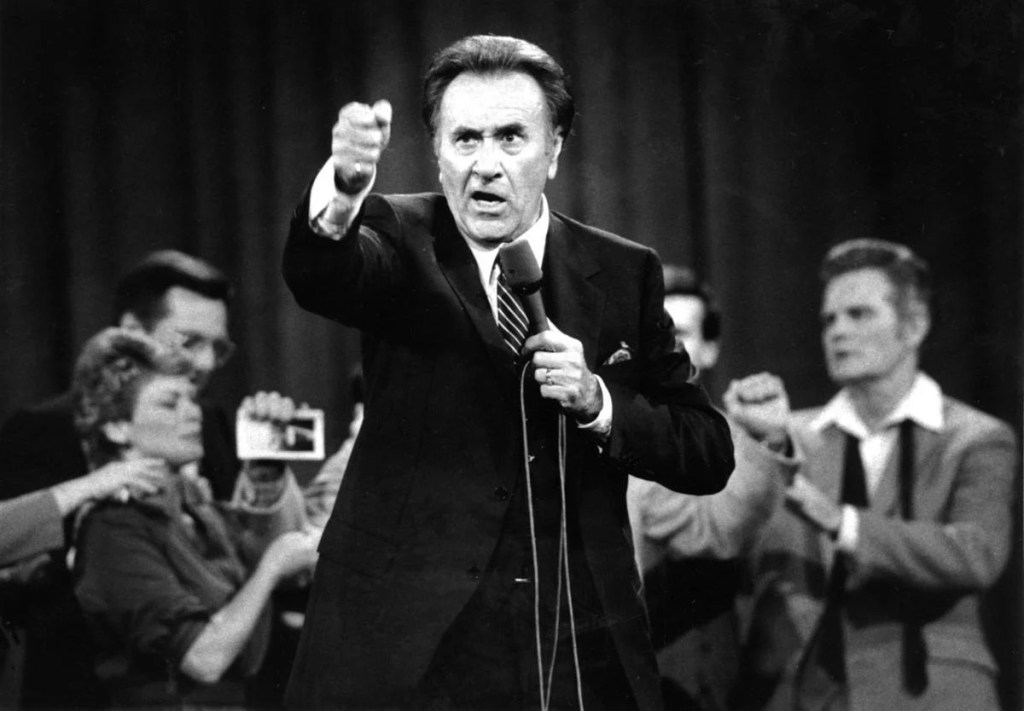

Put him behind a piano though, he was a direct alternative to Jerry Lee Lewis.

Put him behind a pulpit, and he was a wild man, screaming and shouting to whip his audience into a fury.

Unlike Jerry Lee, Jimmy kept pressing. He drove his audiences over the edge, hands firmly on the wheel. He never blinked again, now confident in his calling. He didn’t kick over benches or stand atop pianos like his cousin, for the spectacle of it. He was far more disciplined, far far more in control of how to work a room. He had purpose. He had a direction. Lonely though he may have been, his best friends were God Almighty, the Lord Jesus Christ, and the all-consuming Holy Spirit whose fire burned hot and changed lives. Jimmy Swaggart was living proof that God could not be strapped down under dusty tents in the middle of Oklahoma. He was proof that people didn’t need to believe in themselves; they needed someone to believe in them.

In the coming years, the lines of belief would begin to blur. Jimmy believed in Jesus and Jesus believed in Jimmy. Frances believed in Jimmy.

Jimmy applied for ordination with the Assemblies of God and, this time, they believed in him too.

Frances still believed in Jimmy. She believed he needed to cut another record. And then another. They sold records out of the trunk of their car and the more they sold, the lighter the load became both literally and figuratively. Selling records became a solid, steady source of income for them. Now, Frances said, they needed to find a larger audience. One beyond the South.

One thought on “Biography: Jimmy Swaggart, Chapter 8”