After a dramatic salvation experience, the boy felt a call of God on his life. He was destined for the ministry just like Jerry Lee and Mickey were destined for music. Having given his life to Christ and having felt a call to ministry, or at least a sense of greater purpose than what he observed in the lives of his family and the people of Ferriday, Jimmy began to withdraw. He would spend hours alone reading the Bible and praying. When he could get away with it, he visited his grandmother Ada. When he couldn’t, he became quiet and withdrawn, more focused in school. He wanted something more and was starting to build a way out of his meager upbringing.

He wasn’t alone in this. His cousin Jerry Lee Lewis was on a very different trajectory. He began failing school and became known for skipping class, engaging in small criminal activity, and picking fights before his attention finally turned toward music. It was not the banjo-plucking of the Swaggarts or the sedated hymns of the church but the loud and rowdy sounds coming out of the houses and saloons at the edge of town where Blacks lived. Biographer J.D. Lewis, author of Unconquered: The Saga of Cousins Jerry Lee Lewis, Jimmy Swaggart, and Mickey Gilley (2012) frames Ferriday as “the perfect harmonic convergence of blues, gospel, and country. It was on the Chitlin Circuit.” Lewis would sneak into clubs just to admire the musicians and the sounds they brought with them to the stage. In an interview with Country Roads magazine promoting the book, he reminded readers that

Will Haynie owned a club there called Haynie’s Big House. He was black and grew up dirt poor, but he became successful. Jerry would sneak in the back and listen to the blues. Sometimes Jimmy would go, too. Haynie allowed them to come in but told them not to let their rich uncle [businessman Lee Calhoun] know or he’d get in trouble. Everybody played there – eighteen-year-old B. B. King, Irma Thomas, Bobby ‘Blue’ Bland. It was one of the few places in the South where they could play and also have a place to stay, because Haynie owned a hotel in the back. People would come from Monroe, Alexandria, Shreveport. It was one of the most important blues joints in the South.

Even late in life, an elderly Jerry Lee would perk up whenever he was asked his thoughts about the contributions of Black musicians. He would continually point out that black musicians had been overlooked in the story of rock n’ roll, boogie woogie, and country music. Rattling off a series of names – Trixie Smith, Muddy Waters, Lightnin’ Hopkins, B.B. King, Son House, Bessie Smith – Lewis would become an outspoken and indignant evangelist for black musicians who had been erased from the origins of “American” music.

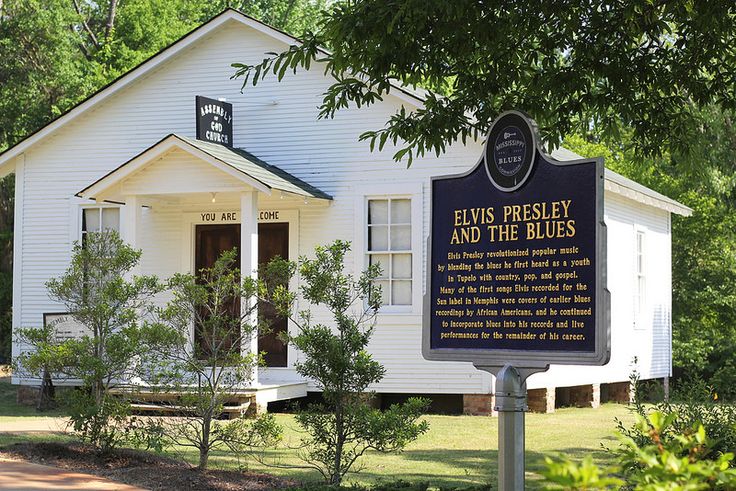

At the time, White musicians profited from “race music” without crediting Black songwriters, who often received scant if any royalties from theft of their work and sound. Big Mama Thorton received a miserly $500 for “Hound Dog,” the song that launched Elvis Presley’s career. White bands like the Rolling Stones commodified blues without acknowledging Black composers. Even when progress began to be made, Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, and Keith Richards would each claim, when the contributions of Blacks were beginning to be recognized, that they were present at Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s legendary “Didn’t It Rain?” performance at a Manchester train station in May of 1964. For them, it was proximity to a legend. For their careers, it was immediate profit based on proximity. Why didn’t more people know her name, Jerry Lee would ask, if all the great guitarists idolized her?

If left to rant long enough, he would become angry and take on a rolling stream-of-consciousness style that paralleled Jimmy’s crusades. Eyes wide, chin jutting, fingers pointing, Jerry Lee would preach about racism and discrimination, about the prophetic sounds in guitars, pianos, washboards, and voices, his own positively crackling. It wasn’t accidental, or infrequent. It was intentional. It was sinful, the way racism became embedded in the success of his contemporaries, catalogs sung by people who didn’t know their lineage. It’s no secret that Elvis covered blues songs from juke joint and Chitlin’ Circuit artists like Jerry Lee. According to legend, Sun Records founder Sam Phillips sought “a White man who had the Negro sound” when he discovered Elvis. Guided by “Colonel” Tom Parker and goaded by Phillips, Elvis would make millions. Along with Big Mama Thorton’s “Hound Dog,” Elvis would go on to claim Fats Domino’s “Ain’t That a Shame,” Big Joe Turner’s “Shake, Rattle, and Roll,” Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup’s “That’s Alright,” and Otis Blackwell’s “Don’t Be Cruel” and “All Shook Up.” Blues guitarist Big Bill Broonzy, who Eric Clapton, John Lennon, and Paul McCartney would name as an inspiration, would spend the last decade of his life as an indigent janitor. In the midst of so many seemingly overnight successes by White musicians indebted to Black artists, Jerry Lee would alienate himself. He kept talking about the pillaging taking place in rock n’ roll, the sin of it, the damnation and wrath of God that they were incurring. John Hagney, writing for Inlander, recalls that

Elvis knew it. “The colored folks been singing and playing it just like I’m doing. I got it from them,” he said in a 1957 Jet magazine interview. “People seem to think I started this business. But rock ‘n’ roll was here a long time before I came along. Nobody can sing that kind of music like colored people. I can’t sing like Fats Domino.”

When Elvis met the closeted, gender-fluid Little Richard in 1956, and they recorded together at Sun, Elvis emulated some of Little Richard’s mojo. Elvis’ pelvis wouldn’t exist without Richard.

Elvis did not birth rock ‘n’ roll. There was Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry. Elvis was not the only White artist to popularize the genre with White audiences. There were also Buddy Holly and Bill Haley. Unlike these other four “founders” of rock ‘n’ roll, Elvis was an uber-celebrity, one manufactured and crushed by the star-making machinery. Like Marilyn Monroe, the untenable dissonance between Elvis’ public persona and his private pathos are American tragedies.

Jerry Lee was not the only one witnessing the sin of rock n’ roll, railing against it in the morning hours and profiting from it at night. Swaggart’s early career in ministry was naming the wickedness that he saw every time he met with his cousin. Jerry Lee would often feed Swaggart stories, would fill in details, in an attempt to expose what was happening. It would bond them together, though they would deny it and take pains to differentiate themselves from one another. This discomfort, in many ways, is the heart of Pentecostalism.

James Brown grew up Pentecostal. Elvis Presley attended the Memphis First Assembly of God. Johnny Cash claimed one of his earliest memories was attending a Pentecostal church in Dyness, Arkansas. It left a mark on him. Bob Dylan, during his Christian phase at least (1979-1981), briefly attended a spirit-filled Bible school in Dallas, Christ for the Nations Institute. Ian Bell, in his biography of Dylan, Once Upon a Time: The Lives of Bob Dylan (2012), recounts that though there had been some religious and biblical imagery in Dylan’s lyrics during the Sixties and early to mid-Seventies, it was in 1978 that the artist “found God” in a Tucson hotel room. Dylan said that he sensed “a presence in the room that couldn’t have been anybody but Jesus”, and even felt a hand placed upon him. “It was a physical thing. I felt it. I felt it all over me. I felt my whole body tremble. The glory of the Lord knocked me down and picked me up.”

Writing for History Today, writer Randall Stephens explains that one of the most open secrets of rock n’ roll is the number of artists who have Pentecostal backgrounds, families, and faith.

In the summer of 1985, Swaggart was on the road, conducting one of his mass revival crusades in New Haven, Connecticut. Before the cameras and the glare of stage lights he paced back and forth, waving his arms like he was fending off a swarm of bees. He raised his Bible high above his head. He shouted at his audience about the moral degeneracy that dragged reprobates through the gates of hell. At one performance, he took aim at ‘the devil’s music’: rock and roll.

How had Christians made peace with this vile, hideous music, he asked with urgency in his voice, drawing out words like ‘pul-pit’ and ‘bye-bull’. The issue was a personal one for him, he confided, pausing for emphasis and lowering his voice before lunging at the crowd, finger pointed upward to drive home his jeremiad.

‘My family started rock and roll!’ he exclaimed in front of the silent assembly of thousands. ‘I don’t say that with any glee! I don’t say it with any pomp or pride! I say it with shame and sadness, because I’ve seen the death and the destruction. I’ve seen the unmitigated misery and the pain. I’ve seen it!’…

Pentecostalism – the fast-growing apocalyptic religion of spiritual abundance, speaking in tongues, healing and musical innovation – inspired many first generation rock and rollers. Jerry Lee Lewis, Swaggart’s cousin, along with Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Little Richard, B.B. King and others were all raised in or regularly attended Pentecostal services in their formative youth. Rock and roll – the soundtrack of rebellion and the music of side-burned delinquents and teenage consumers – owed a surprising debt to Holy Ghost religion. It is true that Pentecostalism formed just one of the tributaries that fed the raging river of rock and roll, but the importance of the spirit-filled faith to the new hybrid genre was significant.

Swaggart, Lewis, Cash, all of the big names in country and rock during the first half of the Twentieth Century are unanimous in expressing the heritage of their sound can be traced to Gospel music, to the sounds of the church. Even harder rock, like the sounds of the Eighties and Nineties, notes a fascination with the sounds of revival. Instead of just seeing this indebtedness as something in the past, Billy Corgan of the Smashing Pumpkins says he thinks the future of rock n’ roll is returning to its roots. In a 2013 interview with CNN, he claimed that the future of rock will be God.

I think there’s a big difference between popular music and influential music. Influential music has been hijacked… I once did a big American magazine feature called ‘The Future of Rock’ (and) my answer was God. They say, ‘Social security is the third rail of politics in America,’ well God is the third rail in rock and roll. You’re not supposed to talk about God. Even though most of the world believes in God, it’s sort of like, ‘Don’t go there.’ I think God is the great unexplored territory in rock and roll music… I don’t think suffering is good for business. Crazy is good for business.

Crazy was something the Swaggarts, Gilleys, and Lewises of Ferriday had in abundance. At the periphery, their cousin Mickey Gilley would also, in his own way, try to replicate the sounds of their childhood, at least initially. Yet each of the cousins remained tethered to the grandmother who raised them on stories of God.

In many ways, Jerry Lee and Jimmy were mirrors of one another, sides of the same equation. One can almost see their childhood being taken away from them, the way they would cling to their mothers, aunts, and grandmothers late into adulthood.

Jimmy gravitated toward his grandmother. She raised the boys on stories from the Bible and the hymns of the church. Jimmy read voraciously, the Bible specifically, transfixed by the legends of David slaying Goliath, Jesus healing the sick, of Abraham searching for a place whose builder and maker was God. Of the Holy Spirit and the miracles of the Church. Of David and Solomon, tempted by women. Of Jacob, who wrestled with God. Jerry Lee became the worst expectation of the adults around him. Loud. Profane. Bad at school, maybe stupid. Incompetent. Violent. A thief. Weak to his core. Susceptible to the thrall of the Devil with his diabolical promises of fame, women, alcohol, and money.

As children, it was Jimmy who would find Jerry Lee in the schoolyard, weeping and inconsolable that he had failed a grade in school. Jimmy pulled him with him back into the classroom and convinced the teacher to pass Jerry Lee anyway. Even then, Swaggart had a way of convincing people to do what he wanted. To believe, even when the facts were spelled out in front of them. To do the right thing. To see the good in people, even someone like “The Killer.” To believe that the impossible was not only possible but reasonable. It was a quality he learned from his grandmother Ada. Stephens continues.

Growing up in the Assemblies of God church, Jerry Lee Lewis and Jimmy Lee Swaggart were close. In fact, they were like brothers. They bonded over music and their shared Pentecostal experience. What they both lacked in formal education, they more than made up for in stage presence, style and charisma.

Jerry Lee’s aunt and Jimmy Lee’s grandmother, Ada, liked to tell family, friends, and anyone who would listen about the Holy Ghost baptism she experienced at a camp meeting in Snake Ridge, Louisiana. ‘You’ve got to get it’ she implored. ‘You’ve got to have it. You really don’t know the Lord like you should until you receive it.’ When the power of the almighty struck her, she said, ‘the presence of God became so real’. Suddenly ‘it seemed as if I had been struck by a bolt of lightning. Lying flat on my back, I raised my hands to praise the Lord. No English came out. Only unknown tongues.’

When Pope Leo XIII invoked the Spirit of God on January 1, 1901, by singing the hymn “Veni Creator Spiritus” (Come Holy Spirit, Creator Blest) to dedicate the twentieth century to the Holy Spirit, little did he know what was happening among the small group of students of Charles Parham in Topeka, Kansas. While many historians focus on the role of Parham and William J. Seymour in the outpouring of God’s Spirit through Pentecostalism, Agnes Ozman is often overlooked. Parham had already taken notice of believers speaking in tongues in his journeys.

For several years, Parham had been reading about an old phenomenon, glossolalia – speaking in tongues. Considered by Christians to be evidence of blessing by the Holy Ghost, or the Holy Spirit, this intensely emotional experience of ecstatic, unintelligible speech had a long tradition in Europe, especially in France and England. But its Christian tradition was sporadic; it had been discredited as Satanic for at least 900 years by the Catholic church. Psychologically, it is often connected with powerlessness, surfacing historically in times of severe religious persecution or decline, or economic privation. It is egocentric, meaningful only to the utterer, though it requires a listener. It was seen occasionally in the U.S., but was considered something only fringe groups did (Anne Rowe Seaman, Swaggart, 29-30).

It was to women that the gift of the Spirit would take hold; it was a woman who received the gift of the “baptism in the Holy Spirit” in the new century. Similarly, while the early chapters of the book of Acts in the New Testament focus on Jesus appearing to the Apostles and to Peter specifically, the Gospels are very defined in showing that Jesus met with women immediately after his resurrection. Women, in the history of the Church, have often been forgotten, displaced, silenced, or burned at the stake.

Ada was a strange one alright, even before she began speaking in tongues. She was the fourth of eleven children born to a loveless, abusive marriage. Circumstance made her strong-willed out of a need to survive. Growing up in Snake Ridge, Louisiana, she learned to plant cotton, beans, beets, corn, and rye with her siblings while their father would shout and yell as he passed the day away drinking. She learned to do what was necessary to avoid freezes and floods that could destroy, the plague of pests that could consume. She also learned to avoid drunkards like her father. She met her equal in Willie Henry, “W.H.”, at the age of 21; he was everything her father wasn’t. Strong, tall, quiet, steady, born to farming and hard work. Like her. They married in 1914, a few weeks before the Assemblies of God would form in Hot Springs.

By the time she married W.H., the land was changing. Farmland was richer elsewhere, new timber and government industries were popping up in Monroe, Shreveport, Ruston, and further away in Jackson, Mississippi. In 1924, one of her sisters left for Ferriday, 40 miles south. Then another sister. A brother. In 1930, Ada and W.H. had two teenagers, Arilla and Willie Leon or “Sun” who liked to play the fiddle. When they moved to Ferriday, it was only a railroad stop in Concordia Parish. Before that, it had been home to the 4,000-acre Helena Plantation of Helen Smith when she married William Ferriday in 1827; the family would leave in 1894 and with the advance of the railroad, a town came into existence. Lots were staked out and sold in 1903-04, and the town was incorporated in 1906, the same year a one-room school house was built. Helena Plantation was converted for use as a terminal and workshop for the railways.

In 1927, a levee along the Mississippi River burst near Ferriday. It was one of 145 damaged, overrun, or destroyed by the Great Mississippi Flood, the most destructive in U.S. history. Some 27,000 square miles underwater in depths of up to 30 feet in some places. President Hoover came with the Red Cross to examine the damage. More than 200,000 African Americans were displaced from their homes along the Lower Mississippi River and had to live for lengthy periods in relief camps. Then-Secretary of Commerce Hoover wept as he helplessly watched from high ground as a black family atop their cabin were carried down the river, presumably to death or displacement. Photographs of his attention to the region helped bolster his popularity and win the Presidency a few years later, but more famously, the scene would be immortalized by musician and composer Randy Newman in “Louisiana 1927”. Newman would lament the “six feet of water in the streets of Evangeline” and eulogize the land and all that had happened since “the winds have changed.” Many joined the Great Migration from the South to the industrial cities of the North and the Midwest; migrants preferred to move, rather than return to rural agricultural labor with unworkable land. Crops were ruined. Schools were let out and a few children sent away. The land would need time and patience to recover, but something had to be done. Nothing was. Those who remained eventually settled, recognizing they would be forgotten once again, their bodies perhaps the soil for another generation.

Ferriday became known as an alcohol town, populated by moonshiners, card players, thieves, and the desperate. It is probably kinder to recognize it as a border town to Mississippi, a few hours from Arkansas or New Orleans as you pleased. Streets and establishments were scene to fights, stabbings, and killings. This was partially due to the open gambling, but free-flowing bootleg whiskey was also a factor. The only doctor in for miles built a home across from the local hospital, establishing a monopoly over repairing the violence. The local gambling industry expanded during the 1920’s, when slot machines made an appearance. They could be found in almost every storefront. Prostitution thrived. Rosie Hester, ran several of the larger and better-known houses of prostitution, one of which was allegedly where Jimmy would be taken by his father, Sun, to make a man of him and make him forget all the foolishness he was getting from Sun’s mom, Ada

At that time, Ferriday was still very much a frontier-type town. The sidewalks were made of raised wooden planks, and cows and horses roamed freely through the unpaved streets. Eventually, it was tamed by new arrivals desiring a more stable life, and a more desirable environment to raise children. Businesses and churches sprang up, and a thriving timber industry began to develop. A cotton compress and storage warehouses, constructed in 1926, still stand. Another burst of growth occurred in the 1940’s with the discovery of oil. But the population of Ferriday has never, not even then during its heyday, exceeded 5,000. On maps, it is a tiny partition. In the car, a driver could be forgiven for not even noticing they had passed through the town. In daily life, bad water, inadequate garbage disposal, corruption, and poverty remain the only constant. The hospital, still in operation, only has 23 beds. The farmland was rich, fertilized by livestock and wildlife abundant in the woodlands and forests of North Louisiana and Southern Arkansas, the rivers, swamps, and bayous teeming with fish. In the coming decades, profits were also made by selling azaleas, magnolias, jasmine, and peaches. The people were poor, but there was predictability in subsistence. Cotton and cypress wood are, even now, abundant in Concordia Parish with its fertile land and hardwood forests though the state threatens to encroach on all of this with each new roadway to lure big businesses eager to strip these resources from people whose families have endured for several generations.

When the waters of the 1927 flood abated, bonds were issues to rebuild the levees and redirect the river where necessary. A levee project or a bridge, even a road, could employ and feed a hundred families for months or even, given Louisiana’s penchant for corruption when it came to government projects, years. Jimmy’s grandfather, W.H. Swaggart, was employed in this way, as were Mickey Gilley’s father and other members of the expanding family. W.H. knew how to trap and hunt, storing enough kill to get the family through winter after the move to Ferriday. He was a hard worker at the sawmill, the paper mill, during the annual pecan harvest, hired on during the cotton season. He even farmed on shares, corn and cotton primarily. His most lucrative work was not on the surrounding farms or in the factories. It was bootleg whiskey.

Ada was a drinker when she met W.H. but she saw the toll it was taking on him and their family. Prohibition was the law of the land after the 18th Amendment was passed in 1917. Temperance had already been popular before that, particularly among women who experienced the violence of men like W.H. After they had kids, Ada sobered up. She began attending church. W.H. had been a hard worker, but there were also long stretches where he would be jailed.

Arilla, Jimmy’s aunt, said that there were times when she and her brother Sun, Jimmy’s father, only saw their father behind bars. He would spend months at a time in the parish jail and “That’s why we stayed out of trouble. My father sold whiskey all my life and he drank it all my life.” He would work hard to make up for it the rest of the year. There was nothing steady, nothing reliable because no one could count on his faithfulness. Not even Ada. Among his growing list of faults, W.H. also visited caroused with women, and frequented homes where husbands were absent. It was one of the reasons Sun could be hard at times with Jimmy, too much of a disciplinarian with the boy. He knew temptation crouched at the door. In his father’s absence, Sun had to become responsible for himself, his sister, and his mother whose church attendance and unstable marriage caused him to question her mental health.

Roads remained unpaved in Ferriday until the 1940s, when construction began as part of the Public Works Administration of President Roosevelt. The Swaggarts and Gilleys picked up work where they could, including Sun. When he met Minnie Bell Herron, she was 13 to his 17. Next to the youngest of seven children, responsibility fell to Minnie Bell early on as it had for Sun. Though a child herself, she cooked, did laundry, and tended the house for her parents, worked their garden, worked the fields like Sun, and still managed to go to school. Sun was struck by her playful innocence, despite it all. He was, more likely, enamored with her smile and Cupid’s Bow lips. He had taught himself to fiddle and Minnie Bell knew how to play guitar, she sang with a clear contralto. It felt like a match. Unlike the other boys vying for her attention, including his uncle Robert Jay Lewis, Sun wanted to do it right. One afternoon, by then knowing her schedule, he continued working the field when Minnie Bell went inside for coffee and a bit of rest. When she came back out, Sun had finished the work for her. He wasn’t afraid of work and he refused to become like his father. Sun wanted to become a lawyer, like Governor Huey Long. He told Minnie Bell that he had wanted to be a lawyer since he was ten, about the time that W.H. began his extended stretches in jail. He also began training as a light heavyweight boxer. Tall, with auburn hair and intense blue eyes, a husky voice whether singing or talking, he had his choice of girls but gravitated to the tempestuous Minnie Bell, whose anger and quarrelous nature felt familiar.

That they were related by marriage may have been overlooked except that the family tree was intertwining. Sun was already his own uncle. His maternal grandfather, sharecropper William Herron, father to Minnie Bell. Their children would technically be first and second cousins. Niece and nephew to their parents. They even had the same birthday, February 15th, two years apart. They understood one another in deep ways that caused them to overlook one another’s faults at times, especially Minnie Bell’s temper. Even with all of this, Sun and Minnie Bell married on February 13th, 1934, in the midst of the Great Depression, determined to carry each other through at the young age of 19 and 17 respectively.

The following year, on March 14, 1935, their first child was born. Jimmy Lee Swaggart, Jimmy because Minnie Bell liked the name and Lee after their uncle Lee Calhoun who was the only one in the family with enough sense to bribe the police and convince them to look the other way when he opened a new distillery for his moonshine. Prohibition had been overturned in 1933 but with its legalization came cost prohibitive taxes, receipts and paperwork. Moonshiners and bootleggers like the Swaggarts, Calhouns, and Lewises sneered at government interference and avoided revenuers as much as possible. There was more money to be made in the old method of direct supply and demand entrepreneurship. Calhoun had the sense to buy up cheap housing in the Black section of Ferriday, “Bucktown”, and rent it back to them. He would hire tenants to work the fields, using land as the front of his enterprise.

Six months later in September, Jerry Lee Lewis was born. Like W.H., he spent time in jail for running liquor. With so much uncertainty and instability across the family, Ada became a praying woman. She urged the women of the family to come to church with her. This was why W.H. and, in turn, Sun scoffed at her. The women of the expanding family sure seemed to appreciate it when their “sinner” husbands, brothers, cousins, and uncles found ways – albeit illegal -to help them survive. It was the jailbirds and scofflaws who were holding the family together, not the God who flooded the land and sent the drought, who lined the pockets of bankers but not people who worked the land.

It was into all of this that Jimmy was born and raised. The more Ada tried to preach to Sun and tell him to turn his life over to God, the more Jimmy’s father warned the boy not to visit her. The world was hard and Jimmy, like all of the other men in the family, would have a hard row to hoe if he was weak like the women. Once Ada began listening to that lightheaded radio evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson out in Los Angeles – a woman preacher, can you imagine? – Sun became convinced his father had been right all along. Sun’s mother was crazy after all. Maybe there was something to his father’s infidelity. Sun wasn’t going to let Jimmy go sit and listen to Ada or that radio preacher when he needed to be out working the fields or going to school. The boy might catch whatever was wrong with Ada. He was soft as it was, always reading.

As Jimmy recounted hundreds of times,

There are children who sense at an early age the call of God in their lives, and who have a deep and abiding interest in God’s Word. As a child of eight, God saved me and baptized me in the mighty Holy Spirit. I recall the deep yearning and desire of my heart and life at that tender age.

I vividly remember, at eight years of age, going to my grandmother’s house time and time again. She was a true stalwart of Faith and taught me much of what I know about Faith today. She had been baptized in the Holy Spirit and a radical transformation resulted in her life. Glorious and wonderful changes produced a profound effect on our whole family.

I studied the Word of God with her and asked her over and over again to describe how God had filled her with the Holy Spirit. She repeated the experience time and again, but I would go right on asking her to go on telling it.

“Jimmy,” she would say, “there is nothing God cannot do. He’s a big God and He wants to do great things for you. Believe Him and stand on His promises.” She would smile and then as she pointed her finger at me: “God can do anything.”

She reminded me that God’s Hand was upon me, and she would then state without question that I would preach to thousands. Later on, after I began preaching, I found this prophecy hard to believe despite the fact that I knew God could do great things. She never failed to encourage me, though.

“Jimmy,” she would say, “you will see the sick healed, blind eyes opened, and lame legs walk, and you are going to witness miracles while you see thousands saved.” As she spoke, her eyes would sparkle, and influenced by her Faith, I almost found myself believing that all this could happen in my life.

As I sat, time after time, listening to the account of her baptism in the Holy Spirit, it created a deep hunger in my heart for a personal relationship with the Holy Spirit. I wanted what my grandmother had. She would seat herself, and I would kneel down on the floor next to her chair with my eyes closed, listening. I could hardly stand the suspense of waiting for her to reach the part where God had come into her heart, had baptized her in the power of the Holy Spirit, and she had begun speaking in tongues.

As she recounted this, the Presence and power of the Spirit of God would move over her in a marvelous way, and she would raise her hands and start speaking in other tongues, praising God. It would literally flow all through me, causing me to tremble and shake under the power of God. I returned again and again to hear this story and to experience the Presence of God’s power. I felt His glory move in my heart at the same time it moved in hers. This repeated exposure to my grandmother’s experience affected me deeply. After God baptized me in the Holy Spirit (still at the age of eight), I found I had a deep and lasting love for the Word of God. I relished it and read the Word of God constantly throughout my eighth and ninth years. I meditated on it and shared Spiritual Truths with my parents. My dad encouraged me, asking me to explain obscure Scriptures. I was just a child, but after I would explain them as I understood them, he would consult with our pastor for his opinion. He supported my interpretations and convinced both me and my father that my revelations were indeed arrived at with the help of the Holy Spirit. I am convinced that God gave me insight into Scripture because I meditated on it, I dwelt in it, and I loved it. (The Holy Spirit from Genesis to Revelation, 96-98)

One thought on “Biography: Jimmy Swaggart, Chapter 3”