Predictably, Jimmy’s religiosity falls off around this point. He receives salvation, he is filled with the Spirit of God, he voraciously reads the Bible, he speaks in tongues, he feels called to ministry, and his prophecies of destruction have come true. Every indicator is present that there is something remarkable and unique about him until he experiences the flood of teenage rebellion and finds companionship with the sinful trajectory of his cousin, Jerry Lee Lewis.

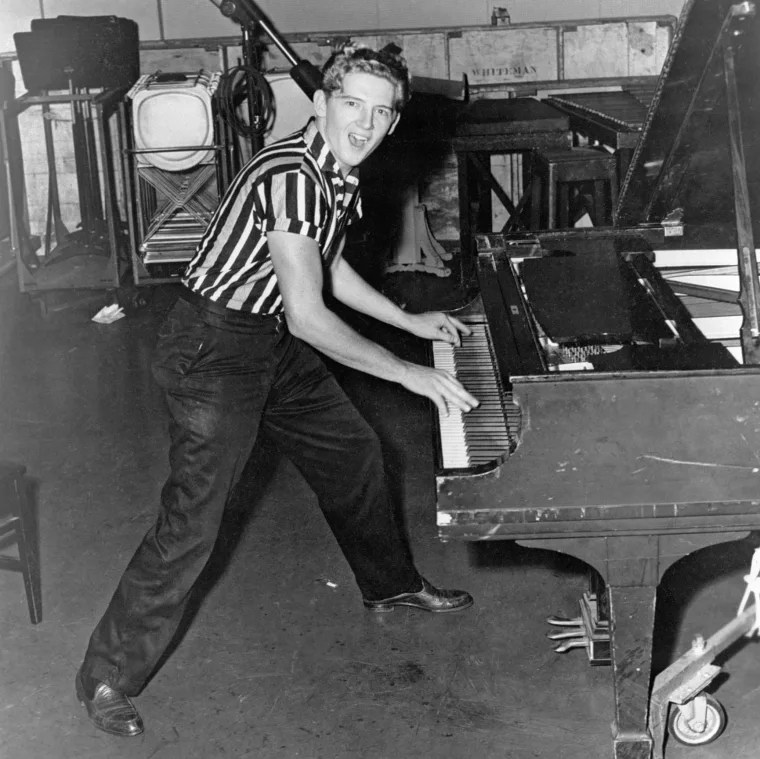

While Jimmy was reading the Bible, speaking in tongues, and memorizing the stories of early Pentecostalism his grandmother taught him, other members of the family were less inclined. Cousin Jerry Lee Lewis, it appeared, was unable to grasp the basics of elementary education. This would continue to present challenges for him throughout his life, contributing to a sense of inferiority even in the midst of global fame and fortune. As children, Jerry Lee’s shortcomings required the more studious Jimmy to step forward and speak on his behalf with teachers on more than one occasion. Remarkably absent from both men’s versions are their parents. Jerry Lee was quite intelligent, only in ways not accepted by the Louisiana Board of Education. He had taught himself to play the piano and studied the sounds of jazz, rhythm & blues, and bluegrass until he became a walking compendium of stories collected from the lives of those who grew up in Ferriday, Whites as well as Blacks.

In hindsight, Jerry Lee was also prophetic, albeit a different kind of prophet than the ones Jimmy revered. Jerry Lee’s prophetic utterances were countercultural, ridiculing the hypocrisy of the overzealous who made a big to-do over following God when they didn’t have a lick of sense to even know what that meant. He was prophetic in naming his own racist upbringing, insisting that racism was a sin of which the people of Ferriday needed to repent. Like Jimmy, he became consumed with a lifelong fear of God’s judgment except that he never felt himself above such judgment, as Jimmy often did. Jerry Lee knew his faults well and, lest he ever forget them, everyone around him seemed eager to point them out – in school, at home, practically everywhere he went. He remained terrified that, with his limited abilities in something as tawdry as music, he would face eternal damnation. It was beginning to make him feel like he was crazy.

Jerry Lee often left school or found a way to sneak out at night. Despite their differences, Jimmy was more like a brother to him. Jimmy felt the same way. In some ways, Jimmy envied his cousin. While Jimmy predicted destruction at a distance, Jerry Lee would run towards it, any kind he could – physical, relational, spiritual, melodic. In time, Jimmy would see Jerry Lee’s “magnetism” and ability to hold others in thrall as demonic, but as teenagers they were inseparable. As Jerry Lee’s activities escalated, becoming more dangerous and more frequent, from cheating a local store on empty glass bottles to breaking and entering homes, Jimmy naturally fell in with his cousin’s thievery. There was, however, a line Jimmy would not cross. While Jimmy predicted destruction at a distance, Jerry Lee would run towards it, any kind he could – physical, relational, spiritual, melodic. Something more than school attendance began to distinguish the cousins from one another.

Jerry Lee was not seeking mindless damage for its own sake. His rebellion appears at times to be an expression of restless energy, a search for meaning and, not able to find any, a turn toward self-destruction. Lewis was influenced by a piano-playing older cousin, Carl McVoy. McVoy would go on to record with Bill Black’s Combo. Perhaps this is where the seed was sewn, but Lewis by all accounts had a preternatural ability for music, particularly the piano. Like Swaggart, he grew up in poverty and had to have seen the frustration and disappointment of Ferriday and Northeast Louisiana as a greater prison than the penitentiary. Desperate to help and willing to do anything for their son, his parents mortgaged their farm to buy him a piano. It was the only thing he was ever good at and, at least to Swaggart’s recollection, so immediate was Jerry Lee’s ability to play the piano that it seemed like the boy was inspired by the devil himself. McVoy never reached the pinnacles of fame to which Jerry Lee would ascend, but at least it gave the boy someone to look up to. In McVoy and even Sun and Minnie Bell Swaggart, Jimmy’s parents, Jerry Lee would have seen a slim chance at a life where he wouldn’t have to work a field like his parents. He took inspiration from the radio and the sounds from Haney’s Big House, a black juke joint across the tracks, replicating and perfecting the sounds that he heard with clarity and even, as he continued to find the limits of his own ability, perfected.

On November 19, 1949, when he was only fourteen years old, Lewis made his debut with the first public performance of his career playing with a country and western band at a car dealership in Ferriday. The hit of his set was his performance of R&B artist Stick McGhee’s “Drinkin’ Wine, Spo-Dee-O-Dee”. On the live album By Request, More of the Greatest Live Show on Earth, Lewis is heard naming Moon Mullican as an artist who inspired him. Mullican was not the only artist to whom he would be indebted. Though his teachers may have thought the boy dim-witted and a wastrel, his disregard for farming evidence that he was lazy and disrespectful, unable to see his own future, Lewis was cataloging sounds and other artists with an encyclopedic mind that other artists aspire to. He was, to be clear, not only gifted but a musical genius.

He was also becoming an alcoholic. Prone to violence, too old for the strap, and unable to suppress his “demonic” attitude, his mother did the only thing she knew to do. Mary “Mamie” Herron Lewis enrolled him at the Southwest Bible Institute in Waxahachie, Texas. Though he may have laughed in derision at the holy rollers in his family, Jerry Lee’s love and devotion toward his mother was without question. She was the only person he was afraid of, the only woman he ever loved and obeyed. Trying to straighten her son out, Mamie wanted to send her son away and live in peace, to entrust her son to God who, she hoped, might redirect his gifts and talents toward singing evangelical songs exclusively. Maybe then, he might fit in with the rest of the family and have the self-control necessary to keep him out of jail.

It was a short-lived experiment.

When Lewis daringly played a boogie-woogie rendition of “My God Is Real” at a church assembly in Waxachachie, it ended his association with the school the same night. Pearry Green, then president of the student body, related how during a talent show Lewis played some “worldly” music. The next morning, the dean of the school called Lewis and Green into his office to expel them. The experience probably turned Jerry Lee away from the path of God forever. Instead of humiliating or shaming, it hardened him. It was yet another rejection by holy rollers, a refusal to recognize who he was and what he was made to do. The only language he knew to explain his talent as demonic, his abilities unearned but given as a gift from Satan. The people who claimed to love him continued to turn him away, send him off, and insist that he give up the only thing he was good at. He probably felt that everything he did, every note he played, would bring about another death. Tellingly, he began to refer to himself as “The Killer.”

Lewis went home and started playing at clubs again around Ferriday and Natchez, Mississippi, this time without apology. He threw himself into the work, channeling his anger and rejection into creating the thrill of working a crowd. He became part of the burgeoning new rock and roll sound and cut his first demo in 1952 recording for Cosimo Matassa in New Orleans. Three years later in 1955, he traveled to Nashville, where he played in clubs and attempted to build interest, but was turned down by the Grand Ole Opry, which “made” new artists, because he was already playing the Louisiana Hayride country stage and radio show in Shreveport. Even the Grand Ole Opry had to acknowledge that Lewis was already famous and Nashville had nothing to teach him. Lewis didn’t receive it as an insult.

In November 1956, Lewis traveled to Memphis, Tennessee, to audition for Sun Records. Label owner Sam Phillips was in Florida, unbeknownst to Lewis, but he convinced producer and engineer Jack Clement to roll the tape and record him anyway. Lewis performed a rendition of Ray Price’s “Crazy Arms” and his own “End of the Road.” In December 1956, Lewis began recording prolifically as a solo artist, building a catalog, while maintaining steady work as a session musician for other Sun artists, including Carl Perkins and Johnny Cash. His distinctive piano playing can be heard on many tracks recorded at Sun in late 1956 and early 1957, including Carl Perkins’s “Matchbox”, “Your True Love”, and “Put Your Cat Clothes On” and Billy Lee Riley’s “Flyin’ Saucers Rock’n’Roll”. His family may have thought he was lazy, but his dedication to working hard and developing his sound by working with others is a testament to his drive and commitment to something he loved. Despite the public persona he crafted on stage of selfishness and breaking convention, he genuinely cared about making sure the artists he worked with had a signature sound. Further complicating the image he was cultivating on stage, on December 4, 1956, Elvis Presley dropped in on Phillips to pay a social visit. Johnny Cash was also there, watching and giving feedback while Perkins was in the studio cutting new tracks with Lewis backing him on piano. The four – Cash, Lewis, Perkins, and Presley – began an impromptu jam session and Phillips left the tape running. These recordings were released on CD as “The Million Dollar Quartet” and included tracks of the four working with Presley’s “Don’t Be Cruel” and “Paralyzed”, Chuck Berry’s “Brown Eyed Handsome Man”, and Pat Boone’s “Don’t Forbid Me”. Almost half of the remaining tracks were gospel songs.

According to several first-hand sources, including Johnny Cash, Lewis was troubled by the sinful nature of his material, even more than the brief depiction of him as a rambling drunk in the 2005 film Walk the Line, based on Cash’s autobiographies. Lewis was, as Cash described him, a devout Christian who loved people. Even on the road, he would engage the other musicians and even strangers in conversation about their spiritual life, asking whether they were saved, what church they went to, whether they spoke in tongues. At times, his questions seemed to be seeking the assurance he freely gave others. How did people know they were saved? Did they believe God loved them? No, really, how did they know for sure? Lewis, in complete contradiction to the character he became on stage, was terrified that he was leading his audience to Hell. He was sure that, despite his soft heart, nothing mattered. He was inescapably going to Hell. Maybe he was destined for it.

As a solo artist, “Crazy Arms” went on to sell 300,000 copies in the Southern United States. Lewis’ background work and the instant respect he had with everyone he worked with was enough to get an invite to go on tour with the likes of Elvis Presley and Johnny Cash, good ol’ boys from nowhere like him. Jerry Lee kept putting out hit after hit. His 1957 hit “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On” rocketed him to worldwide fame. 1957 would secure his status as a rock n’ roll legend, especially after he married his 13-year-old first cousin, Myra Gale Brown. Not to be outdone, Elvis would marry 14-year-old fan Priscilla Presley a decade later. Lewis, at least in retrospect, cultivated the image of a wild scofflaw rocker and while many of his fans were shocked at his questionable marriage to a child, Lewis sneered. He was used to criticism and people being disappointed at him, shaking their heads and clucking their tongues. The judgment of his critics, he pointed out, was evidence of their hypocrisy. As he had done several times before, he used the criticism as fuel for creativity. He followed up “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On” with a string of hits like “Great Balls of Fire” and “Breathless” to “High School Confidential”. Before Elvis, Jerry Lee was the King of Rock n’ Roll. Before Johnny Cash, Lewis was the King of Country, the pioneering King of Rockabilly, the Devil Prince of Wild Behavior, commanding every stage he ever played on. By the end of his life in 2022, Lewis had a dozen gold records on the wall, four Grammys on his mantle, including a Lifetime Achievement Award and two Hall of Fame Awards in Rock and Country. In 1971, as rock began to take a turn into a new sound, music critic Robert Christgau said of Lewis: “His drive, his timing, his offhand vocal power, his unmistakable boogie-plus piano, and his absolute confidence in the face of the void make Jerry Lee the quintessential rock and roller.” In 1986, Lewis was inducted into the inaugural class of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. In 2022, he joined the Country Music Hall of Fame. In 2003, Rolling Stone listed his box set All Killer, No Filler: The Anthology on their list of “500 Greatest Albums of All Time.” In 2004, they ranked him in the top quarter of the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time. It was the validation he had always been denied with a level of fame and fortune his family had never even been able to imagine.

Lewis’ temper was famous, especially when he was drinking. He was violent. Or so it seemed. As part of his stage act, Lewis would get caught up in the music. His inaugural television appearance on The Steve Allen Show, in July of 1957, demonstrated some of these moves when he played “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin On”. He would kick the piano bench aside, out of his way, to play standing instead. Audiences knew immediately that the bench was not the only thing that had been kicked aside. Decorum was gone, the mindful softness of previous generations. Lewis would rake his hands up and down the keys, his fingers moving with such speed that cameras could only see a blur as he reordered cacophonous notes into shape. When he was done, or simply bored of one song and ready to move on, he would often conclude by banging the keys with his heel, sitting on the piano, laying on the floor and playing blindly upside-down, by jumping on top of the piano or screaming with the crowd in their frenzy. The roar of the audience was part of the act – their cheering, raucous interruption, wide-eyed mania, the hysteria of it all. It was either a perverted counterpoise to the spiritual expressions he had grown up with or their fullest expression running over to excess. But when he was offstage, Lewis was thoughtful and quiet, sometimes taking the role of a teacher. He told the Pop Chronicles in 1969 that kicking over the bench originally happened by accident, but when it got a favorable response, he kept it as part of the act. He wanted to inspire other musicians, coming up. To be the patient, loving father they never had. He would begin to answer a question, purse his lips, and begin walking through the history of music to explain that, no, not at all. He was not as wild as he seemed. He played while standing because it allowed more force to the note, not because he was showing disrespect to tradition or classical music – God forbid! He was building on the work of others, never trying to cast their work aside. Beneath the character of hard living and music, he needed the crowd’s approval, their love for the character he was developing. His stage presence was only “wild” because he was pushing the limits of music. Whenever he bent the rules, it was because he knew them and knew how pliant they really were. He would never try to break music. He loved it far, far too much to do it harm. He may have been Rock & Roll’s “first great wild man”, it’s first great eclectic”, but pianists who came after him acknowledge Lewis brought the instrument forward. Classical composer Michael Nyman cited Lewis’s style as the progenitor of his own aesthetic, Elton John studied Lewis thoroughly to understand how he was still able to collect notes as he “raked” the keys. Cameras saw Lewis’ hands move in a hazy blur, a smear of activity on celluloid. What they weren’t able to catch for many years was that Lewis’ fingers were moving even faster. He was impatient for the rest of the world to catch up.

At home, Jerry Lee would buy cars but barely drive them. He was suddenly more wealthy than he could understand, and the only thing he knew to do was buy cars and park them in the yard just for the status, to show everyone that he owned a fleet of Cadillacs. To show everyone he wasn’t a screw-up. He wasn’t stupid. He was richer than them, smarter than them, he had made it. But it was a level of excess that, whenever he went home at least, was still denigrated. Jimmy, whose early ministry profited from his cousin’s fame, would tell tens of thousands in his television and stadium audiences that Jerry Lee’s success was attributable to the devil. That was the only explanation. It didn’t amount to anything. It was flashy, sure. And no question, Jerry Lee was rich. Sin was loud, like Jerry Lee. It was prone to excess, like Jerry Lee. It was a corrupting influence, further entrapping a person’s soul. Jerry Lee had, Jimmy said, agreed with the devil early on, trading his soul for music. His wealth was proof that a soul was valuable, that the devil was willing to pay any price for the soul of someone who grew up in a true-blue, Bible-believing family like theirs. The insult was that Jerry Lee knew better and still chose the darkness. Nothing else could explain his uncanny ability to play the piano, to hear melodies and improve on them, to whip audiences into a frenzy. Jerry was evil. He was spellbound, in thrall with the forces of darkness, damned forever. Jimmy wasn’t the only one in the family who saw it that way. Lewis doubled down on his wickedness in frustration, his rebellion and erratic behavior turning toward the outright destructive. His personal life, which at first was left out of the papers because he was merely a talented background player, would become fodder for his stage performance. Lewis blurred the lines as much as possible, playing with the talented artists who came through the doors of Sun Records to insulate and protect himself through powerful associations. Later, as a solo artist, he would play with “demonic” intensity to bang and pound against the inevitable.

Lewis was married seven times; the first two took place before his career really took off. When he was 16, he married Dorothy Barton, the daughter of a preacher; the union lasted from February 1952 to October 1953 and is only remarkable because it made his second marriage bigamous and illegal. Lewis’s second marriage to Sally Jane Mitcham in September 1953 occurred 23 days before his divorce from Barton was finalized. They had two children: Jerry Lee Lewis Jr. (1954–1973) and Ronnie Guy Lewis (b. 1956) until he filed for divorce four years later in October 1957. His third marriage was to 13-year-old Myra Gale Brown, his first cousin once removed, on December 12, 1957. As before, this marriage was technically illegal and bigamous since his divorce from Jane Mitcham was not finalized before the ceremony took place. He would remarry Brown on June 4, 1958, but continued celebrating the earlier date. Critics rightly pointed out the dubious nature of the marriage. Not only was it illegal because of bigamy laws but also because Myra was underage as well as his cousin. The marriage almost ended his career. Though he was an exceptional piano player, most of America could not look past a child bride, her petite body swollen with a baby while she was still a child herself. They had two children: Steve Allen Lewis (1959–1962) and Phoebe Allen Lewis (b. 1963).

In 1970, Brown filed for divorce on the grounds of adultery and abuse, stating that she had been “subject to every type of physical and mental abuse imaginable.” The press, on Lewis’ heels since the marriage, now helped Myra share details of her abusive relationship, how Lewis normalized marital rape and drug usage, his drunken behavior, relentless cruelty. His audiences may have been able to set aside the private life of their favorite artist, but it was becoming clear that while Jerry Lee Lewis was talented, he was unable to escape the small-minded cultural poverty of his youth. As a generation matured and sobered up, Lewis was increasingly failing to adapt to the times. Whatever popularity had weathered the storm of his marriage to Myra eroded following the scandal of their divorce.

Lewis’ career saw fewer and fewer hits. His cover of Ray Charles’s “What’d I Say”, for example, did well on the charts, but Lewis did not have much chart success in the 1960s, and his performances, increasingly wild and energetic, saw declining ticket sales. His 1964 live album Live at the Star Club, Hamburg was another exception. It is regarded by many music journalists and fans as one of the wildest and greatest live rock albums ever. The death of Steve Allen Lewis exposed how fragile and prone to depression Lewis was whenever he was offstage. But it was not the only, or even the most significant derailment. What should have been a step forward for Lewis’ career in 1963, leaving Nashville’s Sun Records for international stardom with Smash, a subsidiary of Mercury Records, almost ended his career entirely. Mercury was itself a subsidiary of Universal Music Group and had power approaching a monopoly over radio stations, promotions, publications, arenas and concert halls. It was the perfect fit for Lewis, a logical next step, except for one critical shift in music – The Beatles. As Colin Escott writes in the liner notes to the retrospective A Half Century of Hits, “Mercury held the presses,” throwing their weight behind Jerry Lee, “and it might have happened if the Beatles hadn’t arrived in America, changing radio playlists almost overnight. Mercury didn’t really know what to do with Lewis after that.” Abrupt ends to fame and pivots that came almost too late, both would become familiar experiences to the family.

In 1968, Lewis made a transition into country music and had hits with songs such as “Another Place, Another Time”. The transition helped reignite his career. His personal struggles with alcohol and drugs exposed by the divorce from Myra and the death of their son, also helped audiences reconnect and see him sympathetically. Throughout the 1970s, he regularly topped the country-western charts; 30 songs reached the Top 10 on the Billboard Country and Western Chart like his “To Make Love Sweeter for You”, “There Must Be More to Love Than This”, “Would You Take Another Chance on Me”, and “Me and Bobby McGee”.

As Jerry Lee forged new connections, he brought along Mickey Gilley, Jimmy and Jerry Lee’s “other brother” cousin. Gilley and Lewis both hoped to build on the legend of musical talent in Ferriday. Years before, Jimmy had declined a record deal with Sun Records. Mickey wasn’t going to make the same mistake. Using Jerry Lee’s connections and possessing an intuition about where the music industry was headed, Gilley began his career singing country and western, like Jerry Lee, but moved towards a more pop-friendly sound in the 1980s that Lewis never embraced. The pivot would bring Gilley success on not just the country charts, but the pop charts as well, amassing 42 singles in the Top 40 on the U.S. Country charts with hits like “Room Full of Roses”, “Don’t the Girls All Get Prettier at Closing Time”, and a soulful remake of “Stand by Me”. Ultimately though, Mickey would have to acknowledge he was merely playing in the shadow of Jerry Lee. He wasn’t as crass or as viciously driven. He wasn’t willing to sell his soul to the devil.

Gilley had consistent success of his own in country music and recording covers of love songs, found stability in opening clubs and bars. He backed away from the temptation to emulate Jerry Lee, seemed afraid that he might imperil his soul just like his cousin if he wasn’t careful. He wasn’t as talented as Jerry Lee, he knew. Surely, the devil would buy Mickey’s soul for a much lower bargain. As Jimmy would say, it was best to flee evil while he still could. Building the honkytonk, Mickey’s Pasadena, was as far as he was willing to imperil himself. It was his way of psychologically distancing himself from evil while still profiting from it. If the world was going to end, like Jimmy said, at least people could dance and tip back a few drinks. In Jimmy’s sermons, Mickey’s accumulated wealth through nightclubs and rodeos was an expression of worldliness more than actual demonic activity. His clubs, even his music, were not explicitly sinful. They were whatever the guests and audience made them out to be. A good person could still go to a bar, could still go to a nightclub, could bring their entire family to a restaurant that served alcohol, and maintain their Christian walk, Swaggart claimed. After all, he did it all the time. Jesus ate and drank with sinners. Jimmy, when the opportunity allowed, did the same thing.

It was a thin line, one that Swaggart would increasingly play with and occasionally cross. There was nothing inherently sinful in building dance halls, after all, even if they were still “dens of iniquity” filled with “filth and fornication and tommyrot.” Jimmy’s tirades were not against inanimate objects but people. Like Gilley, Swaggart began to invest in land, using the money he amassed through strict living and generous savings together with the blossoming success of record sales to build a recording studio, then printing facilities. He began speculating in real estate and development, buying farmland outside of Baton Rouge. Like Gilley, he had plans to do something beyond music and wanted the security of passive, consistent income. He didn’t want to become an old man dependent on donations from churches, like so many other ministers he met on the road. Sin still crouched at the door. The temptations of the world, the flesh, and the Devil still lay before each of them, biding time and waiting for an opportune moment of weakness.

As Jerry Lee ascended to stardom, Jimmy languished. He had been left behind, which to the Evangelical mind is a kind of psychological torment. More than that, his continued poverty and the failures of inexperience in youth were in stark contrast to the rocket-like trajectory of his cousin. His early call to ministry still pressed upon him, even as he denied its existence and tried to rewrite the narrative. Sure, he dabbled in churchgoing. He spoke in tongues. The entire family did. What of it? Maybe he wanted to become a boxer instead, to go further than his father had. Maybe he wanted to play music. The entire family was talented when it came to music. Jerry Lee was proof enough that life existed outside of the little towns of Louisiana with their sweaty churches, rotting plantations, marshy farmland, and dusty summers. Maybe Jimmy could do have a shot at a real life once he left Ferriday but as childhood fell away, resentment and frustration began to take hold. Jimmy was the oldest cousin, the gifted one, but that did not mean anything came easier to him. Jerry Lee’s success was unnatural, a mockery of the call of God on Jimmy’s life, a perversion of the life Jimmy could have had if he had followed Jerry Lee into a life of music. Jimmy was naturally talented at music. The entire family was. He learned how to play the accordion from his mother, developed a baritone like his father, learned to play the piano too, like Jerry Lee. Notably, it did not come as naturally for him as it did for his cousin, the two in constant competition for grades, affection, and attention. As Jerry Lee’s talent – his “gifting” – became more evident, as it attracted attention, eager girls, money, and fame, all of this caused Jimmy to wonder what his own life would like. All Jimmy had was God, and he wasn’t sure that would be enough.

By the time I had reached thirteen, the other boys whom I had grown up with – Jerry Lee, Mickey, Sullivan and David – were no longer interested in church or the things of God. I was basically the only young person my age trying to live for the Lord. We would all get together and talk. But later they would leave and go to the movies. It became a lonely, dreary time. I was constantly plagued with thoughts I was missing out on life (To Cross a River 45).

These feelings more or less culminated around the movie theater, where Jimmy claimed to have been saved and felt the call on his life. The theater was a crucible, in the end. Five years earlier, he had run away from it. Now that everyone at school, his cousins, and everyone outside of the close-knit family socialized by going to the movies, he questioned whether he had been too eager. In hindsight, maybe the whole thing had been imagined to satisfy his parents and grandmother, who kept pressuring him to stop acting like a child, to stop being so lazy, to grow up, to do the right thing, to get saved. The expectations were a boiling pot, too much for him. Something inside began to scream for release.

Finally the pressure got to me and I went to daddy. He and mama were resting on the bed that Saturday afternoon. I hadn’t been to a movie in five years. “Daddy, do you think it would be okay for me to take in a movie this afternoon?” I asked. “All the guys are going.”

He was reading the town’s weekly newspaper, but looked up as I spoke. He was crying. So was mama. Obviously, their commitment to God was much deeper than I had suspected. They had surely noticed that I was not the “spiritual boy” I had once been. My request wounded them (45-46).

For Pentecostals, shunning the world was crucial to maintaining one’s holiness. 1 Thessalonians 5:22 said that believers were to “abstain from every form of evil”, James 4:7 taught that a believer should “submit yourself unto God” and “resist the devil,” promising that evil would flee. One verse later, in James 4:8, the writer admonishes that the believer needed to “purify your hearts, you double-minded.” In the Gospel, epistles, and Revelation of John, it is clear that Christians are to stand apart from “the world” and its various temptations. Christians are to have their own distinct culture and not participate in worldly pursuits, culture, or practices. For some religious groups, these teachings taken together construct a rigid legalism. A believer’s salvation is constantly in jeopardy for relying on the world instead of God. This legalism takes many forms. The Amish, notably, refuse to dress like everyone else – “the world.” They have created a culture of their own, one of mutual reliance inside the Amish community. Hasidic Jews do something similar, even establishing their own educational system to avoid corruption from the lies of outsiders. Baptists say they do not drink or dance, but jokes abound regarding their selective obedience on such matters. For Muslims in the West, the daily call to prayer and food practices are countercultural evidence of their devotion. Pentecostals, in this way, are comparatively tame in rejecting the culture and entertainment most Americans enjoy. Music, like the rock n’ roll of Jerry Lee Lewis and Elvis Presley are notable examples, but before this most Pentecostals made a point of rejecting Hollywood. Not even an industry-wide effort by Hollywood to avoid governmental oversight through self-censorship, the Hays Code which began in the 1930s, or the various passion plays and Biblical adaptations were enough to budge Pentecostals from their outright refusal of what they saw as degeneracy. Movies were not evil in and of themselves, as though the celluloid itself held some dark power. It was the messaging that came through, the perversion of tradition, women painted up like whores and men freely joking as though life were anything other than hardship. Often set in larger cities, movies were a false god, a Babylon promising a better life and – whether implicitly or explicitly – defying God, mocking God’s people who prayed regularly and depended on the land. Pressed, there is a reason Pentecostalism never developed a robust theology. They saw evil lurking everywhere, always threatening the life of the believer. As the century moved forward, belief in the supernatural presence of God necessitated a matching evil. As Pentecostalism became more widespread, so too did the forces of darkness; Pentecostalism saw popularity in locations with already robust folklore and folkways throughout the American South, the cricks and hollers of Appalachia, and then it began to take hold in Africa and South Africa, in Argentina and Brazil. This popularity, dependent on people who already had a belief in evil forces moving among humanity and sometimes possessing individuals, would further expand in the 1970s, taking on apocalyptic tones.

When Jimmy was a young believer, the apocalyptic was already present. Belief in the supernatural, in possessions, and demonic influence, felt very close and intimate to him. His grandmother spoke in tongues regularly and claimed to know Jimmy’s future. He would preach the Gospel and go all over the world. His parents held a similar view of their son, that there was a supernatural pull on his life – not only Jimmy, but Jerry Lee as well, who had already “fallen away” and made compact with Satan. Though Jimmy may have gently asked for permission, helpfully suggesting that it would be alright because he had been able to resist temptation for years, going to the movies “wounded” his parents because it meant he was also rejecting God, even joining Jerry Lee as a disciple of Satan.

I stood for what seemed like an eternity. Daddy never said a word. Finally I walked out of the house and went to the movies with my cousin, Mickey. But I was sick about it the moment I sat down in the dark theater. Halfway through the movie, I got up abruptly and stumbled out into the afternoon sunshine. I was confused and bewildered. My insides were aching. But I was afraid to ask God to forgive me, for that would mean confessing something was wrong in my life. I put ,y Bible in a dresser drawer. I no longer went outside to my prayer altar behind the house. Miserable, I had just enough religion to keep me from overt sin, but not enough to give me any joy.

The next step was predictable. I tried to see how deep in sin I could slide. Jerry Lee and I began breaking into local stores and stealing. Little things at first, but planning, always planning for a big heist. The next day we would go by the police station and ask if they knew anything about the robbery. My. Harrison, a pleasant gray-haired man in his early fifties, had replaced Pa Swaggart as police chief. “No,” he would say, “we haven’t caught ‘em yet but we’re on their trail right now.”

“How many do you figure are involved?” we would ask.

“Oh, it’s a gang, at least,” he would say with great assurance.

It was a lark to us. We thought we had put one over on the law. I couldn’t count the times we walked off laughing after one of those talks with Mr. Harrison. We even stole some scrap iron from Uncle Lee’s own backyard and then sold it back to him. Uncle Lee had often boasted nobody ever “took him” in a busines deal. But Jerry Lee and I had (46-47).

Jimmy’s sins continued to escalate. They began to break into stores and warehouses at the edge of town, looking for easy money and anything of value, taking what they could sometimes just for the thrill of getting away with it. Finally, they broke into one warehouse only to find bales of barbed wire. Even Jerry Lee had sense enough to know they were getting in over their heads, that there was no way to transport, use, hide, or sell a product that everyone in Ferriday would need but which two boys shouldn’t have in their possession. Jerry Lee wanted to leave, but Jimmy insisted and got angry. If they were going to keep committing crimes, they needed to commit to it whatever the quarry. Surely, there would be an opportunity to sell it eventually. Jerry Lee refused. Jimmy’s excess, his continual search for thrills even without thinking about it, was becoming dangerous. The two had a falling out, which was convenient for Jimmy after all. On his next break-in, Jerry Lee was caught and arrested. He didn’t have anyone in the family who could clean things up; instead, he had to have his father bail him out and pay back the damage. Jimmy, not there for this particular crime but having left Jerry Lee with the idea that excess and crime were worth the risks the two had been taking, claimed to know nothing about it. Jerry Lee, ever the embarrassment to their family, was left to take the fall.

There may have been a less spiritual reason for Jimmy’s fever for crime. It may have been more practical that he spiritualized. Sun, Jimmy’s father, had wanted to be a lawyer before Jimmy was born. His attempt at becoming a boxer had quickly ended; he may have been barrel-chested, but he was glass jawed. He had turned to law, wanting to follow the example of Governor Huey Long and restore the Swaggart name. Or, more simply, to make money.

In the South, titles and education, marriages and hard work do not matter like they do in other regions of the country. In the South, the only things that have ever mattered are land and money. How one acquires them is inconsequential. In fact, in Louisiana especially, illicit gain is expected and part of every political bargain made. No one does anything out of the goodness of their heart. Southerners love a good story from the Romantic tradition, one with nobility, holiness, and true love, but sin is the salt on the rim of the glass, the cherry on top of the sundae, the spice of life. It’s expected. So while Sun may have talked about pursuing law, giving his family a good name, going further than Uncle Lee, and using his imagined wealth to bring the entire family upwards, he instead became a painful spendthrift, too miserly to make the initial investment in education. He harassed Jimmy and made the boy pay for his own meals, even as a boy.

Ostensibly, every penny should have gone to saving up enough to buy their way out of poverty. In the South, sharecroppers like the Swaggarts, Gilleys, and Lewises were hardly above slaves and had been born into such an estate. In 1911, Jimmy’s great-grandfather Richard died at the age of 60. For years, Richard had been scrabbling a hard life in Monroe, building a farm. When he died of influenza, his wife followed soon after. The couple left four children, all of them barely grown. Within a year, the farm was lost. The children were orphaned and destitute. One of them, W.H. or “Grandfather Willie”, held a lifelong distrust of lawyers as a result of their seizure of the land, the farm, the lives of the Swaggart family. These events psychologically stamped the entire family. Sun would have grown up knowing the legend of how his father and family lost their place in the world to lawyers; his desire to become one himself as a means to acquire land and restore the family is an easy connection to make. Less obvious are the ways in which these events were framed by W.H., who would eventually rise to become the sheriff of Ferriday, lost in the narrative Jimmy would later construct of a tongue-talking grandmother, W.H.’s wife, and musical parents. The tragedy and sorrow, the weight of the loss, the pursuit of the unattainable, the viciousness all converge into a demoralizing milieu for Sun and his “pathological fix on money” even as he came up against his own financial and intellectual limitations.

“Sun Swaggart gets 99 cents out of every dollar,” his relatives said. He was always looking for ways to make money, and hoarding it became an obsession. He would show up at Irene Gilley’s house nearly every day for a cup of tea or coffee, often at mealtime. “Aunt Reenie,” as she was known, was a good cook, and manners required that you always offered food to a visitor, even a penny-pinching nephew. But reciprocity was hard to come by. Once, Aunt Reenie dropped in on Sun and his third wife, Dorothy. They sat for a while chatting, and no one offered Irene refreshments. Finally, she asked for a cup of tea. Sure, Sun said, if she would give them some money, Dorothy would go out and buy some tea bags. (Seaman 62).

Sun would convince Jimmy and his cousins, Jerry Lee, Mickey, David Beatty, and whoever else they could convince to help them to hunt furs or pick cotton, but he would pay poorly, barely giving them enough to see a movie. Whatever friends Jimmy and Jerry Lee has recruited soon learned a day’s labor wasn’t worth the pay if Sun was the one holding the purse. He kept the rest in a sack hidden in the bedroom. Jimmy, naturally, had to continue working anyway and had to work harder to make up for the “laziness” of the other schoolchildren and family members. Biographer Ann Rowe Seaman was able to meet with and interview several family members for her 1999 biography of the evangelist. Practically every interview she conducted corroborates the next, that Sun made life hard for his son.

“If you’d ever go and eat dinner at his house? He’d always act like he hated to see you eat. He’d watch you the whole time,” said one of Jimmy’s cousins.

Jimmy was an industrious child, but the clan tsk-ed because Sun made him buy his own clothes. Minnie Bell’s sisters and other family members whispered about it.

“Sun’s a money-lover,” said Cecil Beatty. “If you worked for Sun Swaggart and you made fifty cents a day, you were doin’ good. What he cared about was makin’ money. And right up to this hour, this second, he’s the same as he’s always been.”

Minnie Bell gritted her teeth under the disapproval, but she never defended Jimmy against Sun. Even her sister, Viola Beatty, with her sharecropper husband in their two-room shack at neighboring Swampers, Louisiana, managed to buy their five children one set of school clothes a year. But everything Jimmy was given or denied was pitilessly traced back to some chore he had done or not done. Nothing was free – he learned that early.

“It wasn’t fair to do Jimmy that way,” his cousin David Beatty overheard his parents sat more than once. “He was their child, and they should have bought him clothes… Uncle Sun was real mean to Jimmy in a lot of respects.”

Sun demanded obedience, and Jimmy didn’t dare talk back to him or he would find himself sprawled on the floor. As a cousin put it years later, “What our parents called discipline would be called child abuse today.”

She remembered a threat Sun would hiss at Jimmy, nieces, and nephews, or Jimmy’s playmates when he got mad: “I’m gonna get in my car and run you over.”

“If [Jimmy] challenged his father,” she said, “Uncle Sun would… just deck him.”

“Jimmy was scared to death of his daddy,” another cousin said. “He couldn’t run with the crowd. Uncle Sam wouldn’t let him.”

“When Jerry Lee and Mickey and Cecil Wayne and all that bunch was running around, the only one that wouldn’t bum around with them was Jimmy Swaggart,” said a longtime family acquaintance, Frank Rickard. “Jimmy Swaggart was tucked up under his mama’s tail.”

The anger Jimmy had to repress tumored into bouts with depression later in life. These bouts became complex, and became entangled with sexual desire. He would call them “demon oppression” and “attacks of Satan” (Seaman 62-63).

Jerry Lee’s arrest and the subsequent shame it brought to the family bonded he and Jimmy together. The two had been pushing one another to new heights for years and, yes, things had taken a wrong turn. Jerry Lee suffered as a result. He never betrayed Jimmy, though. They were in it together. Jimmy needed the wild abandon that Jerry Lee provided every bit as much as Jerry Lee needed the appearance of goodness that Jimmy provided. Together, they had begun to forge a new life. As Jimmy writes, “At times, alone in my room, I actually prayed, ‘Lord, please leave me alone. I don’t want to preach.’ I no longer considered myself a Christian. I refused to attend church unless daddy forced me. Mama, daddy, and Nannie were heartbroken over me” (To Cross a River 48).

Around this time, Jimmy began boxing at school. As Jimmy has often explained, his desire was to become the heavyweight boxing champion of the world. This short-lived interest was shaped in the shadow of his father’s failed career in the ring. The boy probably wanted to learn how to defend himself from his father, who had wanted to be a boxer more than anything. Sun’s “discipline” of his son necessitated that Jimmy learn to stand up for himself for when the appropriate time came. While he loved his father, even feared him, there was a distance growing between them as Jimmy, like all of his cousins and classmates, began to recognize the difference between discipline and debasement. New reforms were taking place in education across America. In Louisiana, these reforms gave the law cause to step in sometimes for truancy to make sure children actually went to school instead of working the fields with their parents. Schools began paying attention to the telltale signs that something was the matter at home. Nurses and rotating doctors would attend to schools as satellite offices of their own practices. And it was in these conditions that Jimmy learned he had an irregular heartbeat, one that would prevent him from being allowed to participate in sports.

All of the school’s athletes were required to take a preliminary physical. The doctor examining me looked strange after placing his stethoscope near my heart. He placed the cold instrument there again.

“What’s the matter?” I asked looking down at his furrowed brow.

“Your heart is beating fast,” he replied tersely. “Have you been running or something?”

“No,” I answered. “How fast is it beating?”

“Over a hundred times a minute,” he responded.

“What’s normal?” I questioned as an uneasy feeling began to settle on me.

“Seventy to eighty.”

“Well, what can I do about it?” I asked.

He looked at me seriously. “I’m sorry to tell you this,” he said, “but I can’t approve you to participate in any sports for school. If I did, this rapid heartbeat might become fatal” (49).

By high school, Jimmy had already developed the barrel chest and form of a boxer, but had to way forward, no avenue out of his abusive home without being allowed to play sports. He cried in the locker room after he was told, once more crying out to God. This was God’s way of blocking every avenue to him, he knew, except for the call to ministry.

While the entire family claimed Jerry Lee took to the piano immediately, possessed with a supernatural gift, Jimmy would sometimes claim his talent had to be developed. Presumably, Jerry Lee helped further along Jimmy’s abilities with music but both of the cousins have told stories about “Old Sam”, an elderly Black man who did odd jobs for white families in Ferriday during the day and was known to play spirituals, jazz, and popular songs on the piano. The boys studiously watched how Old Sam’s left hand would glide across the keys. “Jerry Lee and I were literally hypnotized by what we called Sam’s walking left hand. It seemed to dance over the keys. Many times, we sat for hours listening to Old Sam play.” Notably, both men would claim that Sam never taught them to play. There is a hint of latent racism in this; despite their poverty and the hardships they endured, at least they never sunk so low as to have been taught anything by a Black man.

He never actually sat down and taught us, but we would watch what he was doing and learn it. Jerry Lee and I both began to develop our left hands to play somewhat as Old Sam did. We were together every day and playing the piano most of the time. In fact, the keys on Jerry’s piano ultimately wore down to the wood and turned swayback like an old, worn-out mule. My upright piano wasn’t worn that much even though he and I were constantly playing it. I played the bass and Jerry Lee would do the treble at the same time. For a little added spice, we crossed our hands in the middle.

Occasionally we would both break down and go to church – but only to play the piano. The folks always requested us to play church favorites such as “Jesus Holdeth My Hand,” “Just a Little Talk with Jesus,” “Keep on the Firing Line” and the like. We always managed to work in Old Sam’s rhythm pattern. The people always loved it, but the pastor didn’t like the rhythm. “You can play in church any time you want,” he admonished us after one service, “but don’t play it with that rhythm. I won’t have it” (To Cross a River 52-53).

The two began entering talent shows and contests until they became recognizable in the area and were turned away. They said that judges would not even allow them to play, despite the demands of the crowd to hear them, because their skills – whether together or apart – were so established that other players would drop out or would play, but would claim they were judged unfairly. Their mere presence would prove frustrating for other players and especially the judges.

One night in nearby Jonesville, a little over sixteen miles away from Ferriday, something strange happened that changed the course of Jimmy’s playing. He and Jerry Lee were allowed to play at an show where only adults were allowed to play. “The show was for dance bands and singers – people who made their living in the business. They agreed to let us enter because of our reputation, even though we were only in our early teens. Instead of allowing us to play together though, the judges permitted us to do one song apiece.” Jimmy began to play

when this strange feeling came over me. I was able to do runs on that piano I hadn’t been able to do before. It seemed like a force beyond me had gripped and charged my body. My fingers literally flew over the keys. For the first time in my life, I sensed what it felt like to be anointed by the devil. I don’t know any way to describe it. It was unlike anything I had ever experienced in my life. I knew it wasn’t from God.

The huge crowd filling that auditorium stood up and cheered wildly. People screamed and whistled. Applause filled the air. I could sense that strange power rushing over me. A chill flickered up my back. I was scared. Although backslidden, I remembered what I had promised the Lord years before, that I would never play for the world.

After I finished, Jerry Lee sang and played, drawing the identical response from the crowd. That same demonic anointing I experienced was also on him… A few months later Jerry Lee opened at the Wagon Wheel, a night club over in Natchez. It wasn’t a question my cousin had to reflect over. And his parents readily encouraged him in that direction. To them, it wasn’t a question of sin. It was just another step along the way until Jerry Lee made it into the big time (53-55).

Jimmy, scared and bound to the promises he had made to God as a child, began working at his grandfather’s store. “The deeper Jerry Lee got into the night club circuit, the more I drew back.” After he had retired from the Sheriff’s office, Pa Swaggart opened a grocery with Sun. Jimmy worked there, sometimes cleaning and sometimes working the meat counter. One day, a nightclub owner from Natchez walked in asking to speak with Jimmy. He had heard about the young man who played with Jerry Lee on the local music circuit. Would Jimmy like to play a few gigs of his own, like his cousin? Jimmy hesitated, wanting to play, wanting to make something of his life, but he was still afraid of what had happened in Jonesville. He turned down the offer to everyone’s surprise, especially his grandfather who had quietly been watching the pushy nightclub owner desperately trying to recruit another sure thing for his stage. He offered Jimmy four times what he made at the grocery store, but still the boy couldn’t bring himself to agree. “All I knew was I had made a promise to God, and I was afraid to break it.”

Mickey had also begun to play by this point, in the shadow even then to his older cousins. Still trying to bring Jimmy with him, Jerry Lee suggested they form a trio. Something. Anything so they could stay together and make a name for themselves. Mickey, like Jimmy, declined. He saw the kinds of performances Jerry Lee was doing and was also afraid of where it might lead, agreeing that he would play with them in church but wasn’t interested in playing clubs like Jerry Lee was doing. Crowds were drawn to Jerry Lee, “as if by some supernatural power” but Mickey and Jimmy were sons of praying parents who were not as supportive of the circuit as the Lewises. Jerry Lee’s parents were not exactly enthusiastic about where their son’s life was taking him. While they encouraged him and his talent, even begrudgingly accepting the fame and money he was bringing home, Jerry Lee’s life had taken a turn for the worse from the time he began playing in nightclubs. He always seemed to be in trouble. There was his first marriage, a rotating list of women with loose morals – some of them even married – and of course the drinking, until the Lewises had had about enough. When he was fifteen, his parents sent him off to Waxahachie in the hopes of straightening him out, a last-ditch effort that would spectacularly fail. Looking back, Jerry Lee would say this was the moment he gave himself over to his music. “The truth of the matter was Jerry Lee played songs in chapel the same way he had been playing in night clubs. The school’s teachers were outraged, and refused to let him continue” (59). A year later, Jerry Lee would marry for the first time and quickly be served with divorce papers. Shortly thereafter, before the divorce was finalized, he would marry again. Poverty was no longer the only issue bringing shame to the family.

Moving in a completely different direction, the Swaggarts continued making decisions in stark contrast the Lewises. Namely, the Swaggarts were becoming more religious. When Jimmy was fifteen, Sun and Minnie used the connections they had made as traveling church musicians to begin preaching along with their singing. Sun preached several revivals throughout the area, focusing on isolated churches where no “full gospel” or Pentecostal church existed before. He felt called to help communities form congregations and construct new buildings, finding success and eager crowds for such an empowering message. Together, Sun and Minnie Bell performed for churches who were unaccustomed to talent like theirs – and preaching too! Jimmy’s sister Jeanette often traveled with them, playing the accordion, and they even managed to convince Jerry Lee to come along and play on occasion. Despite the family tradition, Jimmy refused to go with them. When his parents forced him to go with them, he would agree to play but would either play poorly, intentionally, or would perform gospel music in a “worldly” way to annoy them until they stopped asking. Sun and Minnie could no longer deny their own call to ministry. Sun sold his stake in his father’s grocery store. Then he went a step further. He and Minnie Bell sold their house. They were going into full time ministry. It was the kind of upheaval at such a frustrating time, further compounding the frustration Jimmy felt about his own call to ministry.

I knew something like this would happen. I began to cry – partly in anger. “Please don’t, daddy,” I pleaded. “You’ve already got a church at Hebert. You can continue working and pastor the church, too. You just can’t give all of this up”… The thought of daddy going full-time into the ministry was absolute torture for me. For years after that, when I had to fill out a school form listing my parents’ occupation, I left it blank. I detested the thought of him being in the ministry. I didn’t want to be a PK – a preacher’s kid. I didn’t want to hear any more about God or church. I wanted to be left alone – to live my life my way (61).

Sun turned the church he had been pastoring in Hebert over to someone else and began holding tent revival meetings in Wisner, a half hour away to the North. Compared to Wisner, Ferriday seemed huge. It was one of the isolated areas Sun had tried so hard to build something new in, something Pentecostal. Many were saved and filled with the Holy Spirit, a church building went up in three months, and the ministry flourished. To his growing anger, Jerry Lee softened and agreed to play at the church along with Jimmy’s sister, Jeanette. Hadn’t Jerry Lee given up on God and playing in churches? Hadn’t that been what he had said after Waxahachie? “Then one afternoon Jeanette came home from the services and announced, ‘I saw the prettiest girl in church today.’”

Continued in Chapter 7