At the turn of the century, American religion was saturated with alternatives. The fragile denominations, long thought solid and transparent, were tinkling with danger. Tributaries of unique beliefs, cracks in the edifice of American Christianity, were threatening the safety of conservative beliefs. In the North, sermons supported economic interests, expressed a tolerant nationalism following the Civil War, and enshrined the privileged civility of Eurocentrism. But this veneer hid the lives of Americans who were either disinterested in the vague pietism of those inside the church or were already in it and intolerant of anyone who held loud views on anything. The nation was experiencing rapid expansion as many Americans moved West and those who stayed did their best to populate their communities with familiar, American ways of life. The center would not hold.

In the South, emphasis on theological truth was taking hold. It would be more authentic to say that religious communities were becoming more convinced of their rightness in opposition to all other claims. Churches split and split again over minor claims of no salvific importance. Denominations, specifically and especially the Southern Baptists, had to rewrite their origins to gloss over the anti-Gospel parts and be accepted as truly Christian – whatever that meant now after the Civil War – and be allowed to make claims to legitimacy. Though the denomination was founded on slavery, Southern Baptists began to claim that their differences from American Baptists were theological rather than political or racial as multiple documents, essays, sermons, news pieces, and anecdotal evidence overwhelming attest. Claims to theological error were rampant, fired back and forth in a spiritual civil war unto itself.

Folk religion may have taken hold in the North by way of Transcendentalism or philosophy or simply an effort to bridge the divide between churches, to engage in ecumenical dialogue, but from the perspective of Southerners, this amounted to syncretism. Presbyterians and Methodists were lowering the barriers to biblical truth, eroding their witness. Calls for doctrinal purity and revivalistic calls for repentence by clergy toward clergy further shaped the American religious experience.

For the Southerner, mainline denominations “up North” – Presbyterians, Lutherans, Congregationalists, even Methodists – in Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, or New York, were simply apostate. It was as simple as that. The Americanism of their ministers was a false nationalism, even a Cananism, because the apostate nation and its cabal of clergy had denounced State’s Rights for Nationalism, had forbidden the biblical institution of slavery to embrace an “unbiblical” disavowal of class systems, and encouraged the advance of women’s rights when the apostle Paul forbade women from speaking. The most egregious violation of scripture by Northerners – apart from rejecting the implicit divine order of State’s Rights and individualism – was the Social Gospel that had taken over the bigger cities of Chicago, New York, and Boston. The Social Gospel was just another threat to America. Foreigners, like the Blacks, needed to be put in their place and reminded regularly that they didn’t have a claim to this nation. The Truth Church was the one that the Lord God Almighty had seen fit to locate in the South, where the gospel was simple and Whites were the dominant race. People didn’t need some convoluted muckety-muck theology. There were fundamental truths that Christians could agree on, and there they were in the Bible. Pastors needed to focus on the Bible, not get involved in politics, and those high-nosed ivory tower theologians and so-called experts should just set aside their arrogance. This was God’s Country, not theirs.

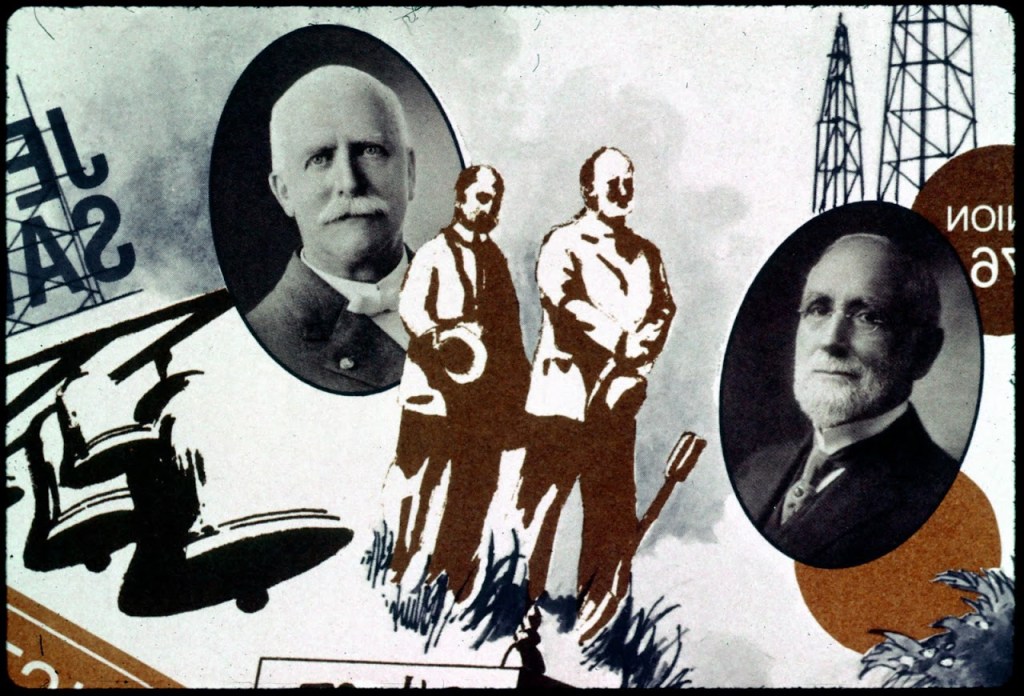

What America needed was an old-fashioned revival. If God wouldn’t provide one, one could be manufactured quite easily. The project was conceived in 1909 by California businessman Lyman Stewart, founder of Union Oil. Stewart was a devout Presbyterian and dispensationalist. He and his brother Milton provided funds to the Testimony Publishing Company of Chicago for composing, printing, and distributing a series of essays between 1910 and 1915.

By the end of 1915, there were 90 essays presenting “a new statement of the fundamentals of Christianity”, frequently targeting and taking issue with “liberal Christianity.” These essays are widely considered to be the foundation of modern Christian fundamentalism. It provided rigor, grit, and a common language for a movement that took issue with the softer, more compassionate tone that Christianity had been taking in recent decades. Well-funded as they were, the essays had an immediate and broad impact with every subsequent declaration or denunciation. There were different authors, ultimately sixty-four of them, representing the major Protestant Christian denominations in the United States; this gave the appearance of widespread acceptance by denominations uniting to confront liberalism in their churches. The essays were mailed free of charge to ministers, missionaries, professors of theology, YMCA and YWCA secretaries, Sunday school superintendents, and other Protestant religious workers in the United States and other English-speaking countries; over three million volumes (250,000 sets) were sent out before the essays were bound and republished as a collected work for the following generation, further reinforcing and legitimizing what they had been taught.

The essays defended classical Protestant doctrines, of course. This was their baseline. They were also noted for their sustained attack on what they presented as non-Christian or unbiblical teachings. Higher criticism, liberal theology, socialism, modernism, atheism, evolution, education, spiritualism, and “cults” like Roman Catholicism (“Romanism”), Christian Science, Mormonism, Millennial Dawn (whose members were sometimes known as Russellites, but later split became Jehovah’s Witnesses) were each, in their turn, targets of The Fundamentals. Divisive and carefully targeted to change the face of Christianity, one of the most notable consequences of The Fundamentals was the animosity and acrimony that began to appear between denominations beginning at the start of the Twentieth Century. Denominations often worked together, especially at the local level. Churches supported one another at times and often scheduled events to complement one another’s calendars. A revival at one church, for example, might compel another local church to move their own back a week. A bake sale would respectfully be removed if one more familiar to the community were taking place. It might seem strange to a Methodist to know that their neighbor was eager to baptize their newborn infant. Then again, the Methodist would think to themselves, they have their own unique beliefs also. What mattered was a shared and reciprocal appreciation of one another’s uniqueness if understanding were not possible. After The Fundamentals began circulating, one can see churches pulling away, retreating within themselves, siloing. Churches become rivals and enemies with one another in pursuit of the truth. Even one’s own denomination could not be trusted if they didn’t teach and preach the basics. Anything else amounted to the pedaling of filth and rot, corruption and degradation, in the name of God.

With the emergence of radio and television, stations were required to set aside time for religious broadcasting and one can see and hear a considerable amount of repetitiveness as different expressions of Christianity essentially parrot the baselines of the faith – salvation, church attendance, civic duty.

At the margins, whenever a minister begins to depart from the fundamentals of the faith, there was tentativeness. There was hesitancy and defensive posturing, an effort to explain one’s beliefs alongside those more commonly accepted. Confronting the enduring (and inaccurate) accusations made against the Roman Catholic Church, American Bishop Fulton J. Sheen became a leader in religious broadcasting with his clear and methodical approach to dispelling false claims made in The Fundamentals and by its broad audience. For 20 years as “Father Sheen”, later Monsignor, he hosted the night-time radio program The Catholic Hour on NBC (1930–1950) before moving to television with Life Is Worth Living (1952–1957) and The Fulton Sheen Program (1961–1968). Sheen’s success was how he differentiated his programs, patiently working through the Catechism of the Catholic Church instead of offering extemporaneous preaching. Sheen demystified Catholicism by anchoring the faith in philosophy and reinforcing Americanism. Though Sheen was doing something different than other broadcasters who continued to repeat The Fundamentals, he spent decades responding to the spurious claims that were made against Catholicism, asserting its Americanism, explaining the biblical roots of practices and theology, and exhibiting a tremendous amount of patience toward critics.

It was this environment from which the Pentecostals would emerge and would, by the end of the century at least, thrive. Blame and distraction have always been part of Fundamentalism and, by extension, their inheritors – the Evangelicals, the Pentecostals, and the Far Right. Whenever they are criticized, these groups pull from a long list of rivals or groups they see as rivals and begin attacking. What about Roman Catholics who pray to Mary and the saints? What about the Baptists who reject “the Full Gospel”? The weirdos like the Mormons, Feminists, school boards, libraries, the Episcopalians were a threat to America right along with the liberals, secular humanists, the educated, Communists, Socialists, nameless and faceless “elites”, gays with their “homosexual agenda”?

By the Eighties, facts no longer mattered to Fundamentalists or their progeny, Evangelicals. Love for God, decency toward the people of God, care for the Earth and its resources, none of these mattered by the Nineties to either group. With the new century, Fundamentalists added Muslims, yoga, rock music, toy companies, and children’s television to an expanding list of enemies, false religions, and secret societies. evangelicals were right there with them, expressing false claims about Islam and Muslims, asserting long-debunked claims about Russia “fulfilling” biblical prophecies, focusing on self-improvement (rather than self-denial as taught in the Christian Scriptures) and a never-ceasing demand for money. With the election of Donald Trump, pizza parlors and a “Deep State” overseen by the Democratic Party had become new manifestations of an ancient evil. Evangelicalism and Fundamentalism had become intertwined with one another, proclaiming conspiracy theories, falsehoods, and “alternative facts” as the Gospel. Instead of being seen as something unique and apart from The Fundamentals, logical and spiritual fallacies had fulfilled exactly what The Fundamentals were designed to accomplish. It had though, in a twist of irony, weaponized the tendency of Christians to engage in social improvement toward toward a kind of social destructiveness, emphasizing how everyone else was wrong and how biblical literalism, harshness, meanness, and regressive attitudes were proof of salvation.

The increasingly unbiblical and antibiblical positions that the essays proposed were, as they said themselves, a new tableau, a new agenda, “a new statement of the fundamentals of Christianity”, one which bore no resemblance to historical, textual, or creedal Christianity. By “proof-texting” or using passages of scripture in isolation, apart from context, The Fundamentals claimed to present the “basic” or “timeless truth” of Christianity in reaction to the proliferation of new religious movements that emerged out of the Second Great Awakening, movements that were continuing to flourish and, in many ways, reinforce as much as challenge the teachings of the Church.

Fundamentalists were correct that syncretism, or the amalgamation of different beliefs was becoming a part of the Church in faith, practice, and theology. New movements continued to erode and replace Christian practices from within; continental philosophy and literary criticism were changing a traditional reading of scripture without; the popularity of movements and their use of the Bible to define and promote new, decidedly different teachings presented not only an alternative to traditional Christianity but in some cases a threat. Christian Scientists, for example, bear the name of Christianity. Founded in 1879, they were part of the movements that emerged from the Second Great Awakening and, along with many Christian movements, believe in the authority of the Bible over a believer’s life, in the salvation offered by Jesus Christ, in the resurrection of Jesus, and in a coming day of judgment. They observe Christian holidays like Christmas and Easter. Their most remarkable belief is that physical healing is possible through prayer from sickness as well as disease. So far, this new religious movement or “cult” meets the major tenets of traditional Christianity. Baptists, Methodists, Catholics, even Pentecostals all believe and practice these same things. In many ways, a faithful Christian would not be able to distinguish their own beliefs from those of a Christian Scientist. Yet, the Fundamentalist would point out that Christian Scientists are not Christian but instead something else entirely – cultic and outside of God’s providence of salvation – because they reject the deity of Jesus (though, splitting theological hairs, not his divinity). Instead, Christian Scientists see Jesus’ life as one exemplifying a divine sonship that belongs to all men and women as God’s children. This difference may have been minor, even inconsequential to many Christians until The Fundamentals demanded adherence to traditional Christianity and a Trinitarian theology to be valid. This difference, while minor, is one that Christian Scientists do not adhere to; their emphasis on faith (rather than medicine) quickly continues to widen the cleave. For the Fundamentalist, this detail damns all Christian Scientists to Hell, their beliefs those of a false religion, one that damns people rather than saves them though, again, they believe in the salvation offered by Jesus’ death and resurrection. For the Fundamentalist, what matters most is not Jesus’ life and teachings but his Godhood and death. Jesus is not a god, but the God of scripture. Anything else is a lie of Satan.

For many years, despite its popularity in rural areas, Pentecostal teachings were dismissed. It was seen as foolishness by many believers, an expression of poor education, popular only among the ignorant. For others, it was so immediately different from traditional Christianity that it was seen as evil, “strange fire” in churches that needed to be extinguished. Claims to the miraculous, to God’s activity in the believer’s life, to physical healing, were heavily scrutinized when they were not dismissed outright. As for tongues, who had ever heard such nonsense? People walking around speaking a language they couldn’t understand – even one allegedly spoken in Heaven – made no sense. Jesus may have been able to walk around healing people, but only because he was the Son of God and not because he was Pentecostal.

One of the first innovators of radio ministry, Aimee Semple McPherson, had to dial down her emphasis on tongues, prophecy, and spiritual gifts even as her ministry became defined by the dramatic and such activites. Oral Roberts, a popular healing revivalist, also downplayed his belief in tongues when his ministry became the most recognizable and high-profile example of Pentecostalism in America. At the local level, some Pentecostals demurred or sidestepped questions whenever they were asked. Explaining the activity of God to those who didn’t want to believe in it was like tossing pearls in a pig sty. It was a waste of time and only made things messy if it didn’t ruin them outright. Whether at the denomination or individual level, ministers simply did not wish to run afoul of traditional Christianity or find themselves the subject of another entry in The Fundamentals.

The Assemblies of God is one part of the Pentecostal spectrum. Parham managed to stir up a great deal of Pentecostal groups, to raise awareness and give attention to them, to bring together the disparate parts that needed to be assembled. Still, his goals, whatever they may have been, were ultimately left unfulfilled. Parham emphasized speaking in tongues, of course. He believed in healings along with Millennialism exemplified by the millennial “prayer watch” he encouraged his students to engage in as they entered the new century. He believed in personal revelation and, at least occasionally, seemed interested in empowering people of color, women, and the lifting up of the disenfranchised.

Like the Fundamentalists who were developing literature, teachings, and outlines to reorient Christianity, Parham was engaging in his own selective proof-texting and buffet-style theology during the same period. In this way, he was unremarkably derivative. Yet to his credit, he managed to pull together parts of several pre-existing ministries and reforge them into something new; his greatest contribution to Pentecostalism was his ability to pull together teachings and experiences from the Second Great Awakening, in some instances revivvify them, and place them into a biblical framework.

Parham managed to attract followers of John Alexander Dowie, a faith healer who had established an entire city of believers in Zion, Illinois. Dowie had emphasized miracles and physical healing; his ministry collected braces, walkers, protective headgear, glass eyes, and various other accessories from those he claimed to have healed. They were displayed on the walls of his church as proof that people were genuinely healed by faith. Parham’s emphasis on healing and the miraculous remains central to Pentecostal experience and religious expression.

Tongues were not new. Parham had heard of believers who prayed and spoke in tongues during his travels; these scattered stories are what convinced him to hold the prayer meetings at his school in Topeka, Kansas, where he emphatically encouraged his students to wait for the filling of the Spirit. Tongues were seen as the initial evidence of God’s Spirit in the life of a believer, but what this meant is more complex than merely a new language, whether known to humans or only to angels. Parham believed there was more to the presence of God’s Spirit in the lives of believers. Tongues were the initial evidence, but evidence of what he and the new movement continued to try and articulate. Later, after the Azusa Street Revival, tongues would be affirmed as evidence of the baptism in the Spirit of God in an effort to align the new religious movement with key figures like John Wesley, the Holiness Movement, and Presbyterianism. This baptism, it was explained, was a subsequent and distinct baptism from the water baptism familiar to other Christian groups. It is, as the Assemblies of God defines it in the seventh of their Sixteen Fundamental Truths, “the enduement of power for life and service, the bestowment of the gifts and their uses in the work of the ministry.” The language of the Holy Spirit is, not surprisingly, the key to understanding Pentecostalism and its inheritors across Charismatic or “Full Gospel” churches.

The Pentecostal movement, at least as it is theologically identifiable today, has its beginnings not with Parham who placed emphasis on gifts and empowerment, but British perfectionism and other early attempts at charismatic movements emphasizing the condition of one’s internal witness. The most well-known of these movements were the Methodist Holiness Movement, the Catholic Apostolic Movement of Edward Irving, and the British Keswisk “Higher Life” Movement.

Parham and Seymour’s adoption of different labels in different contexts helped them continually revise their own history. What appeared to be a spontaneous outpouring of God’s Spirit in Topeka, Kansas, on January 1, 1901, was instead the inheritance and synthesizing of these movements, polished and refined in the retelling. Notably, “the most important precursor to Pentecostalism was the holiness movement that issued from the heart of Methodism during the 18th Century” according to Vinson Synan in his The Century of the Holy Spirit: 100 Years of Pentecostal and Charismatic Renewal (2001). There, he walks through the important developments of what would later become recognizable as the Pentecostal experience.

John Wesley, an Anglican priest, experienced his evangelical conversion in a meeting at Aldersgate Street in 1738 where, as he said, “my heart was strangely warmed.” This he called his “new birth.”

From Wesley, Pentecostals also inherited the idea of a crisis “second blessing” subsequent to salvation. This experience he variously called “entire sanctification,” “perfect love,” “Christian perfection,” or “heart purity.” Wesley’s colleague John Fletcher was the first to call this a “baptism in the Holy Spirit,” an experience that brought spiritual power to the recipient as well as inner cleansing.

In the 19th century, Edward Irving and his friends in London suggested the possibility of a restoration of the gifts of the Spirit in the modern church. This popular Presbyterian pastor led the first attempt at “charismatic renewal” in his Regents Square Presbyterian Church in 1831 and later formed the Catholic Apostolic Church. Although tongues and prophecies were experienced in his church, Irving was not successful in his quest for a restoration of New Testament Christianity.

Another predecessor to Pentecostalism was the Keswick Higher Life movement, which flourished in England after 1875. Led at first by American holiness teachers such as Hannah Whitall Smith and William E. Boardman, the Keswick teachers soon changed the goal and content of the “second blessing” from the Wesleyan emphasis on “heart purity” to that of an “enduement of spiritual power for service.” D.L. Moody was a leading evangelist associated with the Keswick movement.

Thus, by the time of the Pentecostal outbreak in America in 1901, there had been at least a century of movements emphasizing a second blessing called the baptism in the Holy Spirit. In America, such Keswick teachers as A.B. Simpson and A.J. Gordon also added an emphasis on divine healing.

The first Pentecostal churches in the world originated in the holiness movement before 1901: the United Holy Church (1886), led by W.H. Fulford; the Fire-Baptized Holiness Church (1895), led by B.H. Irwin and J.H. King; the Church of God of Cleveland, Tennessee (1896), led by A.J. Tomlinson; the Church of God in Christ (1897), led by C.H. Mason; and the Pentecostal Holiness Church (1898), led by A.B. Crumpler. After becoming Pentecostal, these churches, which had been formed as second-blessing holiness denominations, retained their perfectionistic teachings. They simply added the baptism in the Holy Spirit with tongues as initial evidence of a “third blessing.”

Healing, tongues, and the “baptism of the Holy Spirit” are major teachings that distinguish the Assemblies of God from other, more traditional expressions of Christianity. In many respects, the impact of Pentecostalism generally and the Assemblies of God specifically reshaped Evangelicalism by moving it away from Fundamentalism. Popular media ministries like Swaggart’s and the theological curiosity they inspired had such an impact on global expressions of Christianity during the latter half of the Twentieth Century that denominations which previously castigated the emergence of Pentecostalism and ridiculed ministers now warmly embrace them. As Thomas R. Schreiner details in Spiritual Gifts: What They Are and Why They Matter (2018), there are “strengths and weaknesses” to the Pentecostal movement.

Positive: What We Can Learn from Charismatics

1. “Spirit-Empowered Living. Emphasis is laid on the need to be filled with the Spirit and to be living a life that one way or another displays the Spirit’s power.” Sometimes we as evangelicals tend to ignore the Holy Spirit, and charismatics remind us about the third person of the Trinity and the need to be filled with the Spirit.

2. “Emotion Finding Expression. There is an emotional element in the makeup of each human individual, which calls to be expressed in any genuine appreciation and welcoming of another’s love, whether it be the love of a friend or a spouse or the love of God in Christ. Charismatics understand this, and their provision for exuberance of sight, sound, and movement in corporate worship caters to it.” Right doctrine is important, but so is our experience with God. Sometimes we stress right thinking but neglect other dimensions of what it means to be human.

3. “Prayerfulness. Charismatics stress the need to cultivate an ardent, constant, wholehearted habit of prayer.” How crucial as Christians it is to be in communion with God, and charismatics remind us of our personal relationship with God.

4. “Every-Heart Involvement in the Worship of God. Charismatics … insist that all Christians must be personally active in the church’s worship.” Worship isn’t the exclusive province of leaders, and charismatics rightly stress every-member worship. The body as a whole ministers to itself, and charismatics capture this biblical truth.

5. “Missionary Zeal.” Charismatics long to see others converted and saved to the ends of the earth. The Pentecostal/charismatic movement is worldwide the largest Christian movement.

6. “Small-Group Ministry. Like John Wesley, who organized the Methodist Societies round the weekly class meeting of twelve members under their class leader, charismatics know the potential of group.” The usefulness of smaller group meetings has been recognized by believers, as small group ministry has expanded.

7. “Communal Living.” Charismatics extend the sense of family in churches.

8. “Joyfulness. At the risk of sounding naïve, Pollyannaish, and smug, they insist that Christians should rejoice and praise God at all times and in all places, and their commitment to joy is often writ large on their faces, just as it shines bright in their behavior.” There is an openness to the Spirit and childlike trust, joy and humility, which is refreshing in this cynical world.

9. Real Belief in Satan and the Demonic. Many Christians say they believe in Satan, but charismatics take the demonic seriously.

10. Real Belief in the Miraculous. We still believe that God can do miracles, but sometimes we live like Deists, as if God weren’t active at all in the world. Charismatics don’t make that mistake.

Negative: Weaknesses in the Charismatic Movement

1. “Elitism. In any movement in which significant-seeming things go on, the sense of being a spiritual aristocracy, the feeling that ‘we are the people who really count,’ always threatens at gut level, and verbal disclaimers of this syndrome do not always suffice to keep it at bay.” Interestingly, this is the same problem we see in 1 Corinthians where those who spoke in tongues saw themselves as spiritually superior.

2. “Sectarianism. The absorbing intensity of charismatic fellowship, countrywide and worldwide, can produce a damaging insularity whereby charismatics limit themselves to reading charismatic books, hearing charismatic speakers, fellowshiping with other charismatics, and backing charismatic causes.” Charismatics are sometimes incredibly narrow so that there is little willingness to learn from other branches of Christendom.

3. “Anti-intellectualism. Charismatic preoccupation with experience observably inhibits the long, hard theological and ethical reflection for which the New Testament letters so plainly calls.” The emphasis on emotions can slight and denigrate the importance of careful thought. Careful interpretation of Scripture and orthodox theology are too often ignored. In scholarly charismatic circles the inerrancy of Scripture is denied quite often, and in popular circles people may rely on revelations from God for their daily life, in effect denying the sufficiency of Scripture.

4. “Illuminism. Sincere but deluded claims to direct divine revelation have been made in the church since the days of the Colossians heretic(s) and the Gnosticizers whose defection called forth 1 John, and since Satan keeps pace with God, they will no doubt recur till the Lord returns. At this point the charismatic movement, with its stress on the Spirit’s personal leading and the revival of revelations via prophecy, is clearly vulnerable.” Some claim God speaks directly to them, and they aren’t open to any correction or questioning of such claims. The focus on contemporary revelation may compromise or even contradict the teaching of Scripture.

5. “Charismania. This is Edward D. O’Connor’s word for the habit of mind that measures spiritual health, growth, and maturity by the number and impressiveness of people’s gifts, and spiritual power by public charismatic manifestation.” In practice 1 Corinthians 13 — where our spiritual life is measured by our love for others — may be ignored.

6. “Super-supernaturalism. Charismatic thinking tends to treat glossolalia in which the mind and tongue are deliberately and systematically disassociated, as the paradigm case of spiritual activity, and to expect all God’s work in and around his children to involve similar discontinuity with the ordinary regularities of the created world.” Most of life is lived in the ordinary. We don’t live miracle-a-minute lives. The most important moments in our lives are often invisible to others and even to us.

7. “Eudaemonism. I use this word for the belief that God means to spend our time in this fallen world feeling well and in a state of euphoria based on that fact. Charismatics might deprecate so stark a statement, but the regular and expected projection of euphoria from their platforms and pulpits, plus their standard theology of healing, show that the assumption is there.” Many charismatics (though not all!) throughout the world espouse the health and wealth gospel, and it is clearly the most popular false gospel in the world. When we read the New Testament, it is apparent that God often calls upon his people to suffer, and the role of suffering in the Christian life is often neglected among charismatics.

8. “Demon Obsession.” Some see demons everywhere, and identify every sin with a demon. Also, the emphasis on “territorial spirits” in some circles is off-center and often quite speculative.

9. “Conformism. Peer pressure to perform (hands raised, hands outstretched, glossolalia, prophecy) is strong in charismatic circles.” People may feel compelled to have the same spiritual experiences, and we may measure how spiritual someone is by the emotions expressed or by physical movements.

10. Experience Centered. A danger in the charismatic movement and in evangelicalism generally is a focus on experience so that experience takes precedence over and trumps Scripture. Powerful experiences of God are a gift of God, but Scripture must play a foundational role so that experience is not accepted as self-authenticating. Experience is subordinate to Scripture so that experiences do not become the arbiter of what is permitted. Instead, Scripture is the final authority and experiences are only to be accepted if they accord with Scripture.

The legacy of Pentecostalism in America favors Parham, including his excesses. As much as it favors Seymour’s Azusa Street Revival with progressive intercultural, intergenerational, and positive inclusion of women in leadership, Pentecostalism in all its expressions continues to reconcile itself to the hidden racism of Parham. It is not always clear why this is, especially when Pentecostals in America continue to touch home base at Azusa Street and – at least rhetorically – aspire to diversity of race, culture, experience, and folkway. It is especially curious, given the biblical account of Pentecost in Acts chapter 2 of the Christian Scriptures.

Now there were staying in Jerusalem God-fearing Jews from every nation under heaven. When they heard this sound, a crowd came together in bewilderment, because each one heard their own language being spoken. Utterly amazed, they asked: “Aren’t all these who are speaking Galileans? Then how is it that each of us hears them in our native language? Parthians, Medes and Elamites; residents of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the parts of Libya near Cyrene; visitors from Rome (both Jews and converts to Judaism); Cretans and Arabs—we hear them declaring the wonders of God in our own tongues!” Amazed and perplexed, they asked one another, “What does this mean?”… this is what was spoken by the prophet Joel:

“‘In the last days, God says,

I will pour out my Spirit on all people.

Your sons and daughters will prophesy,

your young men will see visions,

your old men will dream dreams.

Even on my servants, both men and women,

I will pour out my Spirit in those days,

and they will prophesy.

I will show wonders in the heavens above

and signs on the earth below,

blood and fire and billows of smoke.

The sun will be turned to darkness

and the moon to blood

before the coming of the great and glorious day of the Lord.

And everyone who calls

on the name of the Lord will be saved.

It is hard to escape the legacy of White Supremacy in America after the Civil War. Politeness and continual reminders of tolerance, while less over than burning crosses and lynchings, can still be forms of racism. While Parham held very racist views and evidence points to him possibly being a member of the Ku Klux Klan, others found ways to be embraced without explicitly embracing racists. Aimee Semple McPherson benefitted from the support and protection she received from the Klan.

McPherson’s ministry in Los Angeles would not have been possible had it not been for the Azusa Street Revival, which was led by Blacks, Latinos, and Asians. Azusa Street’s legacy is that it “fulfilled” a biblical prophecy in ways that Parham’s school was unable to do. The casual historian might be inclined to see Parham and McPherson’s friendliness with the Klan as a product of the time. President Woodrow Wilson was allegedly a member of the Klan and took tremendous pride in showing D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation at a special White House screening in February of 1915. Still, McPherson’s ministry and nationwide popularity would not have been possible had it not been for progressive attitudes among those participating in Azusa Street, attitudes that played a significant role in the expansion of Pentecostalism and evidently made space for McPherson’s unique type of ministry.

Even as the Assemblies of God was being formed in Arkansas, the heart of the South, there was a curious openness to deconstructing race that is remarkably unlike Parham and very much like William J. Seymour. Shortly after the denomination was formed, Ellsworth S. Thomas (1866-1936) joined the Assemblies of God and it was recently discovered that he holds the distinction of being the first African American to hold ministerial credentials with the denomination. There are indications this went without complaint or that it was even noteworthy; he was one among many. Thomas’ name may have faded into obscurity except for when new information came to light a few years ago as the denomination, like many others in America, was compelled to address embedded racism in their practices and theology. The Assemblies of God virtually exploded once they were formed and, given their rapid expansion, were not prepared for the volume of paperwork. In 1917, Assemblies of God leaders asked existing ministers to re-submit applications for credentials because paperwork had not been kept during the earliest years of the fellowship. In his 1917 request for credentials, Thomas claimed that he was originally ordained on December 7, 1913, by Robert E. Erdman, a Pentecostal pastor from Buffalo, New York. Thomas transferred his ordination to the Assemblies of God in 1915, when the Fellowship was only a year old. He probably did not know that he was the first credentialed black minister of the denomination; his request and transfer of ordination went unchallenged and unquestioned. Records at the Flower Pentecostal Heritage Center illuminate the issue of race, showing that Thomas pastored a congregation in Beaver Meadows, New York, from about 1917 until about 1922. He remained an Assemblies of God evangelist for the remainder of his life, holding evangelistic meetings in the area around Binghamton, services in his home, and pastoring again briefly in 1926. He also was a regular speaker in the early half of the 1930s at two other black churches in Binghamton, Shiloh Baptist Church, and Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church.

The early acceptance, credentialling, and support of Black ministers is remarkable considering the denomination’s early leadership; despite the denomination’s efforts to align with Azusa Street and point to it as an influential moment in their origin story, the reality is that the public face of the denomination was overwhelmingly white and remained so from their founding in 1914 into the next century. While Pentecostalism, by its very nature, could not segregate and remain faithful to its claims of Biblical heritage, it would increasingly do so as it sought legitimacy from those who subscribed to The Fundamentals, which hollowed out and reshaped much of American Christianity.

Women have a similar “place” in Pentecostalism. It is not always clear what role women played in the history of Pentecostalism and much of the history of the Pentecostal Movement has, inconveniently, been rewritten to highlight men – often older and white men – rather than acknowledge the movement’s indebtedness to women. Aimee Semple McPherson, as mentioned previously, is often written out of the history of Pentecostalism in America because she was a woman of great prominence and impact. Marie Griffith, writing in the International Dictionary of Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements (2003), states simply that “The history of women’s roles in Pentecostal and Charismatic movements is complex and contradictory.” While Pentecostalism and especially its later expressions in the Charismatic Movement have appeared

far more open to women’s preaching and leadership than have more mainstream Protestant churches such as the Presbyterians or Episcopalians” it is still the case that “male Pentecostal leaders have just as often drastically narrowed the boundaries within which their female counterparts may speak and act in positions of authority, so that Pentecostalism has come to be perceived as far more conservative than mainlines Protestantism on gender issues (“Role of Women” 1203).

This “openness” would quickly become a target for fundamentalists who already took issue with the strange behavior of Pentecostals. And so, as they did with race, the Assemblies of God would comply in practice if not theology with the hollowing and restructuring prescribed by The Fundamentals. For Pentecostals, this herky-jerky two-step of progress and conservative reform creates the “complex and contradictory” history of gender within their various expressions and, rather than lightly gesture to social changes, the instability and vacillation of positions can be directly linked to the dual origins of Pentecostalism in America rooted in either Parham or Seymour, in racism and acceptance, in gender empowerment and repression, through to the doctrinal confusion over whether tongues are a known (recognized human language) or angelic (not recognized or ever spoken by humans except in the ecstatic religious experience) where these men also differed.

The Assemblies of God certainly exemplified this tension. While they ordained women to ministry at their founding in 1914, they also took issue with the popularity of Aimee Semple McPherson, who was ordained by the denomination as an evangelist in 1919. Thie eventually culminated in the denomination disavowing McPherson and writing her out of their history, even though she unquestionably elevated the denomination to a national stage. McPherson finally broke from the Assemblies in 1922 after a contentious behind-the-scenes debate about the “place” and “role” of women in ministry and, specifically, as the denomination questioned her legitimacy. That year, the official publication of the Assemblies of God, The Pentecostal Evangel, published an article titled “Is Mrs McPherson Pentecostal?” in which they claimed McPherson had compromised her teachings in order to secure mainstream respectability. During the 1920s, some 10,000 people attended Angelus Temple, her church in Echo Park, a suburb of Los Angeles, and church records show that some 40 million individuals visited the church during the first seven years of opening (1923-1930), most of them seeking food and shelter during the Great Depression which Angelus Temple provided through a strong network of communal interdependence. McPherson actively sought out Midwesterners who suffered from the collapse of industry, the Dustbowl famine, and the Spanish flu. She also built ministries for Japanese and German immigrants, welcoming them to Angelus Temple and America with a toothy smile and hot meal. The church, still popular in Los Angeles, was recognized by the National Register of Historic Places in 1991 both for McPherson’s contributions to American culture and for its consistency in providing shelter and food to those in need during the Depression.

Women like McPherson and many, many more who bore no resemblance to her in style, appearance, or theology contributed significantly to the appeal of Pentecostalism, even in denominations like the Church of God or Pentecostal Holiness, both of which forbade women from teaching or pastoring. Even now, women of the Pentecostal Holiness tradition are identified by their long hair and skirts in strict adherence to Paul’s teachings about the appearance of women in society and both denominations insist that women remain silent in church. Their dress and hair are expressions of submission to their husbands, specifically, and patriarchy, generally, in the same way Islam insists on women wearing headscarves and having a diminished role in society. The Assemblies of God does not share these beliefs or practices, at least not publicly.

It was women who founded and built the Assemblies of God church in Ferriday. The Sumrall women literally got on their hands and knees to pull weeds, cut grass, and prepare the plot of land where they would build the church. It was the women of the Swaggart, Gilley, and Lewis households who steered the lives of a new generation. In many ways, the Assemblies of God’s allowance of women in ministry provided an equality that would make it possible for Jimmy Swaggart to esteem his grandmother so highly, to refer to her continually throughout his ministry, over the radio, and throughout his books. The love he held for her endured throughout his life, which is why her own baptism in the Spirit fascinated young Jimmy. Her experiences were, in a sense, his own. They were the model that he wanted to follow.

Continued in Chapter 5

One thought on “Biography: Jimmy Swaggart, chapter 4”