by Randall S. Frederick

By now, we’ve come to the front door. Once we cross this threshold, we’re no longer talking about the outside world, the outward life, but the inner one. Whether you inhabit a space where you feel boxed in or feel free to talk about everything publicly, the front door is that superficial barrier to the real you, into your sense of safety and honesty. There’s no judgment about what kind of person you are. Introvert and extrovert, private and open, these are labels that are not always consistent. My wife is more outward-facing than I am, even at times with her family, but this does not mean she is superficial or that my need for privacy is a virtue.

Don’t be alarmed yet. I’m not going to suggest that by crossing this imaginary threshold, the one you’re envisioning, we are now our fully realized selves. Far from it. I do not require that you begin to strip away the Outside World in your mind. Rather, I would like to offer the suggestion that by considering a front door, you might meditate on the first barrier to your inner life.

The Front Door

My wife admires blue doors. By this, I mean that she points them out when we drive through neighborhoods. She has a “favorite door” in our hometown that she points out to friends who visit us and, no surprise, it’s blue. On lazy weekends, even busy ones for that matter, we sometimes walk through lumber stores on our latest DIY fixation and she admires doors. Driving through neighborhoods, she’ll point out the placement of windows on a door, how trim or frames accentuate the door, where a handle is located, and whether it “matches” the design and color.

What I mean is that our front door is blue.

So is our back door.

If we had a side door, I’m sure that would be blue also.

I also mean, keeping my wife’s approach to doors in mind, that I notice none of these things. The door is a superficial barrier to me. It doesn’t matter what it looks like, really. It’s a door. Come on, let’s not overthink this just to stretch the page count, right? What matters is not the portal, but the two sides of the portal, the coming and the going, the inward and outward. My wife is more inclined to notice the in-betweens, to be mindful of the transitions. She is more inclined to pause and reflect, to analyze and allow her curiosity to ask what the placement of a door handle or window says about the people on the other side of the portal.

Doorways were considered magical, once. Imbued with power. A character in a book or play stepped through a portal and they were off to a magical land, sometimes even trapped there in the unknown realm because of their hastiness, because they did not stop to consider where the door would take them. While I’m less inclined to believe that, say, the white doorframe of your home transports you into a magical realm, as someone who studies literature, I’m inclined to challenge you to think more broadly about why and how authors and folklorists imbue doors with meaning.

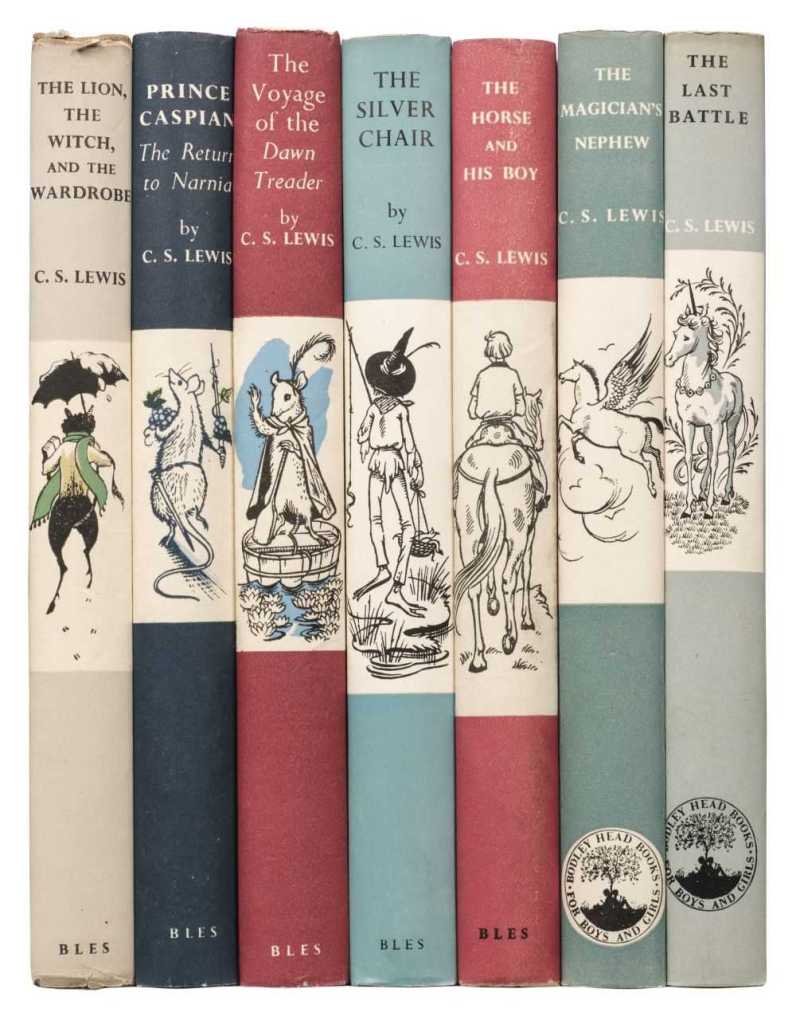

What magic do we bring with us when we go places? Doorways and portals in general tend to work both ways, we should note. In The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, one of the Pevensie children hides in a wardrobe — a piece of furniture — and discovers a door there. At the end of the book, a lifetime has passed. The Pevensie children are all grown up, experienced, and wise because when they crossed that threshold they were children.

When they returned through it though, so much had happened that they were hardly the same people. Each of the children return to the world that they left those many years ago and are now faced with a choice. Are they truly wiser and more experienced, old souls given a second chance in their younger bodies? Or do they revert to what their younger bodies insist to be true, that they are children who were playing at adulthood and that their experiences were just a dream?

Lucy, the youngest of the family, spends the years after her return knowing that the world is decidedly smaller, lesser, weaker, less magical. When she is given a chance to return, she eagerly goes back to Narnia. Susan, the older sister and nobler queen in Narnia, thrives in the normal life of a teenager. She returns to school and finds that she enjoys the reduced duties of a life without royal concerns of state. Susan sets aside the crown for a simpler life, one of lipstick, nylons, and boys. Literary critics and theological readers will note the progressive loss of faith and belief, the loss of magic, in Susan’s life. Despite living in Narnia, despite witnessing its power and wonder, she loses confidence in its magic. How is that possible, we might wonder?

Peter and Edmund, Lucy and Susan’s brothers, experience their return to the real world differently as well. Peter continues to study the possibility of other worlds. He returns to Narnia on occasion, but only as a visitor. At the end of the seventh novel in the series, Peter discovers that the Narnia he knew was only a small part of the cosmos. He had never tried to build a bridge between worlds, or even bring Narnia to Earth. Peter’s life, instead, is the devotion to studying what is possible and in this way, he is the one most able and adept at moving between the two worlds because he is not consumed with the task. He lives his life, in other words. Edmund, in contrast, tries to do this same thing — to live his life with the awareness of two worlds, but not be consumed by the effort to return. At the end of the series, Edmund dies in a train accident. So does Peter. So does Lucy. Susan, the only one who turned her back on the magical world, is the one who survives the events of the story. The door is not closed for her, necessarily, but unlike her siblings, Susan has found a way to enjoy her life and be satisfied without always looking to the next thing.

This is the power of doorways: we have a choice, yes. But the power of choice is only one aspect. How we organize and build our lives on one side of the door or the other is worth paying attention to.

Please correct me if I’m wrong on this because I would love to hear your story, but I believe it is a safe bet that most of us have not gone to magical realms with talking animals. We have not found doorways in the back of our closets or wardrobes, been gifted with magical rings with which we can visit magical realms and talk to magical people. But that doesn’t mean doorways, the door itself, is any less magical when we stop to consider it. As Lewis’ friend J.R.R. Tolkien wrote in The Lord of the Rings, “It’s a dangerous business, Frodo, going out your door. You step onto the road, and if you don’t keep your feet, there’s no knowing where you might be swept off to.”

Most of us, I’m guessing, live quiet lives of desperation on one side of the door or the other. When we are at home, we feel anxiety and depression, we “veg out” and self-medicate. When we are away from home, we feel that same anxiety and depression, we still self-medicate and “space out.” Whether at work or on a lounging chair beside a pool scrolling through social media, many of us are aware that the “real life” we are living is not as magical as we might have hoped when we were younger. Even the screens of our phones, tablets, and laptops are a portal of sorts and we prefer to stay on the far side of it, enraptured with wonder at other people’s lives. Good things only happen to people on the other side of these doors.

Circling back to the contrast between my wife and I, my personality is inclined to see pain on one side of the door as much as the other. My wife enjoys focusing on the door itself, but who we are and how are we in the in-between is just as important. She focuses on balancing the two, reminding herself that both are important, that there must be a level of authenticity to be found on either side. Her mother, in contrast, is far more optimistic than either of us in daily life. She believes pain exists, yes, but there is no sense in lingering with it. Instead, life should be lived with joy and whimsy, recognizing that while pain may exist, there is also possibility on both sides of the door, the inner and outer life. Life comes with challenges, but those challenges are an opportunity, not a threat.

Whatever our personality or natural inclination, we live in two realms and the doorway compels us to consider this. One part of us has been changed and infused with magic and experience, the other lives out a normal, typical life.

Like Lucy, we feel a churning sense of confusion. There is a world out there, somewhere, that no one else can see. How frustrating.

Like Edmund, we might be a little better at suppressing this. We look to inspirational people, like Edmund looks to his older brother Peter, for inspiration. We are able to move between the two worlds a little more easily and successfully. But the frustration is still there, it’s just hidden a little better than it is with Lucy. More reserved, we don’t feel a need to go about insisting to anyone who will hear us that “real” life is small and boring. It is enough to know that another world, another life exists somewhere else.

We might be like Peter, who devotes himself to bridging the two worlds within himself, to live in a present, conscious way whether at home or outside of it, only to find in the end that a larger, better world was possible than what we had ever realized. This does not feel like a disappointment so much as an admirable commitment. Peter does his best, aspires to greatness, only to find at the end of his life that his dreams may have been comparatively big but were actually quite small.

Or, like Susan, we might find the constant search for meaning and significance to be unsustainable. Seemingly, we “give up” and live life in the best way we know how even if that appears to be superficial to those who are slowly being driven mad by the search for magic in their lives. We focus on the here and now, not the innocent wonder of youth. This life is enough, day to day. You’ll only waste your life trying to recover the wonder, beauty, and idealism of youth. Like Susan, we may just accept that the portal — the very premise of this entire argument — was the origin point for a great deal of unwanted anxiety.

Friend, I hate to belabor a point here and cause your brain to ache. But when was the last time you considered the portals of your own life? Those ignored moments you have passed through without considering them, the dividing points of change, the transitions you have experienced that reoriented your life?

There’s nothing wrong with living a normal, everyday life. Normal is not somehow less important. Indeed, I wonder if our fascination with magic and fantasy — in books, on social media, pushed down and silenced inside of us as unexpressed longing — has diminished us, exhausted us, or caused us unnecessary anxiety. Because doorways are portals, yes. But sometimes they are just doors. In life, stuff happens. Transitions happen. No need to overanalyze it and mine routine, daily activities to make them more important than they really are.

The Pevensie children-turned-adults chose to return to their normal, daily, even disappointing lives. So let’s not make the magical more important than it is or insist that each of us is magical or that we should aspire to live in that heady, eternally youthful realm of the imagination forever and ever.

Remember the stories you grew up with. Most of the characters, when given the choice, leave the world of magic. Dorothy leaves Oz because there is “no place like (the dull, humdrum, miles of farmland that still needs to be worked each day) home.” Harry Potter, you will notice at the end of the last book, has chosen to raise his children in the normal world where they will need to ride a train to school instead of getting there by magic. Brooms, flying cars, floo powder, portkeys, there are a lot of options available, but Harry and his wife Ginny as well as every other adult who knows about the mundane and the magical world, even the morally dubious Draco and his wife, seemingly chooses to send their child off the normal way, through a train. Or a bus. Or a short walk.

Which is to say that doorways are a liminal space, a between space, that many of us — myself included — often overlook and take for granted. Every day, we have a choice. Every day, we dress up and become who and what we are, and we accept the routine of daily life, and the portal is still there. It’s almost as if these stories have a secret clue for us, that we can choose to set aside the magical and go on living. Or perhaps that the everyday things like buses and trains, being in relationships or even getting married, and having children who bicker and tease one another are magical too.

There’s nothing wrong with you and you have not failed in any way if you are living a non-magical life. The portals still exist, the doorframe is still there. The children can still ride the magical train to the magical realm. Or ride the Magic School Bus into a world of rational explanations. Or take a walk to enjoy nature. Considering the Pevensie family after they have left the magical realm behind, we might notice a few things.

The portal was never the point, as I maintain. The portal brings attention to who we are, as my wife maintains. We were never at odds with one another on this. Study and action became the life of the oldest brother Peter. Emulation and attention became the life of Edmund. For Susan, her life was one of rejecting the premise and finding joy in regular life. For Lucy, it was eagerness and anticipation for whatever the next adventure may be. Each of these exemplifies how we respond to the portal of a doorway and, I would venture, how we orient our thoughts and organize our lives as we move between worlds. The Pevensie children-turned-adults were still heroes and heroines. They had been all along. Whether on one side of the portal or the other, they were still themselves and their experiences still defined them.

So the dual worlds in the examples I am using and the metaphors I am building, are not merely between daily life and home life, the horizontal balance between work and home. It is also vertical, like the Pevensies and Potters and most other literary explorations. We are in a constant pull, those reading a book like this, between the spiritual and quotidian. The doorways of our lives are not merely between the magical and mundane, but the practical and spiritual.

I want to stop, before going any further, and ask you to do something with me. I hope it won’t feel too solicitous to you. I want to ask you to hold this tension. If you have already determined what kind of person you are, that is well and good. No magic for you, or perhaps having taken the other road entirely, you may be entirely whimsical without any interest in this so-called reality I’ve been talking about with its unflattering routines like washing clothes and accounting. But for those of you who feel, more appropriately, that you are still stuck in the doorway and undecided about whether you wish to go any further, I would again ask that you hold the tension for a bit with me. It is possible, I assure you. As possible, I imagine, as thinking about work when you are seated in your home or vice versa. One does not have to decisively be in one dock or the other, precluding or excluding or even preferring one against the other. When I started this piece, I told you as much. I am not trying to guide you anywhere that you would not naturally go yourself, of your own accord. Rather, I am trying to get you to slow down long enough to process a few things and reflect on the outward expressions, the outworkings mind you, of that inner life.

From here, we must really begin to discuss this inner life with its complexities and idiosyncrasies and this will be, I suspect, a tender thing. It is for me, anyway. That’s why I am so private about my inner life. There are many days when my wife asks what I am thinking and I evade with some lighter, more conversational answer. She often asks what I am feeling and I ignore the question. It is a tender thing, the inner life, and I do not want to disturb anything anymore than I would wish to enter your home and toss things off the shelf without your permission. I wish to be a humble guest, if anything.

Still, here we are at the door and if by now you’ve grown bored or uncomfortable with me “on your porch” or “at your door,” it’s perfectly fine to not answer. After all, you don’t know me very well and if what I have written so far causes alarm, then it is reasonable to not continue the conversation, to refuse to open the door and allow me to go knock somewhere else.

What I am asking you to do, Reader, is let me in for a bit. Give me a tour of your home, where you live, and feel free to point out anything important to you if you feel I’ve overlooked it.

The Livingroom

Who we allow inside our living room, more so than the porches and walk-ups of our homes and apartments, is a good indicator of who we are and how we are living our lives. In my living room, there is a sofa and a television set, some books, and a wine cabinet. For better or worse, this sums up a great deal of my wife and I’s marriage. I collect books, she collects wine, and occasionally we share these with friends on the sofa. Most nights, we watch a show or a movie, decompress, and try to go to bed by nine o’clock, although as I write this, we’ve spent a few nights this past week up late watching a show on a streaming service that has captured our attention.

These pieces of furniture are set pieces. Cross over the threshold through the doorway and you see the indicators of a life, but not the life itself. You see, the living room is also where my wife and I tend to argue. It’s where we entertain. It’s where we have cried about loved ones we have lost. It’s where we eat dinner, sometimes. Where we check in with one another, talk about work and life plans, where we find a curious amount of hair. When I wake up in the middle of the night with anxiety, which is more frequent than I would care to admit and far more than I would prefer, I will sleep on the sofa in our living room, or read, or (if I am simply unable to fall asleep again) play video games.

The living room, it turns out, is a universal catch-all. Maybe we are entertaining. Maybe we are lounging and vegging out. Maybe we’re zoned out on our devices, scrolling social media. Maybe we’re scrutinizing menus trying to decide what to have for dinner. But the living room and what happens there hits multiple angles and at any given moment of any given day, you might find one or both of us simply venting about the frustration of being alive during a time of such upheaval.

Who we allow into this space is a tender thing. I’m more of an introvert and far more private than my wife, so there are certain people I have forbidden from crossing the threshold into our home. There are people I allow in with caution, previous agreements that so-and-so be watched carefully. Other people are free to come and go as they please for the simple fact that their lives are shared with ours. They know the shows we watch, they’ve sat on the sofa with us and cried, they are welcome wherever we are and to ask whatever invasive question comes to mind.

But this is not always the case, is it? I suspect you know the feeling of this space being violated, even in a polite way.

Last year, my mother bought a home and in the process of moving in, a neighbor came to visit her and welcome her to the neighborhood. Tromping up the steps, he was a bit winded and I suppose empathy as much as the physical and mental exhaustion of moving her had taken its toll on me. He knocked and I was the one who answered. Winded, he said his name and then bluntly told me to let him in. This was a mistake. You see, this was not my home, it was my mother’s. And I can only explain — not defend, but explain — these reasons for why he was allowed in. I regretted it instantly. My mother was angry. My father, her ex-husband, was also there and even he was a bit put off as the neighbor began to tell us what we “needed” to repair and offering to us that great gift of all paunched white men everywhere, “Here’s what I would do if I were you.”

He told us about the people who had lived there previously, how “dirty” they were, that he suspected them of being “drug addicts.” Then, perhaps encouraged by our silent shock, began to tell us his political views. He asked whether my mother had a gun. At which point I came to my senses and, trying to be civil, said we were all rather tired. With a smile, I said whether my mother had a gun or not was really (no, truly, no no, truly sir) none of his concern. “I think we’re all a bit tired from the day, so we’ll let you go back home.”

With promises to “come back and shoot someone if you need me to,” he left and I think we entered into a silent pact to never mention this terrible mistake again, to never allow him to cross the threshold of the door a second time. He had steamrolled in and, even though his visit began with politeness and concern, it was clear that he had violated something by overstepping himself.

There is something expansively intimate about the living room, perhaps because it is the location of so much of the traffic of our lives. We entertain and host, we share secrets and tears, we laugh and tease, we plan our finances and affairs there, and we even sleep there, as I do on occasion. But who we hold space with, who we let into our lives says as much about us as them. Allowing them in, even here at the introductory level, is sometimes a mistake. This first step into our world, into our space, allows for a first glimpse into who we are and how we orient our lives. If the guest fails here, there’s no point in allowing them to go any further. Designer Tayyaba Aijaz Jafri helps us understand the importance of living rooms in the home.

The living room is often considered the heart of the home and for good reason. It serves multiple purposes and is the central gathering place for family and friends. This is where people spend time together, have conversations, and make memories. Whether it’s watching a movie, playing a game, or just hanging out, the living room is the place where people come together to relax and socialize.

Tayyaba Aijaz Jafri, “Four Reasons Why the Livingroom is the Most Important Part of Your House”

Additionally, the living room is typically the first room that visitors see when entering the house. It is often used as a representation of the homeowner’s personal style and taste. A well-decorated and welcoming living room can make a great first impression on guests and make them feel comfortable in your home.

The living room is a versatile space that can be used for a variety of activities. It can serve as a television room for movie nights or a gaming room for family game nights. It can also be used as a reading room, a music room, or a place to work. The possibilities are endless, and the living room is a space that can adapt to the needs of the homeowner.

Finally, the design and decor of the living room can greatly impact the overall atmosphere and aesthetic of the entire house. The color scheme, furniture, and accessories all play a role in creating the desired ambiance. A well-designed living room can make the entire house feel more inviting and comfortable, while a poorly designed one can make the house feel uninviting and unwelcoming.

What is the image you present to people? Yes, the clothes you wear but also the more socially acceptable personality you present.

My grandfather, my father’s father, was a terrible person. I don’t mean that subjectively. I mean by any measurable standard, he was repugnant.

My father’s mother died when he was five years old. She was pregnant with my aunt and my father somehow knew she had died before anyone told him. When he came home from school, he saw all of his things on the curb. My grandfather felt that since “the bitch was dead” he didn’t want “the pups”, his own children.

My aunt was given to a cousin and her husband, while my father was given to my grandmother’s mother. My grandfather visited her regularly, including him in his new family. As my father grew up, he rarely saw his dad who by that point was an active leader in the Ku Klux Klan outside of Baton Rouge. My grandfather remarried and, as my father heard it, was physically abusive to his new wife. When he was old enough, relatives began to explain to my father that his mother could have survived. She was young and healthy when she went into labor. But she had recently learned my grandfather, her husband, had been having an affair. It wasn’t the first time. Married to a physically abusive husband who habitually cheated on her in a Catholic community that forbade divorce, she felt she had no options, no way to escape except through death. I’ve often thought about the stories my father has shared with me. As well as the ones that were never shared with him. Shortly before he died, my father’s parrain (what the French-speaking Cajuns of South Louisiana call their godfathers) told him that there were still things he hadn’t been told. His father, it turned out, was a terrible husband, father, and an open racist, but some things were left unsaid because they were even worse than this.

To those who didn’t know him personally, my grandfather was an upstanding citizen. He often insisted that he was charitable, “as long as people don’t ask for help.” It was seemingly true. He was quite the charmer. An outdoorsman, professional racecar driver, and expert pipefitter in a region of the state experiencing a rapid increase in the number of oil refineries, my grandfather died a wealthy man. His living room had an excellent sound system, luxurious recliners, and one of the biggest televisions available outside of a professional film studio. His living room, metaphorically and literally, was meant to impress. Only he had no friends. By the time he bought his last house, everyone knew the racist man down the street. They avoided him. He never let anyone in, not even his own family, as he wound down his final years. The con was over. He couldn’t big-screen TV his way out of things anymore. When he died in 2011, there was no service. He and his wife knew no one would attend. Instead, he donated his body to science. Months later, in a service commemorating the deceased in the community who had died alone, my grandfather’s photo was briefly shown in a PowerPoint slideshow. His wife had already packed up and left for California. His other daughter, my aunt, didn’t attend either. The only person who attended was my father, “the pup” he didn’t want.

The person we present to the world, to outsiders, is remarkably different from who we truly are. There are pieces of honesty, sure. The photographs and furniture speak to a sense of style and our ability to bring it all together, to curate our lives in a presentable way. But can you say, with integrity and honesty and transparency, that you are your fully realized self with everyone, even strangers? We’re adaptable enough to entertain for short periods, but eventually, we want the guests in our lives to leave so we can relax and be ourselves.