Prologue

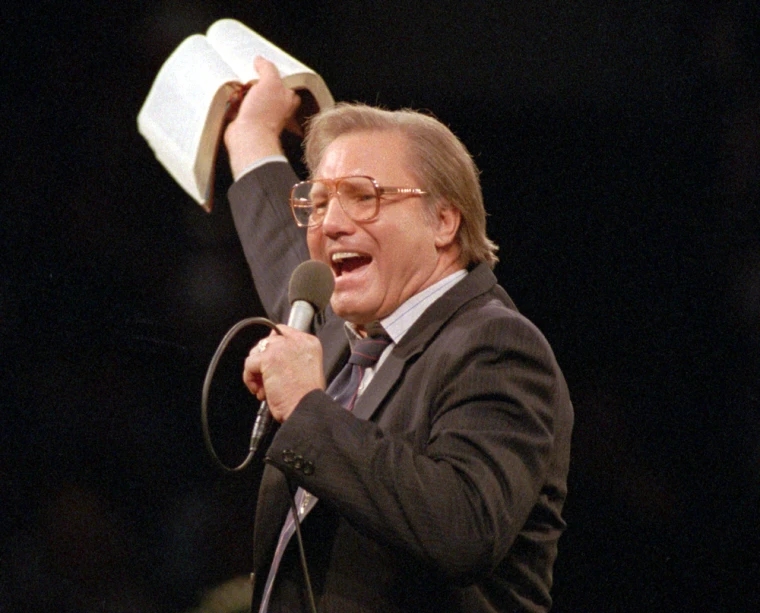

Time is not kind to those who have failed in a public forum. This truism only becomes more complicated when religion is involved. Above all, when they are famous. Jimmy Swaggart, once the most famous evangelist in the world, tearfully and earnestly admitted his failure on February 21, 1988. He had been caught visiting a prostitute and, in an attempt to get ahead of the story, he admitted to a series of unspecified sins that almost everyone in attendance at Family Worship Center in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, had already heard or read about in the preceding days. “Everything that I will attempt to say to you this morning,” he began, “Will be from my heart. I will not speak from a prepared script. Knowing the consequences of what I will say and that much of it will be taken around the world, as it should be, I am positive that all that I want to say I will not be able to articulate as I would desire…. I do not plan in any way to whitewash my sin. I do not call it a mistake, a mendacity; I call it sin. I would much rather, if possible — and in my estimation it would not be possible — to make it worse than less than it actually is. I have no one but myself to blame. I do not lay the fault or the blame of the charge at anyone else’s feet. For no one is to blame but Jimmy Swaggart. I take the responsibility. I take the blame. I take the fault.”

Each gasping sob reverberated across the social landscape. Millions were glued to their televisions, even watching it again and again as the show was repeated multiple times in syndication and through television news. The apologies that followed were addressed to his wife, his son, and his daughter-in-law, all three in attendance, before asking for forgiveness from the Assemblies of God denomination and the “thousands and thousands of pastors that are godly, that uphold the standard of righteousness, its evangelists that are heralds and criers of redemption, its missionaries on the front lines…holding back the path of hell” before turning to “This church [Family Worship Center], this ministry, this Bible college [Jimmy Swaggart Bible College], these professors, this choir, these musicians, these singers that have stood with me on a thousand crusade platforms around the world,” his fellow televangelists, “and to the hundreds of millions that I have stood before in over a hundred countries of the world, and I’ve looked into the cameras and so many of you with a heart of loneliness, needing help, have reached out to the minister of the gospel as a beacon of light. You that are nameless — most I will never be able to see except by faith. I have sinned against you. I beg you to forgive me.”

He then began to conclude, “And most of all, to my Lord and my Savior, my Redeemer, the One whom I have served and I love and I worship. I bow at His feet, who has saved me and washed me and cleansed me. I have sinned against You, my Lord. And I would ask that Your precious blood would wash and cleanse every stain, until it is in the seas of God’s forgetfulness, never to be remembered against me anymore.”

The apology was all-encompassing to all of Christendom, in this life and the next. Yet in the eyes of the American public, his “stains” would remain. Swaggart became a byword for moral failure, ruin, and hysterics. In terms of public humiliation, no one had self-destructed in front of so many people. Then again, no one had made such an all-encompassing apology before either. No one had sought forgiveness this way, openly sobbing with apologies and requests for forgiveness. It was, to put it lightly, a defining moment in American television. Politicians would follow Swaggart’s example, allowing themselves to admit personal failures, to apologize, even doing so through tears. In the months ahead, given the size of his regularly returning viewing audience together with the curious and the critic, the pundit and the pastor, the far-reaching impact of his ministry, the curiously unnamed nature of his sins immediately became fodder for exaggerated rumor and gossip. The actual sins, though they were significant, began to define Swaggart’s legacy. Forgotten were the goodwill and public trust he had accrued, the moral high ground he had secured. Forgotten were the ministries and missions he had funded. Forgotten were the filled amphitheaters with their orchestras and the high production values of his traveling shows, his Campmeetings, conferences, and concerts. Forgotten were the bestselling albums and awards, the radio programs and television shows, books and teachings on cassettes. Forgotten were his meetings with political candidates and Presidents, the primetime specials, the stadiums all around the world where he delivered food, dug wells, built schools and hospitals. Forgotten were the thousands of jobs and millions in tax revenue he had brought to the State of Louisiana, his startup Bible College with over a thousand students just down the road from Louisiana State University, the towering dormitories, the educational complex and gymnasium, the fields of surrounding land dedicated to growing the ministry in the coming decades. Forgotten were the lives he had touched and changed. Forgotten was all of this; association with his ministry was now something to hide, to sidestep, to erase. To forget.

Jimmy Swaggart had sinned. He admitted as much. But the specifics – prostitution, financial malfeasance, slander, libel, manipulation and maneuvering, elimination of opponents as frequently as colleagues or so-called friends, arrogance rivaling that of his cousin Jerry Lee Lewis, and the self-righteousness that had come to define him even as it bordered on the delusional – were less clearly articulated. Though the apology had covered everything in its generality, it was still not specific enough. He had self-destructed but had failed to carve to the bone, to peel the fat from the flesh, to light himself aflame in sacrifice. He hadn’t named his sin, hadn’t been specific enough; admitting one’s sin, naming it, was important in seeking repentance.

Almost immediately, Jimmy Swaggart Ministries began to lose donations. In the weeks ahead, thousands of churches, missionaries, and other ministries would lose financial support as well. Swaggart’s admission was so radioactive that it damaged ministries not even related to his own. America lost interest in religion. If the biggest, baddest, boldest, brassiest preacher on television and radio was a sinner like them, in some instances worse, then what was the point of listening to him or any of the rest of the televangelists hawking their wares along with other infomercials? Swaggart, it appeared, was not special. He was a commoner, like everyone else. Worse, if the rumors were to be believed. Shamed and brought down, he was exposed as a hypocrite and a liar.

The great tragedy of Jimmy Swaggart is that this was not true. He was a sinner, like everyone else. That was true. Only his sins were more public than his viewers. The tragedy is that he was right about a great many things. His criticisms were, at times, vicious, but those same criticisms were proven correct with time. The messenger may have been compromised, but the message itself remained intact.

From salvation to scandal to seclusion to statesman, Swaggart has remained an icon, mainly because he has always been outside of the trends of Evangelicalism, continually questioning them and provoking conversation. Like every great entertainer, he could read a room and give the people what they wanted. Even now, at the twilight of his life, having navigated scandals and the subsequent collapse of his ministry, Swaggart knows how to remain responsive to trends. In the Nineties and Aughts, his ministry was able to rebuild from the wreckage. Having lost everything, even his name, but continued to move forward and slowly acquired radio stations across America. Through donations and gifts and revenue from the real estate investments he had made in his prime, he managed to get back on television. Then he built a television network of his own. With hard work, he was able to secure residual income from the moment he left the stage in 1988 to the present. Book by book, volume by volume, he wrote a complete commentary on the Bible stretching over five thousand pages. On top of the money his ministry was able to invest, he also had a full printing press and recording studio built on the ministry’s campus. He returned to the studio to record another dozen albums, to produce as many with other singers under his label, and with industry and patience, he quietly became one of the wealthiest ministers in America. He even managed to publish a new version of the Bible, one that placed his red-lettered notes beside those of God, the prophets, and Jesus. While some saw him as the exemplar of Evangelical self-martyrdom, others saw a shark who was always moving to stay alive.

Despite his continued success, however, he remains the punchline to off-color jokes, his name defined by the lowest point of his life. Lampooned, misunderstood, antagonized, and intentionally provocative, his life and ministry remains a pattern for Evangelical ministers aspiring to the fame that he embodied.

As a child, I first learned about Swaggart from my mother. I knew him from the periphery of childhood, a voice on the radio and on cassettes, a blurred image on the television where he was framed like a Caravaggio painting. And then, suddenly, he was the silence between my parents. Like the painful loss of a relative whose name was not to be spoken anymore, he became a question suppressed and denied inside our family.

The summer after Swaggart’s admission of guilt, my mother returned from a missionary trip. She had sweated all summer, leading a team to build a school for orphans. There were rumors at the start of the summer, but she pushed them aside. She wanted to believe the best, to believe that the rumors were untrue. More chatter than substance. She could not help but notice, however, that her team that summer was rowdier, showing considerably less focus on their task. They were disillusioned and disinterested in the work. The hosts of the project were local missionaries who were already experiencing financial strain as the spigots of support turned off. She chose not to make the connection at the time. Instead, she willed all of this away, continuing to believe that the rumors weren’t true. The stories her team members gleaned from phone calls home were just more rumors. She flicked them away, choosing still not to give them attention or weight.

When she returned, my father caught her up on what she had missed. It was true. Swaggart had “fallen” and Evangelicals like my parents were the punchline right alongside with the famed minister. Evangelicals were gullible rubes in the headlines, on the late-night circuit, the punchline in stand-up specials. How could they be so stupid? How could they miss the tell-tale signs? Swaggart was a sweaty spectacle. No one was surprised that his ministry fell apart in the parking lot of a by-the-hour motel in the back corner of New Orleans; photos emerged of him in a tracksuit, bandana on, emerging from a room with a prostitute. When the prostitute gave interviews, it only compounded the severity of Swaggart’s fall from grace. He was a germophobe and didn’t want to touch her or have her touch him. He only wanted to watch. He wanted to know about the woman’s young daughter. He wanted to save their souls, to bring them to one of his crusades. He wanted photos of the little girl and kept asking for them. He always begged for a lower fee. And he never tipped.

My mother brought a simmering frustration back home with her. Swaggart’s fall had affected the world, the ripples felt by missionaries as far away as Switzerland and Papua New Guinea, in Guatemala and Egypt, Russia, and Tunisia. The entire world, everywhere Swaggart’s television and radio programs aired, had heard the rumors coming out of the headquarters of the Assemblies of God in Springfield, Missouri. Something more was happening, however. Something was shifting and this shift, whatever it would become, was happening too quickly to properly name or identify it. My parents own divorce was in the making now, only they would not be able to name that for another two years. The collapse of Swaggart’s ministry shuttered schools and churches; it had exposed Evangelicalism as hypocritical and too late in apologizing for that hypocrisy. The curtains of entertainment pulled back, and Evangelicalism was revealed as an extension of colonialism, white supremacy, riddled with immorality and corruption. At the local level, churches were divided between forgiveness and justice. In the home, husbands and wives began to explore the limits of what it meant to forgive adultery, if prostitutes “counted” or even mattered. The role of women in the church. The need to protect their children from predators, not just lecherously unshaved perverts in vans, but now well-dressed ministers also. The decay of Evangelicalism had become rot and surgery was needed if it was to survive into the Nineties.

Throughout that next decade, my parents now divorced, my mother managed to keep a copy of the evangelist’s biography in her collection of books. On the cover, a plump and youthful Swaggart in a white leisure suit is self-assured, smiling, looking into the distance, in his prime with the glory of God before him stretching forward and forward into eternal glory. It is a remarkable contrast when juxtaposed with his 1984 hymnal, Heaven’s Jubilee. There he is sitting cross-legged, staring angrily away from the camera; the covers of the albums released after his fall are poorly lit, unnatural. Swaggart either stares directly into the lens with a threat of menace about him, or he has his back turned, looking away and contemplating his failures.

Bored one weekend in 1995, I consumed the biography while watching my little brother. I only half-believed what Swaggart, or rather his ghostwriter Robert Paul Lamb, had written. Many of the claims Swaggart made were remarkable for their strangeness. When his car broke down during an early ministry effort, Swaggart “anointed” his car and it began working. His sibling rivalry with cousin Jerry Lee Lewis prevails throughout multiple stories, bordering on resentment, particularly early in Swaggart’s ministry when Lewis was at the zenith of fame. Others were broad, undefined, and unverifiable, a trait that would continue throughout his ministry. The broken car anointing? Swaggart was the only witness to the car miraculously “reviving” from “death.” The prophecies about Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Witnessed by church members, but vague enough to mean almost anything. It is entirely subjective whether the “prophecies” of a young boy came to pass in the way he interpreted them.

Such general, sweeping claims came to define his ministry. At times, Swaggart admitted that his vagueness about the future was his own fault, evidence that God spoke to him, just not the specifics. After all, the biblical prophets lacked specificity. Jimmy – the boy as well as the man he would grow into – was following their example. The prophets saw heralds “like a man” and “like” recognizable animals. Later interpreters claimed this was evidence of tanks in World War II, helicopters in Vietnam, and the Gulf War. Everyone knew the prophets, living in an ancient period, would not understand or have language for jets, missiles, or be able to rightly name the nations for later readers. Gag and Magog, in the Bible, became Germany and Russia. Then the Soviet Union. Then Russia again. The lack of detail allows for many interpretations, and rather than evidence of a flaw in the prophecy itself, the lack of detail becomes a dividing line for the Elect, who can rightly understand the Bible, and everyone else who God laughs at in their confusion. The Pope becomes the Whore of Babylon and the beast she rides on. And then another false religion able to deceive the nations. Swaggart borrows from these interpretations, originating with the Scofield Bible (1909), then replicated in the Dakes Bible (1963), popular among Pentecostals.

For Swaggart, facts did not matter so much as the story he was trying to tell. It doesn’t matter whether the Pope is the Antichrist, the Whore of Babylon, or the Beast of Babylon. What matters is that the Pope preaches a false doctrine. In sermons, timeless events always happen “a few weeks ago.” Misfortunes he read in the newspaper “happened to a friend of mine, the dear brother” or occasionally, “dear sister.” His softened details do not stop there. In his 2011 book, Paul the Apostle, Swaggart tells a story about a former president of Yale University who admitted to a donor “We do not know how Western Civilization began.” Framing himself and his interpretation of Paul, Swaggart fills the vacuum of knowledge that even the head of a world-renown university was unable to produce. “If the President of Yale had known the Bible,” Swaggart explains, “He would have had some understanding as it regards this subject. The truth is, the Source of Western Civilization is the Lord Jesus Christ, with all that He has given to us, made possible by the Cross of Christ. But the human instrumentation used by our Lord was Paul, the Apostle.” Conveniently, Swaggart goes on to claim that he and the “revelation” given to him by God have the same eternal power to define Western Civilization for the next thousand years as the Apostle Paul. It is a grand claim, consistent with the fabulation that has defined many of the other stories he tells about himself and his ministry.

His alleged story about the former President of Yale is not unique. Evangelicals have long held an admiration for scholarship, even while denigrating education and actively dismantling it where possible. As Mark A. Noll writes in The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind,

“As documented for many years by many scholars, journalists, pundits, reporters, and bloggers, when the American population is divided into constituencies defined by religion, “white evangelicals” invariably show up on the extreme end of whatever question is being asked.

“These evangelicals have been least likely to seek vaccination against the coronavirus, least likely to believe that evolutionary science actually describes the development of species, and least likely to believe that the planet is really warming up because of human activity. White evangelicals are also most likely to repudiate the conclusion of impartial observers and claim that the 2020 presidential election was “stolen.” They are most likely to regard their political opponents as hell-bent on destroying America. They are least likely to think that racial discrimination continues as a systemic American problem. And in response to a question that is usually formulated poorly, they are most likely to believe that Scripture should be interpreted “literally.”

“In each of these spheres, white evangelicals appear as the group most easily captive to conspiratorial nonsense, in greatest panic about their political opponents, or as most aggressively anti-intellectual. Yet for each, examples from the past, but also the present, indicate that an entirely different stance is possible. Even more pointedly, convictions foundational to Christianity can demonstrate that these attitudes betray the faith evangelicals claim to follow.”

Mark Noll, The Scandall of the Evangelical Mind (2022)

It was not just distant snobs in their Ivory Towers. As his ministry grew, Jimmy would often refer to those closer to home, ministers who he had met during his years of ministry. Within his denomination, the Assemblies of God, Jimmy would often attend conferences and speaking engagements, privately targeting fellow ministers as rivals for the thin profit margin to be made in circuit preaching. Other ministries were led by “limp-wristed” pastors and “milquetoast” preachers. Ministers who aspired to the talent Swaggart showcased on the stage were “pretty pompadoured losers filled with sinful rot, pardon me for being so blunt.” Details were softened, to avoid difficult conversations or denominational discipline, though Swaggart insinuated from his radio and emerging television ministry that he knew more than he let on. He knew more than he let on and what he knew wasn’t hearsay, but what he heard God say.

Of course, the rumors he spun were always baptized. Talebearing and gossip were sins, so while the targets of Jimmy’s anger may have tried to hide from their congregations back home, their failings were curiously revealed to him in prayer. God, you see, was Jimmy Swaggart’s best friend and the feeling was mutual. God shared things with Jimmy because he could be trusted both to cover them up as well as to administer justice, when necessary. Exposing sins, “revealing” them to Jimmy, was normal and occurred frequently between the two best friends. God had found a friend in Jimmy one who He could trust to share His own frustrations. God revealed things to Jimmy’s wife Frances also, things the couple could file away for an opportune moment, to insulate them. No one could understand this all, no one except Jimmy Swaggart.

In hindsight, it seems Jimmy could have been talking about himself whenever he spoke out against others. As I read Lamb’s biography of him, I was struck by the way Swaggart was depicted as an inevitable next step in the activity of God on Earth. He was above sin, able to judge it because it no longer affected him. The biographer insisted that the minister was the real deal, genuine and consistent. Even as a child reading the biography, I could not help but wonder which was more scary, that Swaggart was what his critics claimed – a liar and a fraud, prone to theatrics and storytelling to win the cheap seats – or that he was in fact telling the truth all along.

It was hard to know the difference. Who could tell, given his theatrics? Caricatured, Swaggart would strut the stage, pace it from one side to the other until he would jerk and twitch like a chained animal at the end of the leash. He would sweat profusely, eyes bulging so that he could see the sins of everyone under his gaze, chin jutting self-righteously. He would erupt into laughter and, without even catching his breath, roar with anger at nameless and faceless sinners like the ones who attended his meetings. He was on a mission from God, restrained only by “the Master.” In his “Crusades” around America and, eventually, around the world, he always seemed to be looking out past the crowds into the distance with fury counterpoised to the sweet, soft gaze on the cover of the book. Both, in the end, appeared consistent with one another. Swaggart has remained popular within Evangelicalism because, by all appearances, both sides of the story have been true. He was quick to agree with his critics, with the comedians who mocked him. Yes. Yes, indeed. He was a flawed individual. He admitted as much. But he was also God’s best friend, on a mission to save the entire world.

Cont. in Chapter 1