Despite their comparatively recent founding in 1914, the Assemblies of God have a long and rich theological tradition. They are the largest Pentecostal denomination in the world, claiming 86 million adherents worldwide. In America, they are the second largest; the Church of God in Christ claims 6.5 million members in the United States whereas the AoG claims 2.9 million members. When the Assemblies of God were founded, there was an effort to move the confederation of Baptists, Methodists, Pentecostals, and Church of God in Christ members toward a shared theology. It was always intended to bring prominence to the “role” and “place” of the Holy Spirit in the post-Calvinist experience.

Admittedly, many of the behaviors of Pentecostalism were offputting and inconsistent. Early Pentecostals were chronicled as “barking mad” for the strange barking sounds they sometimes made; a bark is a short, high-pitched, and abrupt vocalization that can change in frequency and repeat quickly. Some Pentecostals try to explain these sounds as glottal and guttural expressions, a pre or post-verbal expression by a human in spiritual ecstasy. Perhaps there is legitimacy to this. Humans can make sounds that are similar to barking when their laryngeal muscles spasm. Other Pentecostals were “holy rollers” when they collapsed to the floor and began to roll around. Here too, Pentecostals legitimize these behaviors as loss of muscle control, a “falling away” or “release” when one is “slain in the Spirit.” There were also “pew jumpers” and “runners” when believers, supposedly filled or full of the Spirit of God, would become overwhelmed with joy and begin to move ecstatically, if not erratically. Here too, these behaviors might be explained away. Perhaps, caught up in collective mania, an excess of adrenaline and elevated heart rate compels individuals to excessive movement, jerking, even leaping over pews. But there were also ecstatic, though still erratic, behaviors like snake handling and drinking poison as proof of God’s delivering power. These behaviors, often grouped together with glossolalia and claims to the miraculous by their Appalachian cousins, caused many Pentecostals to worry that their message of salvation and fullness would inhibit their migration into the mainline religions of America. After all, less than a century earlier, Mormons were beginning to make progress when their insistence on polygamy had shuttered their hopes of respectability in larger circles of influence.

The Great Awakening (1730 – 1755)

After the Revolutionary War, a new restlessness emerged. Americans were eager to test the limits of their freedom in the new democracy and were not limited to politics. It remains a false claim that America was founded as a Christian nation, though religion was unquestionably one of the things the Founders took into consideration and wanted to restrain. Themes from Puritanism like social policing, the murder of witches who practiced folk wisdom or other “false” religions, and hierarchies upon which a religious leader could rule were rejected. All people would be free to worship or refrain from worship as they saw fit. Though, it is obvious the ideal was difficult to embody. Thomas Jefferson, for example, took a knife to the Bible, specifically the Christian Scriptures, to remove passages where Jesus performed miracles. He was adamant that America should reject the Puritanical emphasis on supernaturalism for rational thought. However, Jefferson also held slaves and it was open knowledge that he had sex with many of the women under his benevolence. John Adams, the second President, adamantly and tirelessly insisted that people would be equal in the new nation being established. Yet he met his wife’s furious letters demanding that he “remember the women” and pleas to his Christian character with patronizing and condescending dismissal. In hindsight, it might appear that the Founders rejected the language of religion for a more rational political dominance, one that took the shape and form of similar oppression baptized not in the saving waters of Jesus Christ but in the timelessness of tradition. Still, the restless tendency did not diminish with the signing of declarations or the swearing-in of Presidents. It continued to swell, spilling over and taking shape in the fires of American religious experience. Puritan ideas added moral force to patriotic arguments and, if anything, the Founders likely wanted to restrain the American tendency to baptize evil. They were themselves well acquainted with the intoxicating thrall of power, Jefferson with a strong hand on his Monticello plantation, Adams with the stroke of a pen to his wife.

Few of the early leaders were above using religious traditions, specific biblical sanctions, “common sense”, or appeals to tradition to justify their political activity. Writing for the Eerdmans’ Handbook to Christianity in America (1983), historian Mark Noll points out that religious ideas “contributed to Revolutionary thought” and, despite the desire of the Founders to make a distinction between church and state, politics and religion in Early America “shared a pessimistic view of human nature. Puritans believed that natural depravity predisposed individuals to sin” while political parties of the time “held that political power brought out the worst in leaders.” Both politics and religious institutions “emphasized that freedom meant liberation from something. For Puritans it was freedom from sin” but for political parties, “it was freedom from political oppression.” The tension of colonists only continued to percolate, often spilling over into other domains of life at each incremental change in society, law, and governance under the “wicked” oppression of their “tyrant” King, into race and gender, into the growing division of class, in the taverns and roadways. The ideas of revitalizing the Church during the Reformation had given way to strict social constraints which, in turn, gave language to revolution for the religious and politically frustrated. With the same parentage and even raised together for such a sustained formative period, politics and religion have always been quite familiar with one another in America and have remained so until the present moment, despite the intentions of various thinkers. Noll writes of the confederation that had developed around the Revolutionary Period, looking at the growth of the Whig Party and Puritans.

Both also linked freedom and virtue. Puritans held that sinful behavior led to spiritual and other forms of tyranny; Whigs felt that tyrannical behavior grew from corruption and, in turn, nourished it. Finally, Puritans and Whigs both regarded history in similar terms. It was the struggle of evil against good, dark against light, whether for the Puritan (Antichrist versus Christ) or the Whig (tyranny versus freedom). This similarity in form between Whig political ideas and the traditional theology of some Americans made it easier for many to blur the distinction between a political struggle for rights and a spiritual conflict for the kingdom. (Noll et. al., 134 – 135).

Out of this struggle emerged the Great Awakening, the first of many such populist religious movements. Religious hierarchy kept the masses silent in their churches through a combination of classist elitism, literacy, and a conference of power. In a letter to Governor Jonathan Belcher, New England Puritan preacher Samuel Willard claimed that “The Alwise God hath ordained orders of Superiority and Inferiority among men and requires an honor to be paid accordingly” (Petition to Governor Belcher, 1747).

Belcher was a beneficiary of the class system in New England; he was a merchant, politician, and slave trader from colonial Massachusetts who served as both governor of Massachusetts Bay and governor of New Hampshire from 1730 to 1741. He would later become the governor of New Jersey from 1747 to 1757. To consolidate family wealth, Governor Belcher insisted that the son of his first marriage be allowed to marry the daughter of his second marriage, a not uncommon practice at the time. In religious services, even in religious matters outside the Church, those of a lower class were told to be civil and not rise above their station. But commoners could not help but notice the condescension and haughtiness of those who claimed to be superior by the will of God, the hypocrisy of their claims inside of a church, and their behavior out of it. That Belcher’s behavior would be sanctified by Willard and, in turn, that the Church would be given power by the wealthy in a mutually beneficial corruption only compounded the matter. Yet the less educated – women, people of color, and the poor – were indoctrinated to hold their silence out of deference to their divinely instituted superiors. The Great Awakening was about far more than seeking salvation, then. It was an extension of the Reformation, a refusal of the evil carried over from Europe with pernicious oversight of the Papacy on the one hand and oppressive, often capricious rule by tyrants in the name of God on the other.

In another volume, A History of Christianity in the United States and Canada (1992), Noll elaborates beyond the Whigs and Puritans. He notes that those who esteemed a republic

And the evangelical heirs of the Puritans also shared a common view of history. Both regarded the record of the past as a cosmic struggle between good and evil. To American Christians, good and evil were represented by Christ and anti-Christ; to republicans, by liberty and tyranny. Both republicans and Puritans longed for a new age in which righteousness and freedom would flourish. Both hoped that the Revolution would play a role in bringing such a golden age to pass. (118).

The Church was not exclusively the home for corruption, however. A great number of published sermons, journals, and letters evidence a growing revolutionary spirit encouraging a defense of political liberty in New England among Presbyterians and Congregationalists as well as in the South among Baptists and other smaller denominations.

Even some clergymen of the Church of England, contradicting the official allegiance of their denomination, denounced the grasp of Parliament… In general, the services of believers to the patriot cause were great and multiform. Ministers preached rousing sermons to militia bands as they met for training or embarked for the field. Many ministers servced as chaplains. Ministers joined Christian laymen on the informal commitees of correspondence that preceded the formation of new state governments. Other ministers served gladly as traveling agents of the new governments who wanted them to win over settlers in outlying areas to the support of the patriot cause. Throughout the conflict, common soldiers were urged to their duty by the repeated assertion that Britain was violating divine standards. (ibid).

To a great extent, the outdoor revivals of the Great Awakening which preceded the American Revolution fueled the attitudes and made such sermons, delivered from seats of authority, possible. Historians mark the Great Awakening as taking place between 1730 and 1755, the tail end just one generation away from the Revolution. But if the message of change and salvation were familiar to colonial ears, it was because of “the electrifying manner of its presentation and the open-air setting” of itinerant ministers like George Whitefield. Historian Harry Stout writes that the form of communication itself was the means by which Awakening and Revolution could even be conceived.

Considered as a social event, the issues of the revivals hung particularly on questions of free speech related to the novel practice of clerical itinerancy, lay exhorting, and lay ordination. All of these activities involved a new role of leadership and assertion for common people who hitherto had content to sit under the ministry of local clergymen supported by the public taxes. The new wave of popular speakers born in the revivals issues not only in spiritual ‘enthusiasm,’ but in a social enthusiasm as well. The Great Awakening transformed traditional conceptions of public address and social authority and paced the way for emerging democratic ideals which would triumph in the American Revolution. The innovations in organization and rhetoric that Whitefield and his allies first perfected would experience their own ‘new birth’; they would become familiar and popular institutions during the creation of the American Republic a generation later.

To modern observers accustomed to two centuries of religious revival, campfire meetings, lay testimonials and preaching, and the separation of church and state, the novelty of the Great Awakening is hard to understand. It is as if these principles of voluntary organization and popular assertiveness were always accepted truths in the Christian tradition as far back as the simple fishermen of the gospels. Yet nothing could be further from the actual setting of colonial religious affairs where inflexible rules governed who could speak in public settings, where, when, and to what extent. Like their Old World contemporaries, most American churchmen believed traditionally with the New England Purtian preacher Samuel Willard that God did ‘ordain orders of Superiority and Inferiority among men.’ In this hierarchical world view, rules of public speech were rigidly circumscribed and limited to an elite, college-educated ‘speaking aristocracy’ who would brook no interference from the lower orders. Public preaching and prayer remained the sole province of the established, tax-supported clergymen who had been set apart for their work by years of classical learning and study in the ancient tongues of the scriptures. The machinery of the civil state lay at their disposal to enforce orderly worship that stayed within the prescribed bounds. Voices from the lower orders – no matter how sincere and pious – were ruthlessly suppressed as usurpers who spoke out of ‘place’ or ‘station’ and, in so doing, threatened to ‘turn the world upside down’…

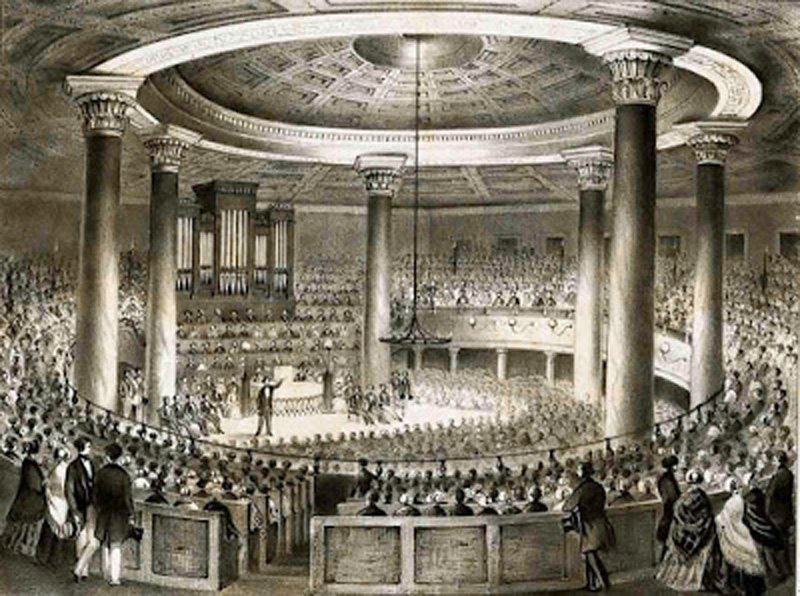

These traditional conceptions would be exploded by the first evangelistic tour of the youthful English itinerant George Whitefield. His celebrated journeys in the colonies stimulated an innovative style of communications that redefined the social context in which public address took place by encouraging the people to take direct control of their religious lives. In place of local congregations presided over by settled ministers, huge audiences suddenly materialized out of nowhere to hear the words of salvation articulated by travelling strangers whose only credential for public speech was their stated intention to proclaim the gospel. The sheer size and heterogeneity of the audiences exceeded anything in the annals of colonial popular assembly and, in a dramatic departure from existing modes of worship established by civil authority, were purely voluntary in origin. The established leaders had no special place in the revivals. If they attended at all, they participated in an extrainstitutional meeting that granted them no particular status or standing. Indeed, it was not uncommon to find Whitefield and his native-born disciples like Gilbert Tennent of Pennsylvania, James Davenport of New York, or Eleazar Wheelock of Connecticut actually attack opposing ministers and label them ‘unconverted formalists’ lacking in any ‘experimental piety.’ They could get away with such seditious speech only by virtue of their huge public following. And that popular following, in turn, discovered a power in their collective association that they never before knew existed. In a New World environment lacking the coercive controls of a monarchy, aristocracy, or powerful standing army, they found that they could defy existing institutional arrangements and there was nothing the authorities could do to stop them. It was a lesson that would not be forgotten.

To organize the mass meetings of the revival, both speaker and audience altered the roles and language they customarily adopted in public worship. The itinerant speakers preference for ‘extemporaneous’ address rather than written, erudite essays read from the pulpit attests to their desire to create a new sound in pulpit oratory that would speak to common people in their own idiom. And if everyday language could be sacralized, everyman could speak it. In the revival, the right to speak was a gift of the Spirit dispensed without regard to college training, social position, sex, or age: anyone was a potential public speaker (“The Transforming Effects of the Great Awakenining”, Eerdman’s Handbook to Christianity in America, 127-130).

As Stout explains, preaching was the dominant medium of public communication in the colonies. It required no literacy or education, and allowed for engagement with ideas outside of traditional restrictions of class, gender, and race. More, the appeal to large swaths of the nation presented a challenge to the dominance of the privileged. Outside of the institutional church, ideas emerged based solely on the consent of the governed rather than the will of the governors. Anything felt possible, once the constraints of oppression were cast off.

If the Great Awakening was about all of these things, which it clearly was, then the Second Great Awakening (1790 – 1840) was an effort to revive many of the mainline denominations that had become too powerful. The preceding movement was a political as much as a social movement away from the oversight of a distant monarchy. Day by day, by welcoming public displays of religiosity in public spaces, by encouraging emotional language and the story of one’s personal narrative of salvation in contrast to the reserve of Calvinism, a new kind of Christianity emerged, one greatly tied to ideas of nationalism and patriotism. These changes pressed the bonds of faith, creating cracks in many churches. Warfare had disrupted many congregations, particularly where fighting had been intense – New Jersey, New York City, Philadelphia, and the Carolinas. The Revolution had dealt an especially hard blow to the Episcopal Church, which was held at a distance and with suspicion for its ties to England. Once the Revolution was over, interest in religion declined and was replaced with enthusiasm for the new nation. Patriotism became a religion unto itself, enshrined in many congregations where it was allowed to wear the mask of Christianity.

The Second Great Awakening (1790 – 1840)

The Second Great Awakening occurred in several episodes, and inconsistently. The episodes were remarkably similar across different denominations, understood differently by divergent faith traditions. Broadly, people expressed a desire for something more. They spoke about these desires publicly. What got attention, the shift in cultural attitude, is that people found they were not alone in these desires. The Awakenings, plural, are often categorized as a period of religious revival and while this is true, it is also true that there have been times of alignment in the human experience. In admitting frustration with life, those actively being awakened or revived were able to acknowledge their shame, their sinfulness, and their hope for something more than drudgery and disappointment. During the First Great Awakening, Jonathan Edwards claimed that everyone was a sinner in the hands of an angry God. The entire generation and then their children were taught to believe that God was continually ashamed of them, that they were inherently and perpetually wretched, and that God only deigned to look upon humanity when the stench of evil could no longer be ignored. God was swift to anger and administer punishment. Coming out of the First Great Awakening, Americans forged a new nation but, once the fires of revolution had abated, the prevalence of Puritanical attitudes that remained had caused many Americans to suppress themselves, to live in a kind of quiet loneliness of suppressed experience.

Americans felt, at heart, spiritually lost as well as socially and at times politically forgotten in the runaway to build a nation. The Second Awakening’s emphasis on the individual experience, their testimony, made them feel like they mattered again, even if only to Jesus. Given language to articulate their anxieties, communities in the leadup to the Second Awakening continued to find those anxieties existed elsewhere. Curiosity and reinforcement of a shared experience spread, church to church, home to home, region to region. The most effective form of evangelizing during this period, revival meetings, cut across geographical boundaries. New evangelists and new itinerant ministers were able to spread stories of longing and hope, to speak of the need for a new mind and heart, of the possibility that God was once more speaking to this nation and wanting to do “a new thing.”

The movement quickly spread throughout Kentucky, Indiana, Tennessee, and southern Ohio, as well as other regions of the United States and Canada. By far, Methodists had the most efficient organization; their evangelistic efforts depended on itinerant ministers, known as circuit riders, who consistently visited and ministered to small, often remote congregations across the frontier. The circuit riders were often untrained, literate but not necessarily learned. They came from among the common people, often wore guns or at least rode with rifles, refusing clerical garb even when they may have earned it. Becoming familiar with the towns and people on their circuit, some helped with farming. They were not above helping to raise barns, hunt and trap their food, and listen thoughtfully to the concerns of their parishioners. They were “salt of the Earth” ministers, not the detached and disinterested clerics insulated by lifetime appointments in high society. The ruggedness of such ministers helped establish a rapport with the frontier families who they hoped to convert. Circuit riders didn’t talk down to their congregations. They didn’t claim that God was inaccessible or found somewhere else. God was here, among them, embodied in their folkways and customs. God was with them as they worked, as they rested, as they went about their quiet and unseen lives. There was no affection for the coldness and distance of clergy who preached a distant but sometimes benevolent God. Rather, Methodism emphasized the priesthood of all believers and, to that end, the pursuit of personal piety. God was always present, always invested in the lives of the believer, and wanted to help.

The Book of Nehemiah recalls a time when Nehemiah, a layman, was busy rebuilding Jerusalem when he was asked to give attention to visitors. Nehemiah responded, “I am doing a good work and cannot come down.” A life with God often meant hard work and there was nothing to be ashamed of in that. David was a shepherd. The prophet Amos was a tree farmer. Paul, the great minister, was a tentmaker. Jesus, the people needed to keep in mind, was a carpenter. The characters of the Bible were common and relatable. They were hard workers. It was a message that stuck. Except that rather than make allowances for the diversity of experience, once more, the Second Awakening began to assert a homogenous experience in which the customs and folkways that had been appreciated at the start of the revival would become more uniform and singular.

Western New York was still an American frontier during the early Erie Canal boom, and professional and established clergy were scarce. Many of the self-taught people were susceptible to the enthusiasm of folk religion. Evangelists won many converts to Protestant sects, such as Congregationalists, Baptists, and Methodists.

In the 1820s, alongside William Miller and Joseph Smith, Ellen G. White, and various utopian communities, New York State experienced a series of popular religious revivals that would later earn the region the nickname “the burned-over district.” Because of its small geographic range and close proximity to New York, where publishing houses were springing up each week and denominations had a stronger foothold to inspect and measure the revivals, records in the “burned-over district” are more reliable. The label implied that the area was set ablaze with spiritual fervor but it was not used by in the first half of the nineteenth century, as the revivals were taking place. The movements, plural, were still being observed, controlled, suppressed, even conditionally incorporated into the larger denominations.

The term originates from the Autobiography of Charles G Finney (1876), in which the popular preacher writes, “I found that region of country what, in the western phrase, would be called, a ‘burnt district.’ There had been, a few years previously, a wild excitement passing through that region, which they called a revival of religion, but which turned out to be spurious.”

Much of the knowledge historians have pieced together about the Great Awakening comes from personal records of those living on the frontier. This makes them inconsistent in language but consistent in their depiction. For this reason, it has often been overlooked by scholars who claim the records are unreliable because of the inconsistency of theology, language, or denominational investment. In fact, the first study of the phenomenon of the burned-over district was written much later by Whitney R. Cross in 1950 and not picked up again with scrutiny until 1984 with Linda Pritchard’s “The Burned-Over District Reconsidered: A Portent of Evolving Religious Pluralism in the United States.” Finney’s claims are, for the most part, supported by the records of the time that big changes were not just taking place in the booming cities of New York, Boston, and Philadelphia. Rural America was changing rapidly as a number of nonconformist folk religions and evangelical sects flourished.

Many of these new expressions and beliefs coalesced into various cults or what religious scholars would now call New Religious Movements. Most of these strands were an effort to recapture something important. Joseph Smith, for example, was eager to “restore” the Church. Some sought to redesign religious expression entirely. Many were utopian, complemented by religion but not necessarily beholden to any particular tradition. In the first part of the 19th century, more than 100,000 individuals formed utopian communities in an effort to create individual spiritual perfection within a harmonious society. Religious utopian communities sought “heaven on earth” like the Oneida Community in New York.

The Perfectionist movement came out of the Second Great Awakening and appealed to emotion. Founded by John Humphrey Noyes and his followers in 1848 near Oneida, New York, the Oneida Community sought a new understanding of Jesus’ teachings about love. They became convicted that society had become repressive, the fear and hardness of heart that had been so prevalent in Puritanism too focused on the fallen state of humanity. What religion needed to restore was a sense of freeness and openness, optimistically sharing with one another out of love rather than privately hoarding out of fear. The community believed that Jesus had already returned in AD 70; human activity had interfered and misunderstood Jesus’ final teachings. Noyes and his followers became convinced, like many other groups during the Second Great Awakening, that it was possible for them to bring about Jesus’s millennial kingdom themselves and to be “perfect” or free from sin in this world, not just in Heaven. This belief, Perfectionism, was quite prevalent and much of Methodism’s success in America was derived from the teachings of founder John Wesley who taught a “second blessing” of perfectionism in the Christian experience. The Oneida Community, unlike most Methodists, practiced communalism, or the sense of communal property and possessions. Whether this idea was authentic to John Noyes, one of his followers, or was derived from encounters with the traditions of First People remains debatable but the idea certainly held great attraction in New England. Ralph Waldo Emerson, the founder of Transcendentalism, and his acolyte Henry David Thoreau would both emphasize a connection to nature and the shared experience of all humans. What made Oneida unique was the extent of what was shared. The community participated in group marriages where mates were paired by committee. Children of the community were raised in common. Curiously, the community also encouraged male sexual continence, intended to bring the community closer through shared experiences and bond them to one another. However, in practice, these activities only served to raise questions about the legitimacy of their utopian intent. The community’s original 87 members grew to 172 by February 1850, then 208 by 1852, and finally 306 before dissolving in 1881, converting itself to a joint-stock company that eventually became the silverware company Oneida Limited, one of the largest in the world.

The Second Great Awakening was not as optimistic or free in its expression as the Oneida Community, however. In New York, William Miller was preaching apocalyptic messages that inspired the creation of the Seventh-Day Adventists and the Jehovah’s Witnesses, both traditions sharing Miller’s millenarian fervor. Miller was so convinced that the world was about to end that he predicted Christ would return to earth in 1843 or 1844. The failure of his prophecy, the so-called “Great Disappointment,” did not deter many of his followers, who still believed in his preaching and predictions despite their obvious failure. The “Millerites” defended their commitment to his teachings by admitting while Miller’s calculations were faulty, the return of Jesus was still imminent. Miller was ultimately so influential to American religion that historians can trace the emergence of Evangelicalism’s emphasis on the imminent return of Christ to judge the world back to him.

Seventh-Day Adventists, formed under the leadership of one of Miller’s followers, gave way to the prophet Ellen G. White, who co-founded the religion while authoring books on the health benefits of vegetarianism, proper childcare, and church history. According to White, she received over 2,000 visions or dreams from God; convinced that while leaders of the Church may have wanted to silence the miraculous and better enshrine institutionalism, or even dismiss her because of her gender, God was still alive and active in the hearts, minds, and lives of believers. She verbally described and prolifically published for public consumption the content of each vision. Early Adventist pioneers held these experiences up as evidence for the Biblical gift of prophecy as outlined in the book of Acts, the Pauline epistles, and the book of Revelation. White and her fellow Adventists also devoted a lot of attention to in her writings to the “Great Controversy”. Her “Conflict of the Ages” series showcased the hand of God in Biblical history and church history as an ongoing cosmic conflict, the “Great Controversy,” which became foundational to the development of Seventh-day Adventist theology. Christians were not asked to passively witness the war between good and evil, but engage in it and fight against darkness wherever it may be found – including the Church. Remarkably, White’s influence within the Seventh-day Adventists made space for the ordination of women in other denominations.

The extent to which religious fervor actually affected the region was reassessed in the last quarter of the twentieth century. Linda K. Pritchard used statistical data to show that compared to the rest of New York State, the Ohio River Valley in the lower Midwest, and the country as a whole, the religiosity of the Burned-over District was typical rather than exceptional. More recent works, however, have argued that these revivals in Western New York had a unique and lasting impact on the religious and social life of America. Converts in nonconformist sects became part of numerous new religious movements, all of which were founded by laypeople during the early 19th century. Still, as Cross and Pritchard point out, the Burned-Over District included other popular religious movements like

- The Latter-Day Saints (whose largest branch is the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints), originated circa 1828. Joseph Smith, Jr., lived in the area and said he was led by the angel Moroni to his source for the Book of Mormon, the Golden Plates, near Palmyra, New York.

- The Fox sisters of Hydesville, New York, conducted the first table-rapping séances in the area around 1848, leading to the American movement of Spiritualism or communion with the dead.

- The Shakers were very active in the area, establishing their communal farm in central New York in 1826, and a major revival in 1837. The first Shaker settlement in America, also a communal farm, was established in 1776 just north of Albany.

- The Social Gospel was founded by Washington Gladden while he was living in nearby Owego, New York, during his childhood and teens, circa 1832 to 1858.

- Transcendentalism was a philosophical, spiritual, and literary movement developed between 1820 and 1830 by former minister Ralph Waldo Emerson and several of his followers.

- The Ebenezer Colonies, calling themselves the True Inspiration Congregations (German: Wahre Inspirations-Gemeinden), first settled in New York near Buffalo in what is now the town of West Seneca. However, seeking more isolated surroundings, they moved to Iowa (near present-day Iowa City) in 1856, becoming the Amana Colony.

Such groups, made up of utopians, apocalyptics, nature-lovers, self-proclaimed prophets, abolitionists, women’s rights advocates and advancers, utopian social experiments, Mormonism, and vegetarians were the sort of lot that revivalist Charles Finney felt were “spurious”, offering a false message of hope. Finney wrote in 1876 that

It was reported as having been a very extravagant excitement; and resulted in a reaction so extensive and profound, as to leave the impression on many minds that religion was a mere delusion. A great many men seemed to be settled in that conviction. Taking what they had seen as a specimen of a revival of religion, they felt justified in opposing anything looking toward the promoting of a revival.

The issue then was that they were rivals of what Finney saw as true revival, the kind he offered people. The inability of these movements to create lasting change should have been testimony against them, but instead, it was that Finney took issue with them personally and brought questions of legitimacy to his own revival efforts. It is true that such movements broke apart easily, reformed, and spread at such a rapid rate that a member of one group would reappear later in a church, even one of Finney’s own revival meetings. They were a poison in the living waters he offered true Americans, their only hope of salvation – true salvation – coming from his own preaching.

It is curious then that Finney subscribed to so much of the “spurious” teachings such groups put forward. Like other American reformers of the time, Finney rejected much of traditional Reformed theology, openly opposed “old school” Presbyterianism, and the Puritanical attitudes of shame and obedience in the churches he grew up in. Finney was best known as a passionate revivalist preacher from 1825 to 1835 in Upstate New York and Manhattan, as an advocate of Christian perfectionism, and as a religious writer. His religious views led him, together with several other evangelical leaders, to promote social reforms, such as abolitionism and equal education for women and African Americans. Retiring from the strains of ministry, he joined Oberlin College of Ohio, which accepted students without regard to race or sex, before becoming the school’s second president from 1851 to 1865. Installed at Oberline, a deeply liberal school even today, its faculty and students were activists for abolitionism before joining the Union Army. Many of them helped with the Underground Railroad and promoting universal education, without regard for race, gender, or class. As for Upstate New York, the “burned over district,” many historians see the label as indicative of Finney’s rivals as well as Finney himself. Though he only held revivals for ten years, the region was “lit aflame” during the Second Great Awakening and reignited the Third Awakening.

More than anyone else, Finney’s ministry inspired Jimmy Swaggart. Finney was active as a revivalist from 1825 to 1835 in Jefferson County and for a few years in Manhattan. Known for his extemporaneous preaching, which felt fresh and timely, he led a revival in Rochester, New York, from 1830 to 1831 which has been noted as inspiring other revivals of the Second Great Awakening. A leading pastor in New York who was converted in the Rochester meetings gave the following account of the effects of Finney’s meetings in that city: “The whole community was stirred. Religion was the topic of conversation in the house, in the shop, in the office and on the street. The only theater in the city was converted into a livery stable; the only circus into a soap and candle factory. Grog shops were closed; the Sabbath was honored; the sanctuaries were thronged with happy worshippers; a new impulse was given to every philanthropic enterprise; the fountains of benevolence were opened, and men lived to good.”

Finney was known for his innovations in preaching and the conduct of religious meetings, which often impacted entire communities. Innovations included having women pray out loud in public meetings of mixed sexes, the introduction of the “anxious seat” in which those considering becoming Christians could sit to receive prayer, and public censure of individuals by name in sermons and prayers. Finney “had a deep insight into the almost interminable intricacies of human depravity…. He poured the floods of gospel love upon the audience. He took short-cuts to men’s hearts, and his trip-hammer blows demolished the subterfuges of unbelief.” In time, similar assessments would be made of Jimmy Swaggart who was a consummate showman. Swaggart would pace the stage like a predator, crying and laughing and wagging his finger before interruptting himself by assuring his audience that he loved them, but that God loved them more and that was the only reason why he was on the stage, on their televisions, traveling the world.

Historians and theologians are still trying to parse the Second Great Awakening, the impact of that half-century on culture, politics, gender, theology, marriage, diets, politics, existential concepts of life and purpose, salvation and sin, cultural trends and the responsibility of the individual within society. It is truly difficult to trace these when, again, so much was happening so quickly in such concentrated areas and when the majority of records are personal and anecdotal. What is clear, looking at the impact of these events, is that such groups would give birth to the Evangelical Movement broadly and Pentecostalism specifically.

Jimmy Swaggart could claim to receive salvation, be filled with the Spirit of God, and predict the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki because the Second Great Awakening allowed for many new religions and new expressions of older religions to come about. The Pentecostal Movement was part of the third wave of religious movements that would revive America. As the nation entered a new century,

The change that was perhaps most telling for the sort of white Protestants that had dominated nineteenth-century religious life is the United States was a simple statistic. In 1870, 9,900,000 Americans (or 26 percent) lived in towns and cities with 2,500 people or more. By 1930, the absolute number had risen to 69,000,000 Americans and the national proportion to 56 percent. The shift in population to the cities did not mean that revivalistic, evangelical, voluntaristic Protestantism passed away. But it did mean that the small towns and rural settlements where Protestantism had dominated culture as well as provided the stuff of religious life were no longer as important in the nation as a whole. The urban environment provided more intense commercial pressure, greater access to higher education, and more opportunities for contact with representatives of diverse religious and ethnic groups – all of which worked in some degree to undermine the evangelical character of the national religion. Space in the cities for other forms of Christianity and for simple inattention to the faith stimulated the religious pluralism that had always been part of the American scene. It may have been that these sorts of social changes were the primary reasons for the shaking of white Protestantism in the period between the Civil War and World War I. But changes of this kind were also matched by intellectual dislocations that testified to the fragmentation of the Protestant Christianity that for a century or more had dominated public religion in the United States. (Noll 364)

One thought on “Biography: Jimmy Swaggart, Chapter 2(a)”