Continued from Chapter 2, part B

As Burgess explains, participants in the new Pentecostal movement were rejected by their home churches, parent organizations, and family members. For this reason, skepticism and outright animosity toward ecclesiastical organizations and rival denominations remain part of the Pentecostal experience. It has always rejected and been rejected by formal religious bodies. Still, the success of Pentecostalism has always been its outsider status, even among themselves. Differences expressed between the camps of Pentecostalism have often been cause for division, the pulling apart and restoration of their ideologies at the heart of their strength. Even then, they still cannot agree on an origin point. Most Pentecostals agree that Pentecostalism “began” in 1901 in Topeka, Kansas with Charles Fox Parham.

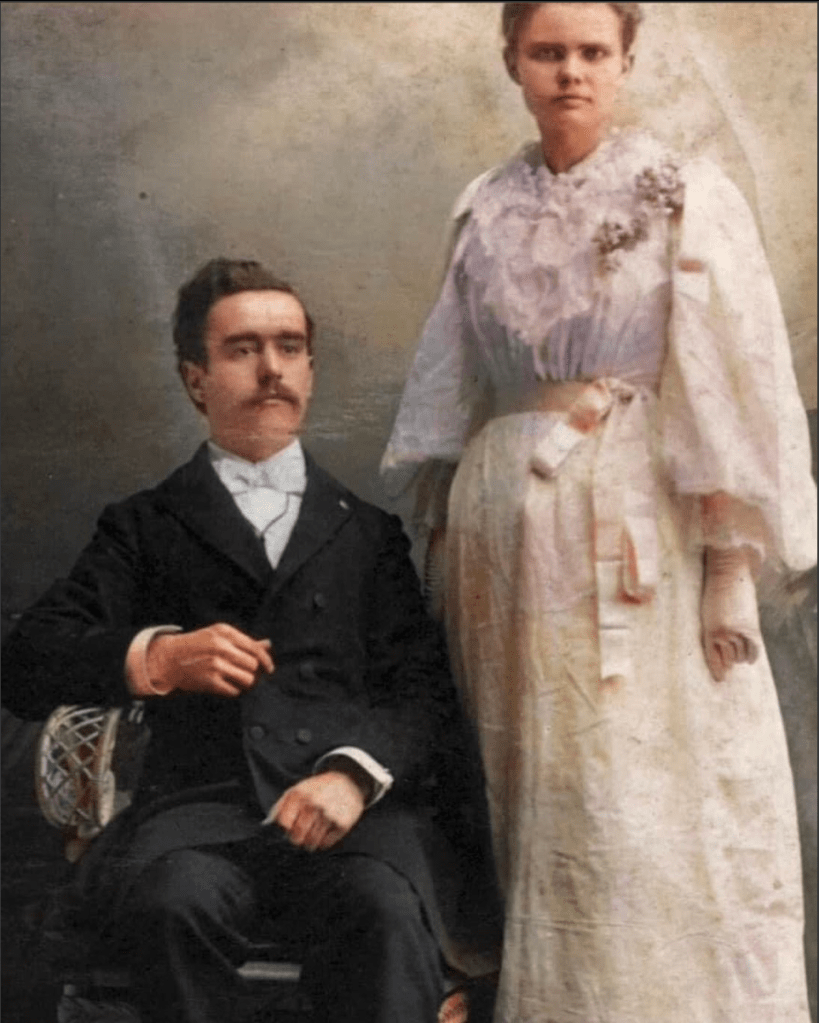

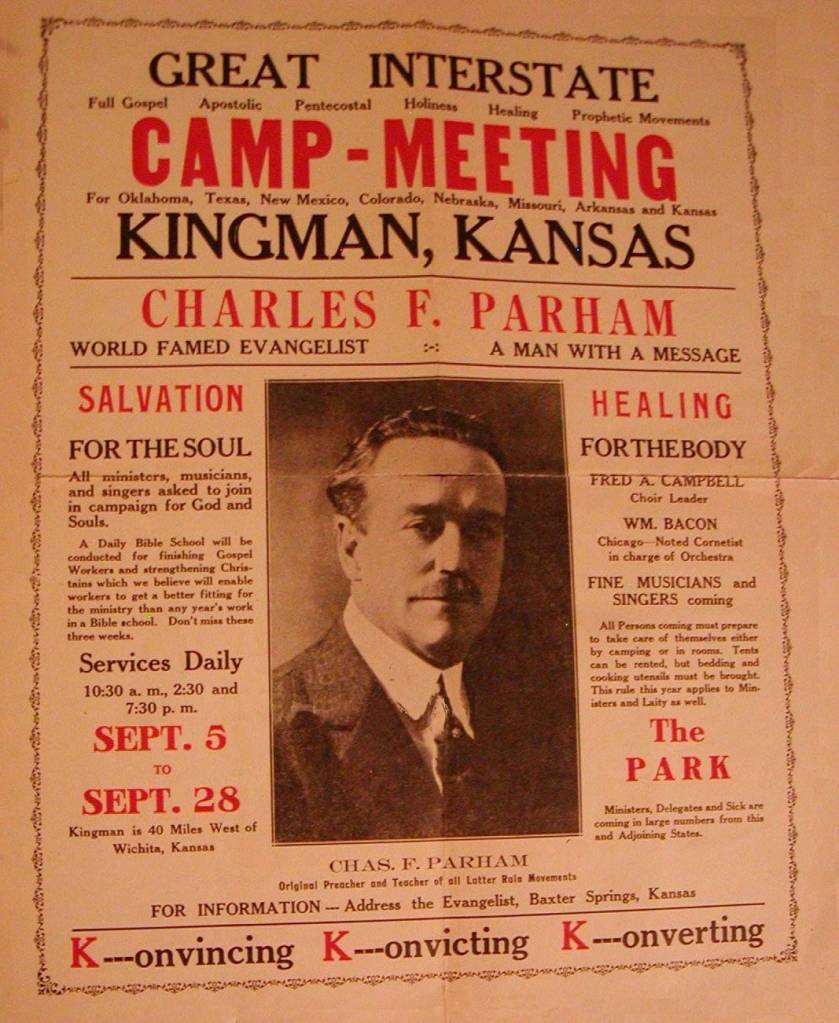

Parham began conducting his first religious services at the age of 15. In 1890, he enrolled at Southwestern College in Winfield, Kansas, a Methodist-affiliated school. He attended until 1893 when he came to believe education would prevent him from ministering effectively. He then worked in the Methodist Episcopal Church as a supply pastor, meaning that while he did menial work and met with congregants, he was never ordained. It was grunt work that would have left him frustrated and unfulfilled. Consequently, Parham left the Methodist church in 1895 because he disagreed with its hierarchy. He complained that Methodist preachers “were not left to preach by direct inspiration.” Rejecting denominations, he established his own itinerant evangelistic ministry, which preached the ideas of the Holiness movement. His plain-spoken folkish appeal was well received by the people of Kansas. Sometime after the birth of his son in September 1897, both Parham and the child fell ill. Attributing their subsequent recovery to divine intervention, Parham renounced all medical help and committed to preach divine healing and prayer for the sick. It only reinforced his unconventional views which continued to appeal to those who heard them. In 1898, Parham moved his headquarters to Topeka, Kansas, where he operated a mission and an office. It was a step forward as much as a “step of faith” to trust God for provision. In Topeka, he established the Bethel Healing Home, published the Apostolic Faith magazine, and opened the College, which all operated on a “faith” basis. He accepted donations, but did not solicit them.

According to his wife Sarah’s biography of him, published after his death in 1930, Parham was very aware of the time and context in which he lived. In Kansas, churches were built in “hard-scrabble circuits… [where] ministry seemed generally to be considered a great burden on society, which they don’t seem to be able to get rid of and which they are unwilling to support.” He took issue with the laziness of those in ministry, “of whom it is often said, they demand more salary than the school teacher and in return do the community little or no good; usually working about one-sixth of the time the teacher does.” Unlike the Methodists of his youth, Parham did not want to “sell” God or place demands upon people.

Having been a collecting steward and being thoroughly educated and trained in all the grafts and gambling schemes used to obtain money, until it seemed that it was absolutely necessary to put a poultice of oysters, strawberry short cake or ice-cream on the people’s stomachs to draw or burst open their purse strings. I was disgusted with the prospect (Sarah E. Parham, The Life of Charles F. Parham, 1930).

Parham refused to beg and manipulate. He felt he was obligated to spread the Gospel and, in turn, God was obligated to provide. To that end, Parham opened Bethel Bible College at Topeka in October 1900, operating the school on a “faith basis” of charging no tuition and trusting that God would provide the material and financial resources necessary. He invited “all ministers and Christians who were willing to forsake all, sell what they had, give it away, and enter the school for study and prayer.” About 40 people, including dependents, responded, according to Pentecostal historian Edith Blumhofer (Restoring the Faith: The Assemblies of God, Pentecostalism, and American Culture, 1993). At Bethel College, the only textbook was the Bible, the only teacher was the Holy Spirit, with Parham as the mouthpiece for God and only interpreter of scripture.

Born after the Second Awakening, Parham was raised on the legends of God and ministry. Like his predecessors, Parham longed for revival and new manifestations of the divine. “Deciding to know more fully the latest truths restored by the later day movements”, he took a sabbatical from his work at Topeka in 1900 and “visited various movements”, according to his wife Sarah E. Parham (The Life of Charles F. Parham, 1930). While he saw and looked at other teachings and models as he visited the other works, most of his time was spent at Shiloh, the ministry of Frank Sandford in Maine, and in an Ontario religious campaign of Sandford’s. From Parham’s later writings, it appears he incorporated some, but not all, of the ideas he observed into his view of Bible truths which he later taught at his Bible schools. In addition to having an impact on what he taught, it appears he picked up his Bible school model, and other approaches, from Sandford’s work.

Parham heard of at least one individual in Sandford’s work who spoke in tongues and had reprinted the incident in his paper, Apostolic Faith, as a “full baptism.” Whatever this meant, and what role his observance of other ministries together with the legends of the Second Awakening had on him and these religious communities, Parham came to the conclusion that there was more to a “full baptism” than others acknowledged at the time. By the end of 1900, Parham had begun teaching and leading his students at Bethel Bible School through his understanding that there had to be a further experience with God. He did not specifically point them to speaking in tongues or to seek miracles, personal healing, or any specific expression of God. Instead, he tried to remain open-minded himself and produce this same attitude in his students. It was a hands-off approach. At the end of December that year, he left his students for a few days, asking them to study the Bible to determine what evidence was present when the early church received the Holy Spirit.

The students had several days of prayer and worship, and held a New Year’s Eve watchnight service at Bethel on December 31, 1900. The next evening, January 1, 1901, they held a worship service when fellow student Agnes Ozman felt impressed to be prayed for to receive the fullness of the Holy Spirit. Almost immediately, she began to speak in what they referred to as “in tongues”, speaking in what was believed to be a known language.

God’s activity was brief though. Parham’s controversial beliefs, unconventional and at times aggressive (“enthusiastic”?) style made finding support for his school difficult. After all, he solicited no funds and his students claimed to speak other languages but were unable to translate it. The local press ridiculed Parham’s Bible school, calling it “the Tower of Babel”, and many of his former students called him a fake. By April 1901, Parham’s ministry dissolved. It was not until 1903 that his fortunes improved when he preached on Christ’s healing power at El Dorado Springs, Missouri, a popular health resort. Mary Arthur, wife of a prominent citizen of Galena, Kansas, claimed she had been healed under Parham’s ministry. She and her husband invited Parham to preach his message in Galena, which he did through the winter of 1903–1904 in a warehouse seating hundreds. In January, the Joplin, Missouri, News Herald reported that 1,000 had been healed and 800 had claimed conversion. In the small mining towns of southwest Missouri and southeastern Kansas, Parham developed a strong following that would form the backbone of his movement for the rest of his life.

Unlike other preachers with a holiness-oriented message, Parham encouraged his followers to dress stylishly so as to show the attractiveness of the Christian life. The attitude was unwelcome and, some felt, profane. Like the new religious movements of the Second Awakening, Parham had to decide to ignore his critics and break from the traditions of the past. He was even reluctant to call what he was doing “ministry” or the groups he spoke to “churches.” In 1904, he oversaw construction of a Pentecostal assembly in Keelville, Kansas. Other “apostolic faith assemblies” – by then, Parham refused to use the word “church” – were begun in the Galena area. Parham’s movement soon spread throughout Texas, Kansas, and Oklahoma. Meeting with tremendous success, in 1906 Parham began working on a number of fronts. In Houston, his ministry included opening another Bible school. While Parham clearly held racial views typical of the region, time, and context, he stopped short of denying admittance to people of color. Several African Americans were influenced heavily by Parham’s ministry in Houston, including William J. Seymour. Both Parham and Seymour preached to Houston’s African Americans, and Parham had planned to send Seymour out to preach to the black communities throughout Texas. In September he also ventured to Zion, IL, in an effort to win over the adherents of the discredited John Alexander Dowie, although he left for good after the municipal water tower collapsed and destroyed his preaching tent.

For about a year, Parham had a following of several hundred “Parhamites”, eventually led by John G. Lake. In 1906, Parham sent Lucy Farrow to Los Angeles, California, along with funds. Farrow was a black cook at the Houston school who had received “the Spirit’s Baptism” and felt “a burden for Los Angeles.” A few months later, Parham sent Seymour to join Farrow in the work in Los Angeles with more funds from the school. Seymour’s work in Los Angeles would eventually develop into the Azusa Street Revival, which is considered by many as the birthplace of the Pentecostal movement.

Parham, ultimately, proves a problematic figure to the history of Pentecostalism’s claims of “renewing” the Church. While Parham’s ministry was instrumental in bringing “the Pentecostal experience” into a new century, it should be recalled that he learned of the “gift of tongues” second-hand. He was not even present when Agnes Ozman received the gift of tongues or fullness of God’s Spirit.

While some have noted that Parham was the first to reach across racial lines to African Americans and Mexican Americans, including them in the young Pentecostal movement, this is not reflected in his sermons or the records of students who disavowed him. His alleged commitment to racial segregation begins to fall apart under examination; his attitude of superiority toward Farrow and Seymour come through in most accounts, as the clearest example. Historians Walter J. Hollenweger and Iain MacRobert claim in The Black Roots and White Racism of Early Pentecostalism in the USA (1988) that Parham was “a sympathizer of the Ku Klux Klan and therefore he excluded Seymour from his Bible classes. Seymour was only allowed to listen outside the classroom.” He may have extended a hand to Blacks and Mexicans, but he remained a segregationist until the end. J. Lee Grady, writing for Christianity Today in December of 1994, added that during the 1920s, Parham was also writing for a racist, Antisemitic periodical and continued to preach with the support of the Ku Klux Klan until near the end of his life (“Pentecostals Renounce Racism”).

Another blow to his influence in the young Pentecostal movement were allegations of sexual misconduct in the Fall of 1906. This was followed by his arrest in 1907 in San Antonio, Texas on a charge of “the commission of an unnatural offense,” along with a 22-year-old co-defendant, J.J. Jourdan. Parham repeatedly denied being a practicing homosexual, and the District Attorney dropped the case, but coverage was picked up by the press and local churches throughout Texas. Posters with a supposed confession by Parham of sodomy were distributed to towns where he was preaching, years after the case against him was dropped. The episode irreparably damaged and discredited both Parham and his religious movement. He was never able to recover from the stigma that had attached itself to his ministry and his influence waned.

In addition, there were allegations of financial irregularity and of doctrinal aberrations. In what was labeled a “Salem-like frenzy of insanity”, Parham’s followers killed three of their members in Zion, Illinois as a result of “brutal exorcisms.” Members of the group, who included John G Lake and Fred Bosworth, were forced to flee from Illinois, and scattered across America. (Barry Morton, “The Devil Who Heals: Fraud and Falsification in the Evangelical Career of John G. Lake, Missionary to South Africa” in African Historical Review 44(2):98-118, 2012).

In hindsight, it appears that Parham’s unpopularity in the Church met with opportunity when he deigned to speak to the Black congregations that welcomed Seymour but not necessarily Parham. The division between Parham and Seymour was one of teacher-student or master-servant, under the best of conditions. It is more likely that the separation came about once it became clear that Seymour’s ministry was ascending. If Parham saw himself as an apostle, he would not have accepted a rival and certainly not a Black man. As the focus of the movement moved from Parham to Seymour, Parham became resentful. His attacks on emerging leaders coupled with the allegations alienated him from much of the movement that he began. He became an embarrassment to a new movement which was trying to establish its credibility. His documented belief in British Israelism, an ideology maintaining that the Anglo-Saxon peoples were among the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, only compounds the matter further and has often led historians and biographers to consider him as a problematic figure, to say nothing of his gradual criticism of the Church. Parham was becoming increasingly detached from both his base and reality. If Pentecostalism was a revival of the early Church, Parham makes this impossible. His early criticisms crescendoed into a refusal to call his gathering a “church” service at all. That he would call these gatherings “apostolic”, a term laden with top-down authority with himself at the head (and not, say, Jesus Christ) makes a sympathetic reading of his later ministry a challenge. Shamed and no longer welcome with many of the congregations he had influenced, inspired, and helped found, he went off to search for Noah’s Ark and died in obscurity. Having claimed that he had been healed of rheumatic fever as a child, he began to experience health problems in 1927 likely brought on by a deteriorated heart. His trip to the Holy Land in 1928, a lifelong ambition, did not provide any evidence of the existence of Noah’s Ark. He died in Baxter Springs, Kansas in 1929.

Azusa Street Revival

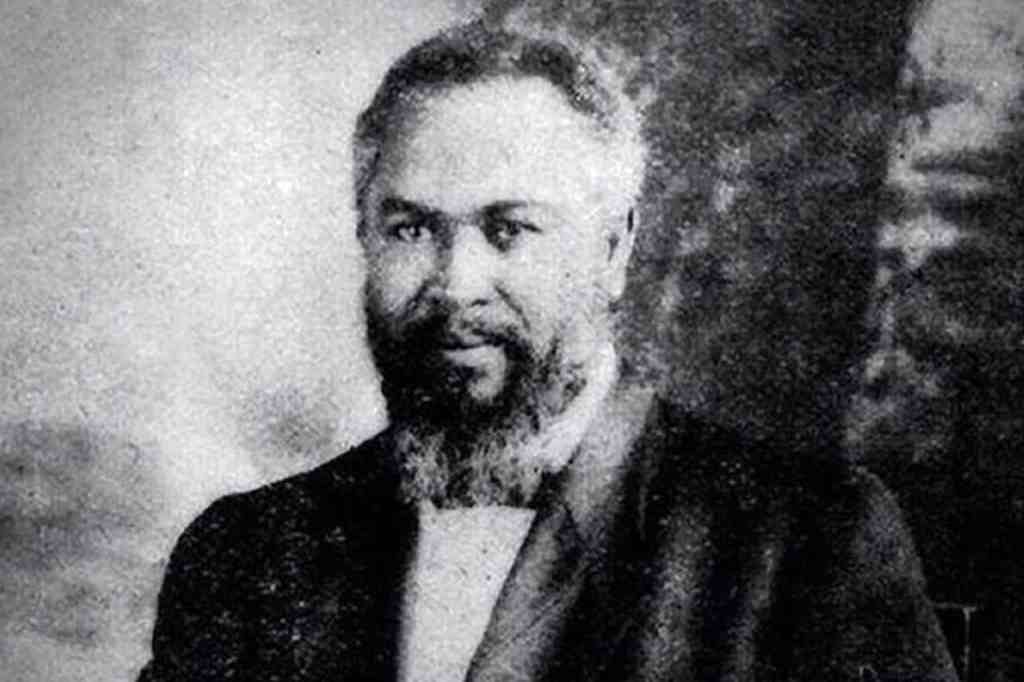

William Seymour was the second of eight children born to emancipated slaves in Louisiana. He was raised Catholic and, like Swaggart, grew up in extreme poverty in Louisiana. In 1891, when William was twenty-one, his father died. He became the primary provider for his family, growing subsistence crops with very limited income from other sources. The family was able to keep their property but lived at the poverty level. In 1895, Seymour decided to move north to Indianapolis, away from the persecution endured by southern blacks around the turn of the century. There, he attended the Simpson Chapel Methodist Episcopal Church and became a born-again Christian. There, Seymour was introduced to the Holiness movement through Daniel S. Warner’s “Evening Light Saints”, a group whose distinctive beliefs included non-sectarianism, faith healing, foot washing, the imminent Second Coming of Christ, and separation from the world in actions, beliefs, and lifestyle. This included not wearing jewelry or neckties. In 1900, as Parham’s ministry was gaining notoriety, Seymour returned to Louisiana. It seems from records of the time that he was beginning to reconsider the restrictive beliefs of the Evening Light Saints and the Holiness Movement, but remained curious about the workings of God and seems to have felt a call to ministry which time, circumstance, place, and race made difficult to fulfill.

In 1901, Seymour moved to Cincinnati, where he worked as a waiter and probably attended God’s Bible School and Training Home, a school founded by holiness preacher Martin Wells Knapp. At Knapp’s school, blacks and whites studied side by side. Knapp taught Premillennialism, that Jesus would return prior to a literal thousand years of peace. He also took seriously special revelation, or the will of God expressed through dreams and visions. While in Cincinnati, Seymour contracted smallpox. He was blinded in his left eye and would come to blame this disability on his initial reluctance to answer God’s call to the ministry.

Seymour moved to Houston in 1903. During the winter of 1904–1905, he was directed in a dream to move to Jackson, Mississippi, where he would receive “spiritual advice from a well-known colored clergyman.” He probably met Charles Price Jones and Charles Harrison Mason, founders of what would become the Church of God in Christ. It would not be his only encounter with the various founders and framers of Pentecostalism. He had already met Charles Parham and John G. Lake, who went on to found a healing ministry in South Africa.

Although speaking in tongues had occurred in isolated religious circles as early as 1897, Parham began to practice it in 1900 and made the doctrine central to his theological system, believing it to be a sign that a Christian had received the Baptism with the Holy Spirit. On January 1, 1901, Parham and some of his students were praying over Agnes Ozman when she began to speak in what was interpreted to be Chinese, a language Ozman never learned. Pentecostals identify Ozman as the first person in modern times to receive the gift of speaking in tongues as an answer to prayer for the baptism of the Holy Spirit. Parham also spoke in tongues and went on to open a Bible school in Houston as his base of operations in 1905.

In 1906, Lucy Farrow took a position with Parham’s “ministry” as nanny to his children. She wrote and asked Seymour to pastor the Holiness church she attended, believing in him thoroughly and his call to ministry with the African-Americans of Houston. With Farrow’s encouragement, Seymour joined Parham’s newly founded Bible school in Houston but under very specific conditions. Technically, Seymour’s attendance at Parham’s school violated Texas’ Jim Crow laws; with Parham’s permission, Seymour took a seat outside the classroom door. Inside churches (at least those with Black congregations), Parham and Seymour ministered together. At least with Parham “allowing” Seymour to preach to Blacks. Even God had to abide by the laws and customs of Texas.

During this time, Seymour continued praying that he would receive the baptism with the Holy Spirit. Though unsuccessful at the time, he remained committed to Parham’s teaching that speaking in tongues was evidence of God’s Spirit in the life of the believer. He rejected many of Parham’s other beliefs, however, like the annihilation of the wicked and the use of tongues in evangelism. Parham understood the gift of tongues to be xenoglossy, unlearned human languages to be used for evangelistic purposes. Seymour seems to have believed that tongues were an ecstatic utterance of praise or a prayer language to God, the sole audience. Presumably, Seymour also took issue with Parham’s other teachings about race. Whatever the proximity of their individual beliefs, and the concessions that had to be made for Seymour to remain part of the work Parham was building, their time together was brief. Within a month of studying under Parham, Seymour received an invitation to pastor a holiness mission in Los Angeles founded by Julia Hutchins, who intended to become a missionary to Liberia. Parham believed Seymour unqualified, ostensibly because he had not yet been baptized in the Holy Spirit. Seymour went to Los Angeles anyway.

Committed now to fulfilling the call of God on his life, Seymour initially considered his work in Los Angeles under Parham’s authority. He requested and received a license as a minister of Parham’s Apostolic Faith Movement, at least. However, Seymour soon broke with Parham over his harsh criticism of the emotional worship at Azusa Street and the intermingling of whites and blacks in the services. Given Seymour’s pattern of moving whenever racism was evident, it seems more likely that he left for Los Angeles for this reason. Lending more weight to this, Parham’s racism became evident and more widespread from this point forward. Parham criticized Seymour specifically and more broadly criticized desegregated churches, Black people, and Jews. The criticism he offered of the Azusa Street ministry for allowing intermingling of races only continues to reinforce the conclusion that Seymour had learned all he needed to from Parham and decided God was leading him in another direction. Mark Noll explains

///

In 1906 an abandoned Methodist church at 312 Azusa Street in the industrial section of Los Angeles became the cradle for this new movement. William J. Seymour (1870 – 1922), a mild-mannered black holiness preacher founded the Apostolic Faith Gospel Mission on Azusa Street, where a new emphasis on the work of the Holy Spirit rapidly became a local sensation that eventually gave birth to a worldwide phenomenon… [It] rapidly attracted attention from the secular media, including the Los Angeles Times. It was marked by fervent prayer, speaking in tongues, earnest new hymns… and healing of the sick. One of its most prominent features was the full participation of women in public activities. In an America that still took racial barriers for granted, Azusa Street was also remarkable for the striking way in which blacks and whites joined to participate in its nightly meetings. Soon the Azusa Street chapel became a mecca for thousands of visitors from around the world, who often went back to their homelands proclaiming the need for a special postconversion baptism of the Holy Spirit. These included Florence Crawford, founder of the Apostolic Faith movement in the northwestern United States; missionary T. B. Barratt, who is credited with the establishment of Pentecostalism in Scandinavia and northwestern Europe; William H. Durham of Chicago, early spokesman for Pentecostalism in the Midwest; and Eudorus N. Bell of Fort Worth, first chairman of the Assemblies of God. From a welter of new alliances, networks of periodicals, and circuits of preachers and faith-healers, the Assemblies of God, established in 1914, emerged as the largest Pentecostal denomination… Later observers have noted that Pentecostalism spread most rapidly among self-disciplined, often mobile folk of the middle and lower-middle classes. But an ardent desire for the unmediated experience of the Holy Spirit was a still more universal characteristic of those who became Pentecostals (A History of Christianity in the United States and Canada, 386-387).

The success of this strange new revival in the middle of the Third Great Awakening and to a large extent its defining expression made Swaggart’s claims of prophecy and fulness of God’s Spirit possible. After all, if the presence of God was identifiable in people of color, in women, and in those of non-American origin, it was plausible that God might also appear in the lives of children. Pentecostals contextualize their emergence in American Christianity as a fulfillment of the prophet Joel in the Bible, where God promises “afterward,” or at some much later point, “I will pour out my Spirit on all people. Your sons and daughters will prophesy, your old men will dream dreams, your young men will see visions.” To challenge Swaggart’s claims would be to challenge the word of God.

It would become a recurring theme of Swaggart’s life and ministry, the fixed point of his temper and the criticisms he would return on those who challenged him, his ministry, and the claims he made about God’s special revelation to him.

Shortly after receiving salvation, Jimmy became curious and eager for a second experience, something that would continue to provide excitement or at least affirmation. His father could be harsh at times, even after he and Minnie Bell were saved. Returning to Ferriday felt like an admission of failure, the entire journey to Texas together with the loss of baby Donnie. Jimmy was convinced of his own wickedness. His father told him as much regularly. But Jimmy wanted what his parents wanted, hope that this circumstance might change. He wanted the thrills and chills to continue coming, the Pentecostal experience of a “second blessing.”

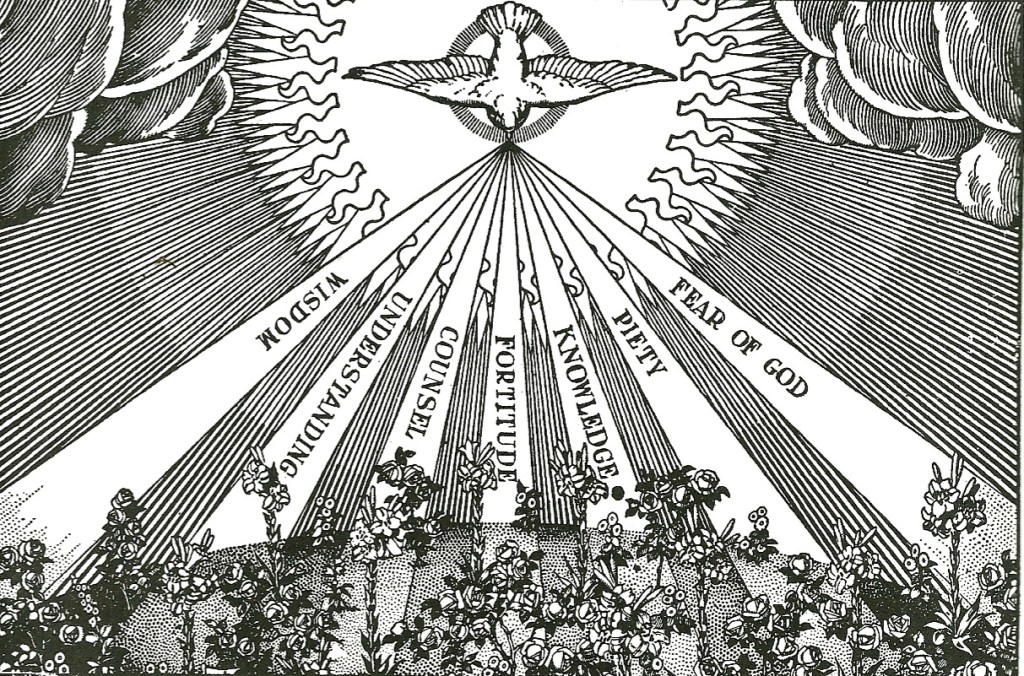

In Pentecostal theology, the presence of the Spirit of God in a believer’s life is not possible without salvation. With the filling of the Spirit comes a change of heart, even personality. According to scripture, the “fruits” or evidence of God’s Spirit in the Christian’s life are character traits like love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control. In some contemporary translations, qualities like mercy, generosity, modesty, chastity, charity, or temperance may be found. Explicitly named in Paul’s epistle to the Galatian church, implicit in religious communities, or sprinkled into pastoral sermons today, a change in one’s life is evidence of God’s activity in the life of the believer. The fruits of the Spirit are indiscriminate in this way, expected of all within the Christian community. Even children.

What is less uniform in the Christian understanding is what Paul means by the “gifts” of the Spirit, how they are applied, and a consensus on both their form and function. Since the start of Pentecostalism in 1901, a constant criticism of the movement has been its insistence on the presence, evidence, and gifts of the Spirit of God. Along with the character qualities of the “fruits” (evidence) of the Spirit are a series of gifts or giftings, the charismata applied by, for, with, and to the Spirit of God.

In most denominations, charismata are emphasized less, despite the fact that they are discussed more explicitly in scripture than the fruits/evidence of God’s Spirit. The fruits of the Spirit only receive a passing mention in Paul’s epistle to the Galatians yet the charismata appear throughout the book of Acts. The author of Acts takes pains to contextualize the miraculous circumstances and events of the early Church as a fulfillment of prophecies in the Hebrew Scriptures, like the one in Joel. The depictions of God’s Spirit among the people of God is not limited to Acts; Paul continually describes the presence of God’s Spirit in the New Testament, primarily in 1 Corinthians 12, 13 and 14, Romans 12, and Ephesians 4. John takes them as a matter of course in both the Gospels, evidence of Jesus’ divinity. He revisits the miraculous in his depiction of the apocalypse in Revelation. The “rock” of the Church, Peter, also touches on the spiritual gifts in his first epistle. Together, the major voices of the first generation of Christianity explain the following.

- Romans 12:6-8 names prophecy, serving, teaching, exhortation, giving, leadership, and mercy.

- 1 Corinthians 12:8-10 names word of wisdom, word of knowledge, faith, gifts of healings, miracles, prophecy, distinguishing between spirits, tongues, and interpretation of tongues.

- 1 Corinthians 12:28-30 names apostle, prophet, teacher, miracles, kinds of healings, helps, administration, and tongues.

- Ephesians 4:11 names apostle, prophet, evangelist, pastor, and teacher.

- 1 Peter names whoever speaks and whoever renders service.

While not specifically defined as spiritual gifts in the Bible, other abilities and capacities have been considered as spiritual gifts by some Christians. Some are found in the New Testament, such as:

- celibacy (1 Corinthians 7:7)

- hospitality (1 Peter 4:9–10)

- intercession (Romans 8:26–27)

- marriage (1 Corinthians 7:7)

- witnessing (Acts 1:8, 5:32, 26:22, 1 John 5:6)

Others are found in the Old Testament, such as:

- craftsmanship (such as the special abilities given to artisans who constructed the Tabernacle in Exodus 35:30–33)

- interpretation of dreams (e.g. Joseph and Daniel) in Genesis 43-50, Daniel 2

- composing spiritual music, poetry, and prose

In the records of the first four centuries of the Church, mystics would go on to claim that the Spirit of God was found in contemplative silence as well as loud worship. Which is to say that while Pentecostals have often taken a defensive posture, softening the edges of their beliefs to be accepted in civil discourse, having to explain themselves with theological terminology that does not come naturally, and restricting public expressions of their beliefs to avoid ridicule as pew jumpers, holy rollers, snake handlers, weirdos who “speak in tongues” perceived as gibberish, there is instead a very wide, broad acceptance of God that gets overlooked. Their claims are not strange, when taken together.

The “spiritual gifts” listed here seem to be broad examples of the human experience. Even if one were seeking to define and limit them, to itemize a list of anticipated expressions of the divine within the Israelite, Jewish, and Christian communities, what shines through is the diversity of God’s presence among the people of God. At one end of the spectrum is celibacy, marriage at the other. Silence and sound. Trusting one’s own experience, even if it doesn’t make sense at the time. Creative expressions through song, painting, architecture.

With such a wide variety of experiences, Pentecostals place emphasis on speaking in tongues as an initial evidence of God’s Spirit in the life of the believer, not because it is the most important but probably because it is the most recognizable and the one most attested to by scripture. Tongues (or glossolalia) seems to be the most commonly depicted in Acts and the epistles. Acts 19 emphasizes it as the initial evidence of being “baptized into the Spirit”, a second baptism in the Christian experience. In Ephesus, Paul challenges the salvation of a community of believers who were baptized by John the Baptist, Jesus’ cousin. He approaches the community by asking if they had “received the Holy Spirit” when they believed. They express confusion, replying that while they are convinced that they believe, they don’t know what he is talking about. Receiving the Holy Spirit? How does one receive the Spirit of God?

Paul explains in Acts 19:4 that John’s baptism was valuable, but only to cleanse the believer from sin. With the death and resurrection of Jesus, such baptisms were incomplete. Notably, Paul does not challenge their salvation or faithfulness. Instead, he explains that a second baptism was required now that Jesus had died and ascended to Heaven, one where believers who had been baptized from sin and cleansed would be baptized into something, a new life. Acts 19:6 explains that as soon as Paul began this second baptism “in the name of the Lord Jesus,” when he placed his hands upon them, “the Holy Spirit came upon them and they spoke in tongues and prophesied.”

It was this “second blessing” that Jimmy sought out after his salvation. He did not want to be a passive believer, even as a child. If he was going to do anything, it had to have purpose. He felt that while his salvation was meaningful, there was more to it than acceptance of a life filled with the drudgery of hard work, punctuated with singing and a weekly altar call to assure one’s salvation. There had to be something more.

Continued in Chapter 3

One thought on “Biography: Jimmy Swaggart, Chapter 2 (C)”